- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why sandalwood farming is losing its essence

A few months after sandalwood smuggler Veerappan’s long reign of terror ended in 2004 with his killing in a police encounter, Chinnalu Chinnegowda began his tryst with the trees famous for their fragrance. Unlike Veerappan, however, Chinnegowda was on the right side of the law. The farmer from Kiragavalu village in the old Mysore region purchased 225 acres of land in an area where...

A few months after sandalwood smuggler Veerappan’s long reign of terror ended in 2004 with his killing in a police encounter, Chinnalu Chinnegowda began his tryst with the trees famous for their fragrance. Unlike Veerappan, however, Chinnegowda was on the right side of the law.

The farmer from Kiragavalu village in the old Mysore region purchased 225 acres of land in an area where Veerappan had great control in his heydays. The uncultivated rain-fed land in the erstwhile sandalwood-rich region of Kollegal cost Chinnegowda close to ₹2 crore in 2005.

Until 2005, Chinnegowda, then an aspiring politician, had no clue about mass cultivation of sandalwood. He only used it in small amounts for religious purposes and knew it had a great commercial value. But egged on by a friend, Chinnegowda saw a hope in making money through sandalwood farming, especially after the state government changed rules in 2003 to allow private individuals to own sandalwood trees.

Chinnegowda planted about 3,000 sandalwood trees, a highly-endemic species, in about 100 acres of land in 2005-06. Depending on 11 borewells and two open wells, he cultivated banana, pomegranate and lime in the rest of the land. To his advantage, in 2012 the Kabini dam water reached his farm through the canals. Despite all that, Chinnegowda dreams are far from coming true anytime soon.

Scent of a bygone era

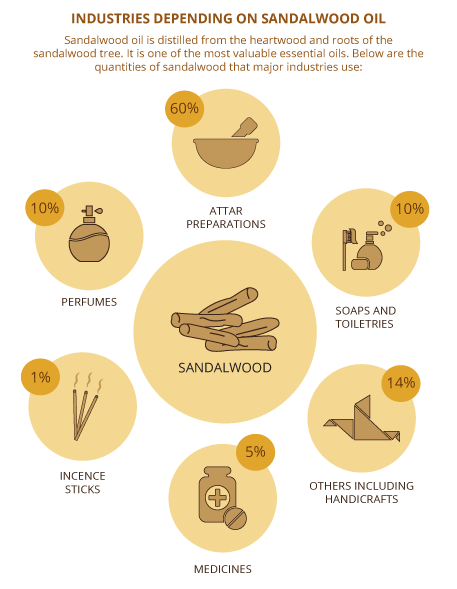

Santalum Ablum or Indian sandalwood is a tropical tree that grows 10-20 feet high and is a source of fragrance. Its oil extract is used in attar industry, perfumery, soaps and toiletries, scented tobacco and pan masala, healthcare and wellness industry (to treat skin diseases, aroma therapy, acne, stress, anxiety etc.). The rich history of sandalwood cultivation dates back to Tipu Sultan’s era. The 18th century Mysore king declared sandalwood as a royal tree and took over its trade on a monopoly basis around 1792 to fight the British. This practice was continued by the Maharajas of Mysore, and subsequently by the Karnataka government until 2000s.

Until 2001-2002, sandalwood trees in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, which accounts for more than 80 per cent of the sandalwood production in the country, were the property of the state government, regardless of where they grew. But in 2003, the two states ‘liberalised’ sandalwood cultivation and trade by amending the Forest Act and Rules wherein it said sandalwood trees can be owned by planters, but can be sold only to the state forest department.

Ever since, farmers like Chinnegowda have shown interest in cultivating sandalwood on a commercial scale. Besides, the state-owned Karnataka Soaps and Detergents Ltd (KS&DL), maker of the legendary Mysore Sandal Soap which also controls the sandalwood oil factory in Mysore, started a campaign that involved the company entering into agreements with farmers with buyback options.

But all that didn’t necessarily mean sandalwood farmers could make big money.

High risk and cost of maintenance

Very few farmers can afford to invest in sandalwood cultivation, considering the regulatory challenges of selling the wood/oil, apart from the fear of theft as it is valued high in the market. What adds to their woes is a ban on its export besides waiting for almost 20 years for a tree to mature in order to get good oil content.

Farmers end up spending most of their money on securing the farm and maintaining it. For instance, Chinnegowda has three dogs, two caretakers, CCTV cameras (recently damaged by miscreants), and solar-powered electric fence surrounding his farm. He has now sought the help of the forest department to provide security.

For Doddamage Rangaswamy, a farmer in Hassan district, keeping the thieves at bay meant spending in ingenious technology. Rangaswamy was forced to insert microchips in some of his trees (that were ready to be cut) in the hope that he could trace them if robbed or smuggled.

In Chintamani, a town about 70 km from Bengaluru, Ramesh could not afford to provide high-tech security to his farm and lost a few trees to thieves on a single night.

In response to a question in the Lok Sabha, Jayant Sinha, former minister of state in the ministry of finance, said the customs department had seized 43.01 metric tonnes of sandalwood worth ₹8.17 crore between 2011 and 2015.

Besides, many farmers complain that the government is not procuring sandalwood from them despite several requests made to the forest department.

“We run from pillar to post to convince the department officials to permit us to cut the trees. What is the point of waiting for 12-15 years for the trees to mature when you are not able to reap enough benefits,” asks a disillusioned Ramesh.

