- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why Kashmir can’t decide what to make of Sheikh Abdullah’s legacy

For many months before he passed away, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah remained critically ill. During those months of agony for his family, friends and followers, rumours of his death floated from time to time. Each time anyone said Abdullah had passed away, followers of the leader would beat up the person. Hours before Abdullah actually died in September 1982, rumours about his demise once...

For many months before he passed away, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah remained critically ill. During those months of agony for his family, friends and followers, rumours of his death floated from time to time. Each time anyone said Abdullah had passed away, followers of the leader would beat up the person. Hours before Abdullah actually died in September 1982, rumours about his demise once again spread across J&K. Hundreds of lambs were sacrificed in the Valley in a belief that the sacrifices would prevent the inevitable.

Once the news was confirmed, gloom descended on the Valley with markets closing down and traffic coming to a halt.

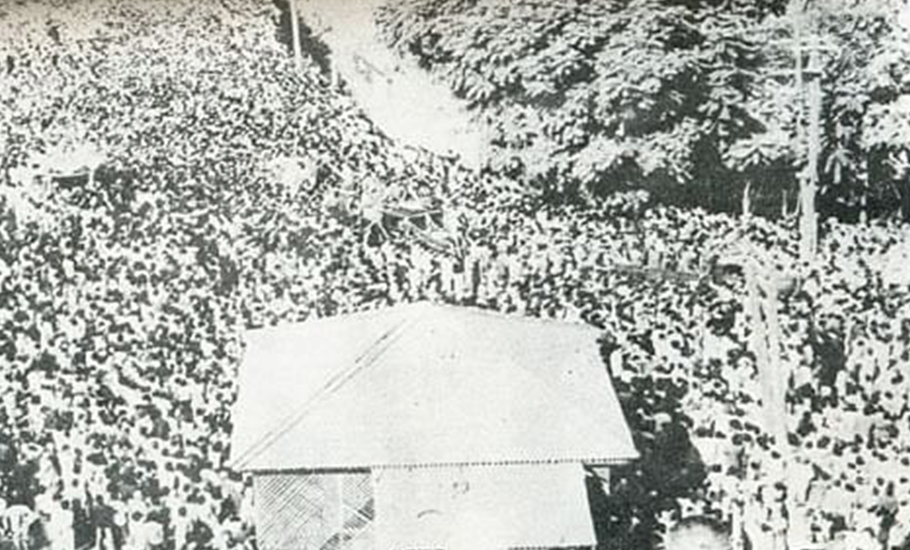

At the Polo Ground in Srinagar, where the leader’s body was kept for the public to pay their homage, his followers wailed and wept inconsolably.

Wrapped in the national flag, Abdullah’s funeral procession took over eight hours to cover a distance of around 10 km as nearly one million mourners gathered to bid their last goodbyes. In a stampede that followed, four mourners died and many got injured.

Cut to 2021, Sheikh Abdullah’s burial chamber in Hazratbal Dargah has been given a 24*7 security vigil for fear that the mausoleum could be vandalised by angry Kashmiri protesters.

Thirty-nine years after his demise, Abdullah’s political legacy in Kashmir stands highly contested with fans and detractors divided right down the middle over what he stood for and what he achieved for Kashmir. The debate over the Sheikh’s political career was rekindled on the late politician’s 116th birth anniversary on December 5.

Expectedly, the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference (JKNC) leadership paid floral tributes to the late Abdullah while the detractors held him responsible for the region’s current mess and political uncertainty.

“He [Sheikh Abdullah] was a popular leader and a social reformer who fought for the rights of the oppressed sections of the society… As an inspiring political icon, he symbolised the aspirations of the Kashmiri people as no single individual could have ever dreamt of doing,” the JKNC said in an official statement referring to Abdullah as a “man of iron determination” and “incisive vision”.

The rise

Abdullah’s fans describe him as ‘Sher-e-Kashmir’ (Lion of Kashmir) and credit him for playing a role in the political awakening of the people of J&K since the 1930s, for launching the ‘Quit Kashmir’ movement in the 1940s, and also for introducing the land to tiller reforms at a later stage.

