- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why is this 88-year-old historian riling Stalin and other Dravidianists

The door was ajar. When this reporter was about to knock, a family member ushered him in. A man was sitting shirtless on the sofa with his sacred thread visible across his chest, poring over some papers through a watchmaker’s lens. His ash-smeared forehead glistened as he stood up to wear a shirt before talking to this correspondent. It was a recent weekday morning at a Chennai...

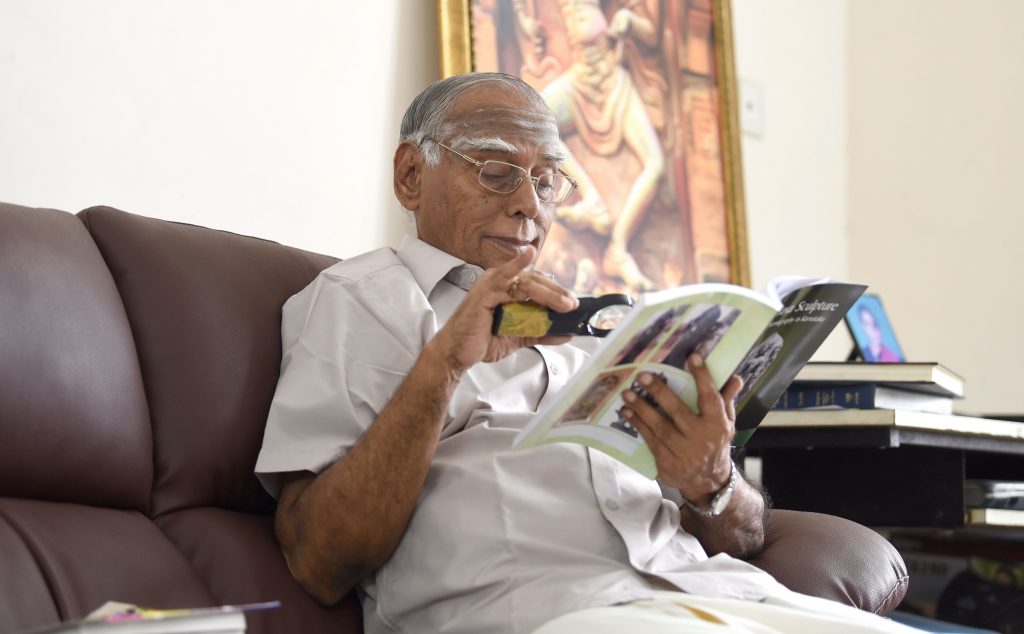

The door was ajar. When this reporter was about to knock, a family member ushered him in. A man was sitting shirtless on the sofa with his sacred thread visible across his chest, poring over some papers through a watchmaker’s lens. His ash-smeared forehead glistened as he stood up to wear a shirt before talking to this correspondent.

It was a recent weekday morning at a Chennai neighbourhood and Nagaswamy seemed composed, seemingly unmindful of the political storm he was caught in. A renowned archaeologist and epigraphist, he had served for 22 years as the founder-director of the Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department. His department was founded during the chief ministership tenure of M Karunanidhi, and Nagaswamy has helped to excavate records and artefacts that have reconstructed the history of Tamils over thousands of years. His discovery of the Pandian port of Korkai provided architectural evidence for the Sangam-era Tamil civilization, circa 500 BC. Nagaswamy’s contributions have testified to the greatness of ancient Tamil culture and have buttressed Dravidian politics in their own way.

But, now Nagaswamy, a Padma Bhushan awardee in 2018, is facing bitter criticism from the Dravidianists with DMK president MK Stalin lashing out at him recently. They say that Nagaswamy’s recent works and utterances strike at the very heart of Dravidianism, which is that Tamils have a non-Vedic Hindu past during which their lives were fairly irreligious, non-Sanskritic, even casteless.

The immediate provocation was his appointment as a jury member of the Classical Tamil Institute Award Committee by the Central government. The awards are given by the President of India.

Dravidianists see the appointment as yet another ploy to subvert Tamil identity since Nagaswamy seems to sync with the Sangh Parivar narrative on Tamil history and culture. They cite the Centre’s move to stall archaeological excavations at Keezhadi, near Madurai, which has proven to be yet another source of architectural evidence of the Sangam era. They also charge that the Centre is starving the Classical Tamil Institute of funds.