According to former deputy general manager of Karnataka KS&DL, VS Venkatesh Gowda, the state government is ignoring the local farmers and instead gets wood from Kerala and is even planning to import Australian oil for its own soaps and detergent units.

Experts believe that smuggled goods from Karnataka and Tamil Nadu reach Kerala and Uttar Pradesh, which in turn are sold at a cheaper price in these states.

In 2006, the Supreme Court cracked down on unlicensed sandalwood oil-manufacturing factories and directed Kerala to shut down as many as 24 units.

“Farmers get no subsidies, no post-production help or guidance and no incentive for cultivating a rare species of plant. To add to all that, a corrupt mechanism of approval to cut trees further discourages them,” says Gowda.

A farmer, he goes on to add, ends up spending 15 per cent of the total cost on securing his farm.

The current managing director of KS&DL, MR Ravi Kumar, however, declined to comment for the story.

Another factor that weighs down farmers like Ramesh and Rangaswamy is the private distillation process. “Considering the price that sandalwood and its oil fetches in the market, some farmers do resort to private distillation process even though it is illegal,” says a scented incense stick manufacturer from Mysore. He, however, didn’t wish to be named.

That way they completely bypass the government procurement route used in the domestic perfume and incense stick industry. Also, the sandalwood produced in parts of Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan is cheaper by a third as spurious items mixed with synthetic compounds are available without much restrictions, he adds.

Patience pays but how

Small farmers who depend only on their farms for daily needs are often unable to reap the actual benefits of large-scale sandalwood cultivation. However, big farmers who are into multi-cropping and have the money to secure their farm and wait for 15-20 years do get good returns.

For instance, at Chinnegowda’s farm, Dr HS Anantha Padmanabha, who tested the oil content in front of this reporter, says the oil and wood from each tree could fetch about ₹3.2 lakh. According to Padmanabha, a former senior scientist at the Institute of Wood Science and Technology, one tonne of sandalwood can produce 50 litres of oil.

Going by this estimate, Chinnegowda, who claims to have spent about ₹15 crore in the past 13 years in procuring land and maintaining the plantation, could earn as much ₹90 crore (that’s six times the money he has spent over the years). Besides, he can make money from the host/supporting plants as well that the sandalwood trees grow along with.

Fading fragrance

Despite the good prospects, Chinnegowda is not entirely happy. “Karnataka, once famous as the land of sandalwood, has lost its charm with over exploitation, smuggling and forest fire,” he says.

“I wanted to bring back the lost tradition. Today, sandalwood and its by-products are accessed only by rich people. But once the supply increases, the cost will come down and will be available to all.”

Experts agree with Chinnegowda that the average production of sandalwood has fallen drastically. In the past five decades, they claim, it has come down by more than 90 per cent.

“The average sandalwood production in India in 1965 was about 4,000 tonnes. The production declined to about 1,000 tonnes of wood in 2005 and further dropped to mere 300 tonnes by 2014,” says Padmanabha.

“Smuggling wasn’t the only reason. Sandalwood oil factories of the state too exploited the forest resources. Most of the elite population of the species disappeared from the natural forest, thus reducing the regeneration potential.”

While farmers in Karnataka have the option of selling it either to the government (forest department) or the sandalwood oil factories or the Karnataka Soaps and Detergent Ltd, their counterparts in Tamil Nadu can’t sell it to anyone else but the the government. Also, both import and export of sandalwood are banned.

Mariappan D, a retired forest range officer, says farmers in Tamil Nadu aren’t usually enthusiastic about planting sandalwood as they fear the regulatory challenges will hurt their business. “We have extreme drought conditions. Moreover, there’s no guidance and buyback option from the government of Tamil Nadu. So why would farmers prefer sandalwood cultivation?” asks Mariappan.

India was once a major producer of sandalwood and its oil. While its contribution to the world market was estimated to be at 80 per cent in the early 1990s, Indonesia and Sri Lanka contributed another 10-12 per cent. But over the years, Australia has picked up its production, particularly of the India varieties. Experts, however, believe the oil content in sandalwood grown in India is richer compared to the Indian varieties nurtured in Australia.

In the 1960s, Indian Sandalwood (a good variety) was auctioned at ₹6,800 per metric tonne. It increased to about ₹21 lakh in 2005. Now it costs anywhere between ₹1.1 crore and ₹1.25 crore per metric tonne. A recent e-auction in 2016 in Karnataka fetched ₹1.25 crore, a 15 per cent rise in one year. Similarly, the price of one kilogram of oil now costs about ₹2.5 lakh. In the government-owned Cauvery Handicrafts, the oil costs ₹12,334 for 25 gm (about 4.93 lakh for a kg).

Experts say it is simply a matter of demand and supply. Today there’s a higher demand for Australian sandalwood oil even if the oil content is less.

“Who would pay ₹2.5 lakh per kg for the Indian sandalwood oil when the same oil from Australia cost ₹1 lakh. Also, people often can’t differentiate between pure and impure substances. So the markets are full of spurious items,” says Ashwani Mahajan, a sandalwood oil dealer and perfume exporter.

Synthetic substance mixed with sandalwood oil are available from China and even Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. “So, it has become easier to con people,” says Mahajan.

Until the situation changes in favour of sandalwood farmers, people like Chinnegowda and Rangaswamy can only wait and watch their trees grow.