- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

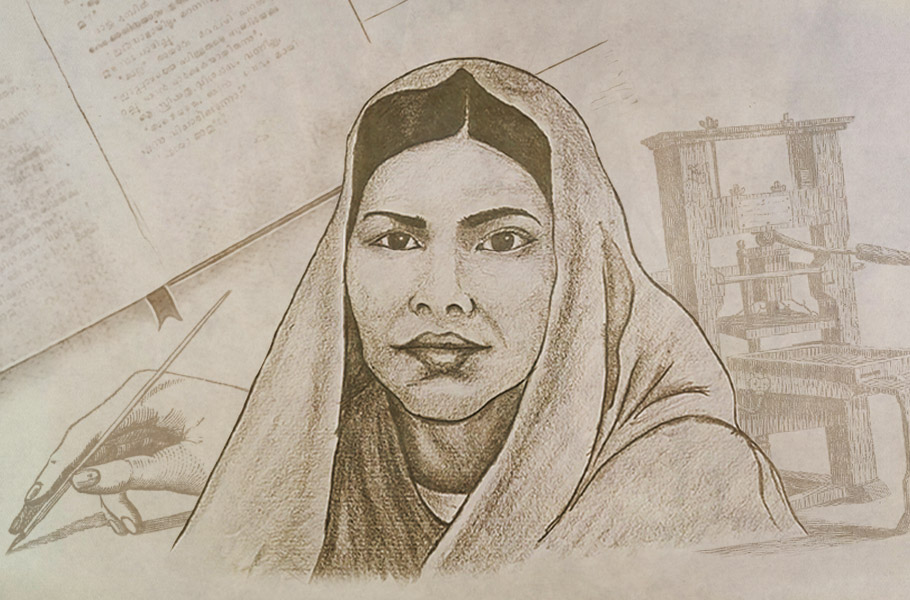

Why it took Kerala so long to recognise the work of a woman editor of 1930s

Haleema Beevi, the first woman editor of Kerala, played multiple roles with a single objective—to empower, educate and organise Muslim women.

“Dear sisters, let’s not hesitate to send your daughters to schools. Prophet Mohammed never treated women inferior to men. We have to unite and demand our educational and employment rights. I hope you know that only the crying baby gets the milk. In our times, even crying babies do not get milk. Hence we have to keep on crying. Those who are educated among us should make use of...

“Dear sisters, let’s not hesitate to send your daughters to schools. Prophet Mohammed never treated women inferior to men. We have to unite and demand our educational and employment rights. I hope you know that only the crying baby gets the milk. In our times, even crying babies do not get milk. Hence we have to keep on crying. Those who are educated among us should make use of every opportunity to get employment. We also have the duty to serve the nation. Women should take up employment. That only helps them to uphold their self-esteem.”

The above speech by a feisty 20-year-old Haleema Beevi, at the Muslim women’s conference held in Kerala’s Thiruvalla in 1938, went on to launch many a small and big revolutions for women’s emancipation. The text of this speech was published in the July 1938 issue of ‘Muslim Vanitha’, the first magazine launched by Haleema herself.

Haleema played multiple roles with a single objective—to empower, educate and organise Muslim women.

But nearly a century later, there is little mention of her in the annals of history. This, despite Haleema being a pioneer in the journalism industry. She was the editor of four magazines and a newspaper, a first for a Muslim woman in Malayalam language. She almost single-handedly fought for the rights of Muslim women. She was the first Muslim woman to be elected a municipal councillor. But she perhaps received the least recognition for the fact that she nurtured many legendary Malayalam writers like Vaikkom Muhammad Basheer, Changambuzha Krishna Pillai and Balamani Amma.

Haleema was born in Adoor, Pathanamthitta, in 1918. When her father passed away, Haleema was quite young. Her mother, Maitheen Beevi, had to raise seven children all by herself. Yet she was deeply passionate about modern education and insisted on her daughters too having a taste of it. She sent Haleema and her elder sister to school, ignoring resistance from many quarters.

Against all odds, Haleema did her schooling till Class 7, which in itself was a rarity back then. Muslim girls being sent to school was not common in those days. The maximum exposure given to them was religious education through madrassas.

As a student , she was inspired by the activities of NSS (Nair Service Society) which organised multiple programmes for promoting the education of Nair girls. She could not attend the meetings but was passionately interested in knowing the deliberations and watched meetings from outside. She also learnt how to organise women from here.