Tussle over a text

Nagaswamy has been taking contrarian positions over the last three-four years, which have riled Dravidianists since he is a scholar of repute and good credentials. For instance, Nagaswamy has said that the script in ancient inscriptions found including in temples is derived from a northern import. He has averred that there is no evidence to the theory that Tamil predates Sanskrit, contrary to what Dravidianists say. He also said that Tholkappiyam, a Sangam-era grammar text, is derived from Sanskrit works.

But, at the heart of the current fracas is ‘Thirukkural – An abridgement of sastras’, a book he published in 2017. This work argues that the ancient Tamil law book, Thirukkural, is derived from Hindu dharmashastras such as Manushastra, Arthashastra, and Kamashastra. In his book, Nagaswamy has shown parallels between some of the Thirukkural verses with those found in Hindu texts.

This has hit Dravidianists at a sensitive spot. Among the many ancient Tamils texts, Dravidianists have held up Thirukkural as the epitome of Tamil culture.

Thirukkural, said to be 2,000 years old, is a book of values and ethics, and appears irreligious. To Dravidianists, Thirukkural is an example of the highly ethical life that Tamils lived millennia ago. They say it was a life that was sullied by brahmins who came in later and brought with them rituals and the caste system.

Dravidianists see in Nagaswamy’s book evidence of the negative influence of brahminism in Tamil culture. “Such attempts will only fuel anti-brahminism among Tamils who are aware of the role played by brahmins,” says Kali Poongundran, deputy president of the Dravidar Kazhagam (DK), an organisation founded by Periyar which is considered a forerunner of all the Dravidian parties.

Suba Veerapandian, founder of the Dravida Iyakka Thamizhar Peravai (DITP), which is a splinter organisation of the DK, says: “Whoever speaks against Dravidianism and Tamils will get a high position in Delhi or other institutions. Nagaswamy has succumbed to the temptation.” On March 9, cadres of the DITP burnt the pages of Nagaswamy’s Thirukkural book at Chennai.

Suba Veerapandian, founder of the Dravida Iyakka Thamizhar Peravai (DITP), which is a splinter organisation of the DK, says: “Whoever speaks against Dravidianism and Tamils will get a high position in Delhi or other institutions. Nagaswamy has succumbed to the temptation.” On March 9, cadres of the DITP burnt the pages of Nagaswamy’s Thirukkural book at Chennai.

Cheyon Murugan, who has been promoting a musical form of Thirukkural, says just because there are parallels between the shastras and Thirukkural doesn’t mean one was derived from the other. “Tolstoy had an influence on Gandhi. But that doesn’t mean Gandhi’s teachings are an ‘abridgement of Tolstoy’,” he adds.

“This whole controversy is ‘a dishonest discourse’. Nagaswamy’s claims have not been met academically,” says writer Badri Seshadri who has been critical of the Dravidian movement. “Nagaswamy is not being refuted in a scholarly way,” he says, adding that his opponents are attacking him politically.

Seshadri says Nagaswamy’s recent writings do show a rightist tinge. “But that doesn’t mean he is an enemy of Tamils. One must remember that most of the inscriptions, which speak volumes of the richness of Tamil culture, have been fleshed out because of Nagaswamy alone,” he said.

Scholar unperturbed

Nagaswamy is sticking to his guns. Quoting scholars who have studied Thirukkural like Parimelazhagar, Father Beschi (who is called Veeramamunivar in Tamil) who lived in the 17th century, Ellis who lived in the 18th century, G U Pope who lived in 19th century, and U Ve Swaminatha Iyer of the 20th century, he says, “They have all said Thirukkural has its roots in the Vedas.”

For instance, a Kural verse says spirits of dead ancestors, God, guests, kin and self should be cherished. A Manusmriti verse says he who does not cherish God, guests, servants, spirits of dead ancestors and self is dead though he may be physically alive, Nagaswamy points out.

Nagaswamy is dismissive of the criticism that the Central government gave him the Padma Bhushan in 2018 because of his recent sayings upholding the idea that Tamils are a part of the pan-Indian Hindu mainstream. “They could have given the award because of my book. But I did not write the book for getting the award”.

“People accuse me that I am inclined to right-wing politics. But I am apolitical,” he adds.