- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why everybody wants to appropriate Thiruvalluvar

‘To pierce a mustard seed and let in seven oceans.’ That’s how ascetic Idaikaadar described poet and philosopher Thiruvalluvar’s epic work Thirukkural– a book of 1,330 couplets written in Tamil. What Idaikaadar was referring to is the vastness of the subjects the couplets address and the depths of the philosophical plunge they take. Idaikaadar, it is claimed, lived in the Sangam...

‘To pierce a mustard seed and let in seven oceans.’

That’s how ascetic Idaikaadar described poet and philosopher Thiruvalluvar’s epic work Thirukkural– a book of 1,330 couplets written in Tamil. What Idaikaadar was referring to is the vastness of the subjects the couplets address and the depths of the philosophical plunge they take.

Idaikaadar, it is claimed, lived in the Sangam age, which lasted from about the 6th century BCE to around 3rd century CE. If Idaikaadar was asked to talk of the work today, he probably would have said, ‘To pierce a mustard seed and let in a thousand claimants.’

And that is because today, as Tamil Nadu celebrates Thiruvalluvar Day, everyone wants to claim Thirukkural as their own without understanding the work’s true essence. In recent years, both Thiruvalluvar and his work, Thirukkural, have assumed a greater importance beyond their literary and philosophical merit.

The poet, his work, and the snaffling

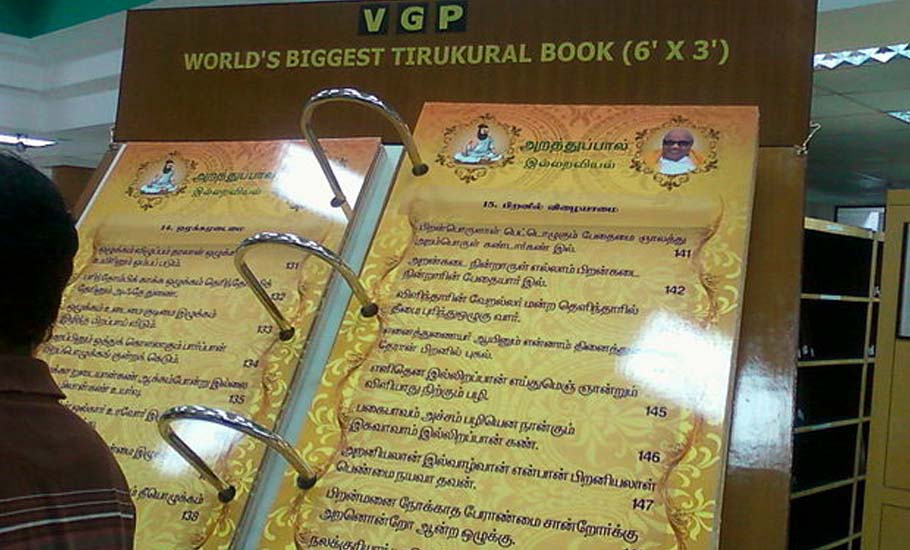

Written by Thiruvalluvar around 2 BCE, Thirukkural has 133 chapters, each with 10 couplets. Each couplet, in turn, has only seven words and are divided into three broad sections—aram (virtue), porul (wealth) and inbam (love).

Some claim that after the Bible, it is the most translated book. By not invoking any particular god, Thirukkural has earned itself the title of Ulaga Pothumarai (the holy book of the universe). In Tamil Nadu, Thirukkural is part of the Tamil language syllabus under the state board. Even marriages are solemnised by reciting couplets from the book.

The couplets, originally written on palm leaves, were first published as a printed book by British civil servant Francis Whyte Ellis in 1812. It was first translated into English by George Uglow Pope in 1886. Later, multiple translations of the book came up in English and other languages. In 2021, the book was translated into Hindi by TES Raghavan. For his work on the book, Raghavan received the Sahitya Akademi’s award for best translation work in Hindi.