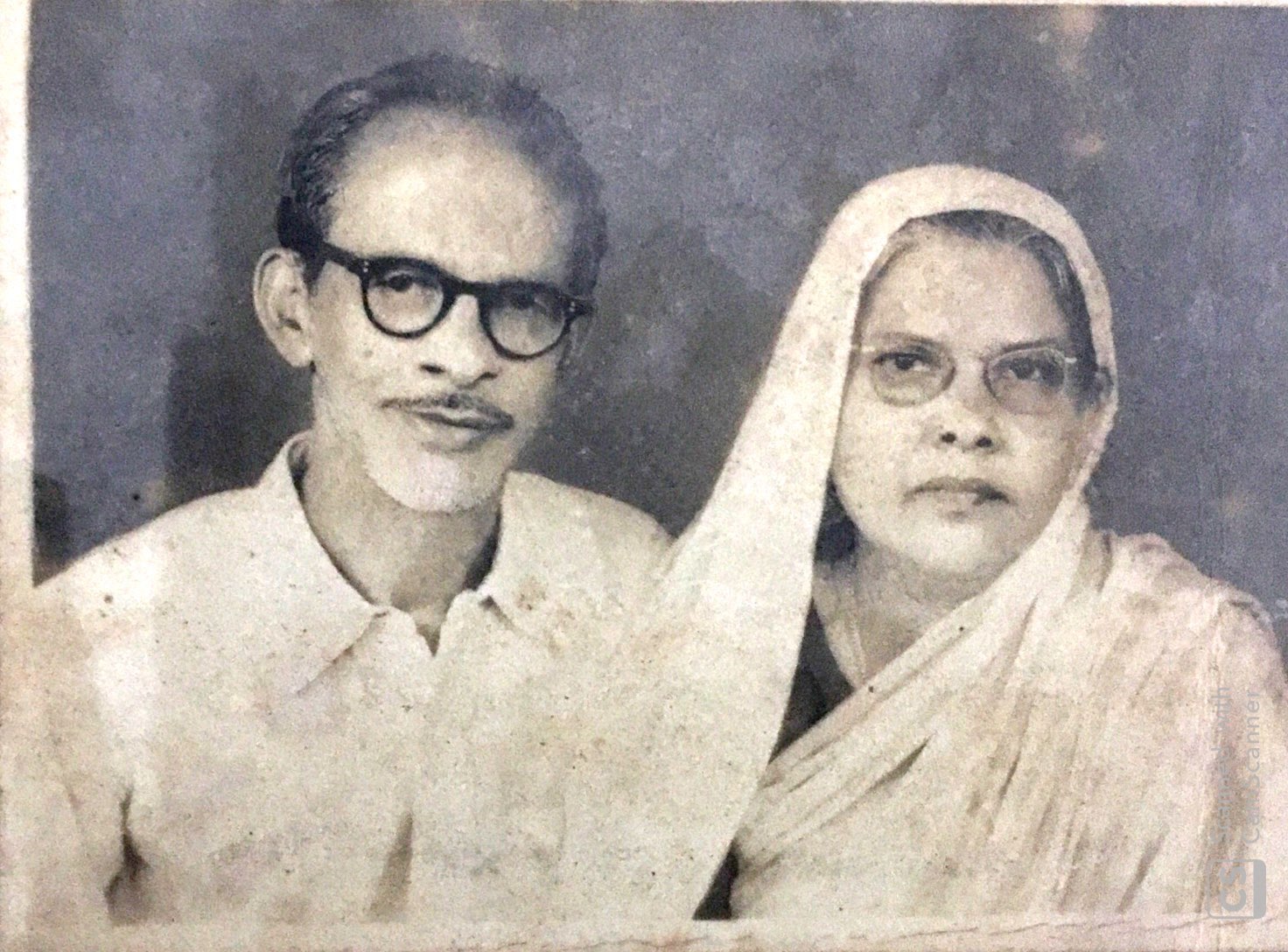

At the age of 17, Haleema Beevi was married to KM Muhammad Moulavi, a progressive activist and reformist. who stood for modern education and values of renaissance.

Haleema Beevi got tremendous support from her husband when she launched her first magazine ‘Muslim Vanitha’. It was a dream shared by Moulavi too.

Discovery of Haleema Beevi

Not much was known about Haleema Beevi till recently when two young writers, Noora and Noorjahan hailing from Malappuram district decided to dig up more about the mysterious editor ignored by writers of history (read men).

Their efforts bore fruit in the form of a book, aptly titled, ‘The Editor’.

“Every time we struggled to work on this book, we used to get amazed by the life lived by Haleema Beevi in such difficult times,” say the two writers in the prelude, explaining their difficult journey in discovering the late editor, printer and publisher.

Noora, a school teacher, is also a writer and poet, while Noorjahan is a PhD scholar at Tata Institute of Social Science (TISS) in Mumbai.

The book was recently published by ‘Bukkafe’, a publishing house at Kozhikode.