Some political commentators do shower accolades on him for rechristening the Muslim Conference — the region’s first political formation in 1931— as the National Conference in 1938-39 with the aim to put a stamp of approval over his ‘secular’ credentials. But critics interpret the move as the ‘original sin’ committed by Abdullah much to the detriment of J&K’s majority (Muslim) community.

Who was Sheikh Abdullah? Why is his legacy disputed and so hotly contested?

Born on December 5, 1905, in the Soura locality on the outskirts of Srinagar city, Abdullah rose to prominence once he returned to the Valley with a master’s degree in Chemistry from the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). He began his career as a teacher but soon took a plunge into politics.

An incident of alleged sacrilege of the Quran in Jammu prompted the senior Abdullah to actively participate in the region’s politics. He delivered a rousing speech before an estimated crowd of 30,000 people condemning the act going on to say that “the Muslims [of Kashmir] must fight for their birth right.” The speech turned Abdullah into an instant hero.

Within no time he emerged as one of the best crowdpullers. His fiery speeches would attract mass gatherings in Kashmir. He would recite the Quranic verses melodiously winning both social sanctity and political relevance among the majority community.

The troubles

On August 9, 1953, Abdullah was unceremoniously dismissed as Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir and thrown into prison by Indian Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru — until then his close friend. Abdullah was imprisoned on charges of sedition.

Bhola Nath Mullik, then director Intelligence Bureau (IB), and a spymaster considered to be a close confidant of Nehru, wrote in My Years With Nehru that it took five years from Abdullah’s arrest in 1953 for charges of sedition to be laid against him, and another four years before they were brought before a court, where “witnesses showed signs of wavering”, while “some of our most sensitive agents had been exposed and it was difficult even to keep them safe in the valley…”

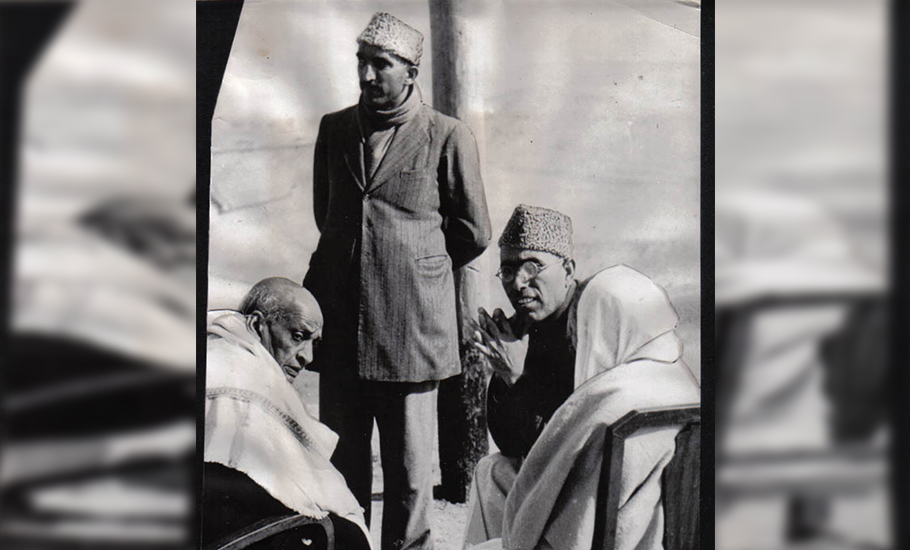

Sheikh Abdullah: The ups and downs of life

Sheikh Abdullah: The ups and downs of life

Jammu-based commentator, author and peace activist Balraj Puri had pleaded with Nehru not to put Abdullah in jail, but the response from Nehru was not heartening. “We have gambled at the international stage on Kashmir, and we cannot afford to lose. At the moment, we are there (in J&K) at the point of a bayonet. Till things improve, democracy and morality can wait.”

In Kashmir: Towards Insurgency, Puri noted: “Nehru warned me against being too idealistic and asserted that the national interest was more important than democracy.”

Some are of the view that, secretly, Abdullah was a “closet sympathiser of Pakistan” while others have no doubt that the Kashmiri politician was committed and “totally aligned to India”. Without a shadow of a doubt, Abdullah’s personality was complex and multi-layered.

In January 1949, Abdullah, in an interview with foreign correspondents Michael Davidson and Ward Price, had envisaged “an independent Kashmir as an Asian Switzerland”. Some believe that the interview in which Abdullah spoke of “an independent Kashmir” became one of the main reasons why his personal relationship with Nehru, otherwise his bosom friend, fell apart, and eventually led to his arrest and dismissal from office in 1953.

