- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

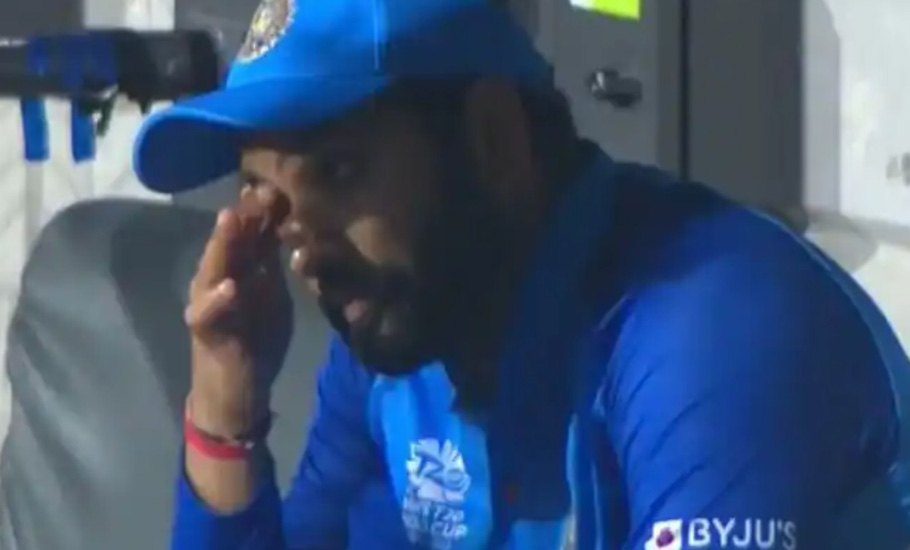

Why India looked off the boil in T20 World Cup

India had one full year, and a new management team, to work on the problem areas that ushered them out of the T20 World Cup in 2021 at the first time of asking. Having publicly proclaimed a fear-free, aggression-first batting policy and followed that template for the 35 matches that straddled their World Cup campaigns, India came badly unstuck at the 2022 T20 World Cup. Their...

India had one full year, and a new management team, to work on the problem areas that ushered them out of the T20 World Cup in 2021 at the first time of asking. Having publicly proclaimed a fear-free, aggression-first batting policy and followed that template for the 35 matches that straddled their World Cup campaigns, India came badly unstuck at the 2022 T20 World Cup. Their embarrassing ten-wicket defeat to eventual winners England in the semifinal can hardly be ascribed to one bad day in office, given that avowed intent was hardly backed up by commensurate results, or even effort.

While it might be tempting to lay the blame on India’s stuttering run to a complete meltdown of the bowling on the back of their hammering at the hands of England, the top-order batting can’t be absolved of blame. In six innings, India topped 40 just once in the Powerplay. Even considering that the pitches were a lot more challenging in early-summer Australia and it was well nigh impossible to hit through the line with impunity like in the subcontinent or England, these are disappointing returns for a team that boasts a wealth of international experience, and can draw on players who have been part of the IPL landscape for a decade and more.

Despite trying out as many as 29 players between the World Cups, India reposed faith in nine of the 15 men who did duty in the UAE last year. That number would have climbed to 11 had Jasprit Bumrah and Ravindra Jadeja not been rendered unavailable through injury. To the uninitiated, that might suggest a paucity of options but that’s hardly the case. India have a larger talent pool than anyone else to choose from and ought to have been less conservative in their selection. By sticking with several all-format players and refraining from packing the squad with T20 specialists, they weren’t doing themselves any favours.

At a time when workload management has become the popular refrain and there is a stated investment in Test cricket, it won’t be the worst idea to free up many of the Test regulars and invest in those that excel in the 20-over game. England rejigged their limited-overs philosophy in 2015 after failing to reach the quarterfinals of the 50-over World Cup.

If, after two successive sub-par efforts in the T20 World Cup, India are reluctant to follow suit, it will point to an ostrich-in-the-sand syndrome which will preclude any light at the end of a dark, foreboding tunnel.

At least now, there should be a decisive shift towards a younger team. Three members, skipper Rohit Sharma included, are on the wrong side of 35 and former captain Virat Kohli celebrated his 34th birthday during the World Cup. There certainly is a place for experience even in this format, as Ben Stokes proved emphatically during the tense run-chase in Sunday’s final against Pakistan, but dour experience at the expense of exciting youth is a definite no-no.

Having taken over with great expectations, head coach Rahul Dravid faces an acid test one year into his tenure. India are already sitting on three consecutive overseas Test losses, and for all their stupendous bilateral T20 form – they were unbeaten in ten series between the end of the last World and the start of this one – the inability to crack the semifinal riddle for the fourth time on the trot must count for something. At the highest level, one is judged only by numbers and by performances in big tournaments. India didn’t reach the final of either the Asia Cup in the UAE in August-September or this World Cup, and while that isn’t an indictment of Dravid’s methods, it shows that the team has some way to travel before it can make a consistent pitch for top honours in multi-team competitions.

Advancing years and the vast outfields in Australia showed up India’s fitness and fielding standards. In a format where every run saved is a run scored, India were off the boil more than they were switched on. The uncompromising fitness standards under Kohli seem to have eased off somewhat; the think-tank must begin to crack the whip and Rohit must lead by example if India aren’t to be left trailing in the wake of the stronger, fitter, faster sides.

For the first time in many years, India’s lead-up to the World Cup was perfect. They reached Australia a good fortnight before the start of the tournament, spent a week in Perth getting used to a changed time zone and spicier decks, had two official warm-up games in Brisbane (one of them washed out) and came into the tournament as battle-ready as can be expected. Their stirring opening-game win against Pakistan, fashioned by the brilliance of Kohli, ought to have been the stepping stone but India never looked like they were playing at full tilt.

Kohli and the admirable Suryakumar Yadav came to their rescue time after time, undoing the damage done by the underachieving openers, and the bowling was incisive in helpful conditions, though once they ran into a flat track against England in Adelaide, they seemed bereft of ideas and imagination. The lack of pace in the Indian bowling was always going to be a big factor; India perhaps missed a trick by not investing more heavily in the raw speed of Umran Malik because as Pakistan reiterated in the low-scoring final, a top-class pace attack is a massive weapon even in the batting-friendly T20 format.

It’s almost certain that a couple of the World Cup players have already played their last T20 Internationals and that some others might have just a few more games left in them. That will necessitate a wholescale overhaul, and that wouldn’t be coming a moment too soon.

India will host the 50-over World Cup next year and travel to the US and the Caribbean in 2024 for the next T20 World Cup. If the quest for an ICC trophy should not spill over into a decade and more, immediate course correction is required. Seemingly harsh calls will have to be made, no matter how high the profiles of the players concerned, because no individual is bigger than the game and because India’s passionate fans who keep the sport vibrant and healthy deserve better.