As an Editor and Publisher

When Haleema launched her first magazine, Muslim Vanitha in 1938, Travancore was rife with various social movements, including the freedom struggle and other social movements against the then Diwan CP Ramaswami Iyer.

And it was the first periodical in Malayalam that focused on the emancipation of Muslim women. Through the magazine, Haleema argued for the modern education, employment and civil rights of Muslim women.

However, her journey got difficult as she had to face stiff resistance from conservatives in the community.

“Muslim Vanitha was on the verge of closure due to financial crunch as it was not pampered by the powerful and conservative men in the community,” say Noora and Noorjahan.

Haleema Beevi had later in 1959 recalled the challenges she faced at Muslim Vanitha, in a special issue of ‘Almanar’ (in 1959), a monthly magazine published by Kerala Nadvathul Mujahideen which used to be a reformist organisation in Kerala.

“Six issues of the magazine had come out. By the time, the resistance against the magazine had become very ferocious. Muslim Vanitha took a strategic decision to keep away from religious controversies. We started a series on the life of Muslim women by the then known reformist EK Moulavi . Muslim Vanitha had profoundly influenced the Muslim women in Travancore , I have experienced those changes.”

Soon, Muslim Vanitha ceased to exist. Social and political pressures, the non-cooperation of distribution agents and financial crisis led to its early demise.

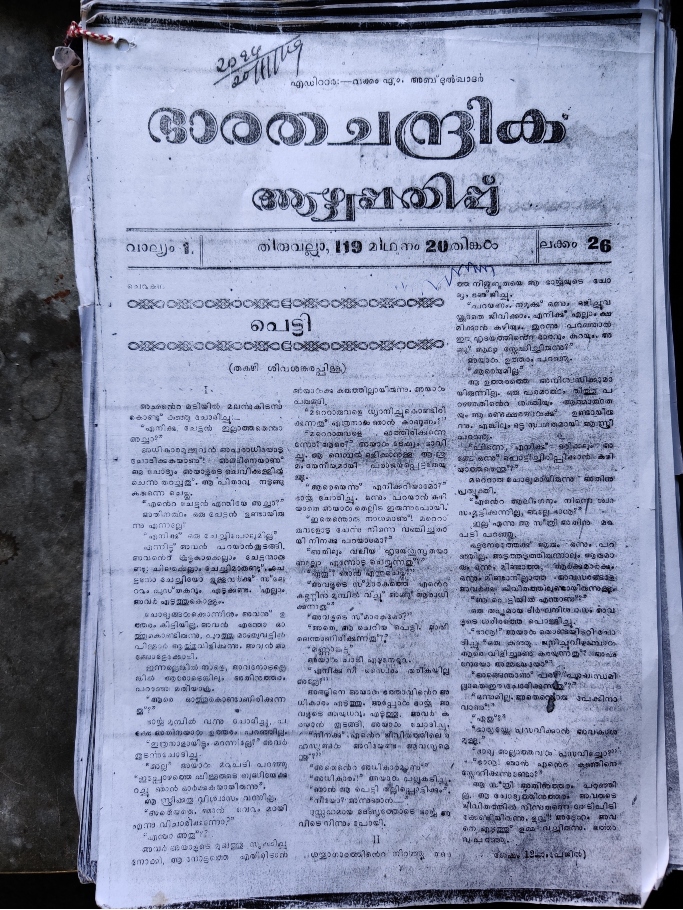

As a reformist and editor, Haleema could not bury her passion for publishing. She soon launched ‘Bharatha Chandirka’, a weekly magazine in 1944. This was more vibrant and diverse in content compared to Muslim Vanitha and went a step further by incorporating literature along with articles focusing on social change.

Bharatha Chandrika was printed from St Joseph Printing Press at Thiruvalla, issued every Monday, and was a platform for many later-legendary writers like Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, P Kesavadev, Balamani Amma and G Sankara Kurup.

Bharatha Chandrika also carried articles on the Second World War, the freedom struggle and the political position to be followed by the Indian Muslims in general. It also brought out various perspectives on the Partition.

But again, Haleema struggled for funds for the magazine. Ansar Beegum, second daughter of Haleema Beevi among seven children, shares her fragmented memories about her mother.

“Often the publishing fell into a deep crisis. She used to carry us with her and went house to house for fund collection on foot,” 84-year-old Ansar Beegum, a retired teacher living at Tirur in Malappuram district and who was also into social and political activism, tells The Federal.

“She (Haleema Beevi) went unnoticed by historians because of multiple marginalisation—one as a woman and the other as a Muslim,” says Noora.

The dream of converting Bharatha Chandrika into a daily newspaper was accomplished in 1948. Many progressive individuals extended a helping hand. Soon Bharatha Chandrika was relocated to Perumbavoor in Ernakulam district in 1949.