Sheikh Abdullah served both as prime minister and chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir at various stages and spent over two decades in prisons in separate stints. His fallout with Nehru and the subsequent jail term is said to have broken his spirits. In part, he resigned to fate and succumbed to the changing regional contours and geopolitics.

The compromise

To secure his return to politics after an 11-year-long incarceration (1953-1964), it is said, he caved in and signed an accord with then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1974-75. The agreement restated the conditions of Jammu and Kashmir’s incorporation into India since 1953 with a clause that the state’s administration would be maintained under Article 370.

This was a huge climbdown for Abdullah who had spearheaded a movement for a United Nations-mandated referendum in J&K under the banner of the Plebiscite Front (Mahaz-e-Rai Shumari). Many saw this as Abdullah’s political treachery.

It is another matter that he described his political struggle as “siyasi awaragardi” (political wilderness/meandering).

According to Ather Zia, a Kashmiri anthropologist and writer based in the United States, “In the 1940s, Sheikh Abdullah was seen as an unrelenting figure of Kashmiri nationalism.”

Zia co-edited a book titled A Desolation Called Peace: Voices from Kashmir along with another academic and author, Javaid Iqbal Bhat.

“His [Abdullah’s] political missions ranged from spearheading the Quit Kashmir movement against the Dogra warlords to forming the Plebiscite Front to demand the right to self-determination for Kashmiris,” the duo recorded in the book, adding, “His increasing acquiescence to Indian policies cost him the carte blanche that the Kashmiri masses had granted him.”

Once a towering political figure on Kashmir’s political landscape, who commanded respect from a large section of the masses, many now hold Abdullah singularly responsible for the current mess. They accuse the leader of lacking political foresight and making avoidable compromises, one after another in 1947 and in 1975, to put his self-interest and political career ahead of peoples’ aspirations.

In The Indian Ideology, Perry Anderson noted, “In power, Abdullah’s main achievement had been an agrarian reform (land to tiller) putting Congress’s record of inaction on the land to shame.”

However, in Anderson’s view, once Abdullah was “restored to office and obedience in the seventies” [when Sheikh Abdullah signed the accord with Indira Gandhi] he proved “ultimately as disastrous for his people as any Abbas” and “passed a franchise for compliant enrichment to his offspring, who handed it on to his offspring, now a crony of the Nehru greatgrandson.”

What he ignited

When the British colonial power in South Asia was at its peak, Kashmir’s political landscape was dicey with the power balance shifting from one dynasty to the next. In 1846, the British rulers sold the picturesque Kashmir Valley along with its provinces to the Dogra warlord Gulab Singh for a sum of 7,50,000 Nanak Shahi rupees. The most significant and memorable agitation against the Dogra rule in J&K took place in July 1931.

Prosecution of Abdul Qadeer Khan, one of the leaders at the time, instigated mass protest demonstrations against a set of unjust laws introduced by the Dogra Maharaja, Hari Singh.

On July 13, 1931, the Dogra forces opened fire on peaceful protesters leaving 22 Kashmiris dead. Sheikh Abdullah was 26-year-old at the time and beginning to make a mark as a politician.

“There is little doubt that he [Sheikh Abdullah] ignited something–a pent up nationalism–in Kashmir between 1931 and 1942,” said professor Siddiq Wahid, a noted academic and former vice-chancellor of the south Kashmir-based Islamic University of Science and Technology (IUST).

“But his legacy apropos of the Jammu and Kashmir state needed a more nuanced understanding of history, culture and interstate relations. It is debatable whether this is an ahistorical expectation, but we certainly need to abandon the facile criticism of his role and place in the state’s or, today, the region’s history,” Wahid told The Federal.

The late Shamim Ahmed Shameem, a journalist and parliamentarian from Kashmir, had once said about Abdullah: “Unn se hamari subah bhi ibarat hai aur shaam bhi” (To him we owe our sunrise as well as the sunset.”

Those against whom his mausoleum now needs to be guarded challenge the encomiums heaped on Abdullah as they take a hard look back at what brought Kashmir and Kashmiris to where they stand today.