A well-wisher named Haneefa living in Singapore offered financial support by fundraising. Haleema sent her brother to Singapore who was successful in bringing Rs 700 from the fundraising venture, a huge amount back then.

Haleema bought a new printing press from Madras which was delivered to her through a railway parcel. However, the venture too hit an acute financial crisis and eventually led to its closure. The last printed copy of Bharatha Chandrika came out in 1952.

Along with Bharatha Chandrika, she ran another periodical named ‘Vanitha’ which was a continuation of Muslim Vanitha. Vanitha also was diverse in content with fiction, poetry, stories, world affairs, gender issues and family tips.

Haleema also used to write in other magazines and periodicals when her own journals ceased publication. Later in 1963, she came back to publishing by establishing Azad Memorial Press with her husband after selling their house and property.

Azad Memorial Press flourished with the printing of books and periodicals. Later in 1970, she once again took over the responsibility of editor by launching ‘Adhunika Vanitha’ (The Modern Woman), yet another women’s magazine.

By this time, Haleema Beevi had a team of women sharing a common dream of printing and publishing. Noora and Noorjahan found that there were other women like Philomina Kurian, KK Kamalakshi, Rahma Beegum, Saramma Kurian and BS Santhakumari in the editorial team.

Adhunika Vanitha provided a lot of space for young writers. The magazine conducted literary competitions and there were opinion pages to encourage young girls to write and express their views on current affairs. It also carried film reviews, health and beauty tips.

Again, financial constraints forced its shutdown after a year of publishing.

Activism and politics

Throughout her life, Haleema Beevi fought a fierce battle against conservative, anti-women ideas and practices among the Muslims. She strongly opposed Islamic clerics and leaders who propagated superstitions and archaic values that went against the civil and religious rights of women.

In an article in 1965, she recollects an incident. “A religious scholar from Malabar organised a lecture series in my locality. Thousands of people gathered to listen to his speeches. There were non-Muslims too who came to listen to his speech. He spoke against the modern education of women and supported the superstitions being practised in the community”.

She writes that she and a group of women boycotted the programme and walked out in protest. She also challenged the organisers that she would bring real scholars who know the true spirit of Islam. She managed to organise an alternate programme with speakers like KM Muhammad Moulavi and Aslam Moulavi who were reformists of those times.

Haleema organised conferences of Muslim women. The first of its kind was organised in Thiruvalla in 1938. In its opening speech, she strongly urged women to educate and organise and grab their rights.

“The community can never achieve progress if the women continue to be the weaker sex and remain poor in spirituality,” she said. (Muslim Vanitha, July1938).

She established the ‘Travancore Muslim Vanitha Samajam’ in 1938 and wanted to expand it to Malabar for which she travelled there and met leaders of women’s organisations of other communities. The organisation focused on sending Muslim girls to schools. They also established scholarships for girls for providing them financial support.

She continued organising massive women’s conferences in which hundreds of women participated. Kerala Nadvathul Mujahideen, a reformist movement among Muslims in Kerala then extended whole-hearted support to Haleema.

Haleema was also a freedom fighter and a staunch opponent of the Travancore Diwan CP Ramaswamy Iyer.

The Diwan who was loyal to the colonial rule used all his powers to suppress political movements in Travancore. Leaflets and notices against the Diwan rule and the British used to be printed at Haleema Beevi’s press which drew the wrath of the Diwan.

Haleema recollects this in an interview given to Chandrika Weekly in 1995, her last before she passed away in 2000.

“I was called for a meeting with the Diwan. He promised a job in the government if I stop political activities. I refused that offer as it was equivalent to compromising our liberty,” (Chandrika Weekly, July 1995).

Not many know that Kerala’s leading daily, Malayala Manorama was once banned in 1938 during the freedom movement and its press was shut down by the Diwan. It is said that the then editor of Malayala Manorama sought Haleema’s help and she allowed them to print leaflets and other materials in a clandestine manner at her press. However, there is no historical recording of it. Such contributions remained mostly limited to oral anecdotes.

Much later, due to her political activism, she was elected councillor to the Tirur Municipality as an LDF candidate in 1995.

“The information that we could gather regarding her political activism is incomplete,” says Noorjahan. “She (Haleema) used to be loyal to the Congress , but how far she was a part of the Muslim League, I don’t know,” says Noorjahan.

The authors of Haleema Beevi’s biography vouch that many things accomplished by her would not have materialised without the ardent support of Moulavi.

Despite many firsts, Haleema Beevi finds almost no mention in the history of literature nor that of journalism in Kerala.

“When I talked to many Muslim intellectuals (men), they all agreed that they started their writing career with the support of Haleema Beevi. But none of them could give me a satisfactory explanation for not writing her biography or keeping her memories alive,” says J Devika in the introduction to the book.