Apart from the translations, many Tamil scholars have written on the couplets. These Urai (texts) offer explanations of the couplets.

A simple Google search for Thiruvalluvar, popularly known as Valluvar, shows a bearded man with a head bun clad in a white robe. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, he holds a stylus in the right hand and a palm leaf in his left.

However, the history behind this image is interesting. Like most other ancient figures, including kings and queens, who lived in an era when the camera or even portrait painting had not caught on, the image of Thiruvalluvar on the internet is born purely out of the imagination of an artist. Renowned painter KR Venugopal Sarma in the 1950s picturised Valluvar out of his love for the book. Sarma’s, however, wasn’t the first effort to give a shape to the imagination of how Thiruvalluvar looked. Many tried but their efforts were rejected because all of them tried to ascribe religious identities to him.

It was after the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam came to power in 1967 that the then Chief Minister and founder of the party, CN Annadurai, recognised Sarma’s Thiruvalluvar portrait as the official image of the saint poet. Annadurai also ordered to have the picture of Valluvar in all the state government institutions. In order to popularise Thirukkural among the masses, the government ordered all the state-run buses to have a couplet from the book painted behind the driver’s seat.

Although Thirukkural’s couplets talk about concepts such as god, karma, rebirth, heaven, hell, vegetarianism, among others, it is still considered by the scholars as a non-religious book, since most of these concepts are universal in nature and found in the teachings of many religions.

As Thiruvalluvar’s own religious beliefs remain an open debate, researchers based on their own interpretations claim that he practised Buddhism, Saivism, Vaishnavism and Christianity. Some claim that he was a Brahmin, since the word ‘Anthanan’ (another word for Brahmin, according to many scholars) is found in several instances in the book. Some also claim that he followed Ajivika, an ascetic sect.

The most popular opinion, however, on Thiruvalluvar’s religion is that he followed Jainism. This idea has been put forth by well-known Tamil scholars such as Thiruvarur Viruttachala Kalyanasundaram (Thiru Vi Ka), S Vaiyapuri Pillai, historians such as Mayilai Seeni Venkatasamy, and Tho Paramasivan. Even foreign nationals such as Kamil Zvelebil, a Czech scholar on Dravidian languages, buys the argument that Thiruvalluvar was a Tamil Jain.

So, how did they reach the conclusion?

Mani Maran, a Tamil scholar and a librarian at Saraswathi Mahal Library in Thanjavur, says the assumption was drawn by scholars based on ancient history of Tamil Nadu.

“The period when the Thirukkural was written was the time Jainism held fort in the Tamil land. It was patronised by the then kings and followed by many people. Besides Thirukkural, many other moral texts such as Jivaka Chinthamani, Kundalakesi and Naladiyar were written by Jain saint-poets. Since Thirukkural is also a moral text, it was naturally presumed that one of the Jain saint poets could have written it,” he says.

Intriguingly, the name Thiruvalluvar is itself not a real name. In Tamil, the word ‘valluthal’ has different meanings such as ‘to sharpen’, ‘to provide’, ‘to donate’, etc. The word ‘Thiru’ is used as a respectful prefix. The poet is respectfully called ‘Thiruvalluvar’. Moreover, the poet has not written his name anywhere in the text suggesting that he might have got the ideas from various sources.

According to Trichy-based Thirukkural scholar Navai Sivam, many try to appropriate Thiruvalluvar as a man of their religion based on the wordings found in the book.

“Take for instance, the usage of the words ‘thaal vananguthal’ [literally falling at someone’s feet or prostrate as an act of veneration]. It is a practice commonly followed in Jainism. Again, Christians claim that like Jesus Christ gave the ‘Ten Commandments’, Thiruvalluvar also wrote 10 couplets in each chapter and hence he was a Christian. Muslims claim that the book was ‘Thiru Quran’ and only later renamed as ‘Thiru Kural’ and so Thiruvalluvar was a Muslim,” he says.

According to Sivam, Thiruvalluvar was born and lived in Nanjil Nadu, which constitutes present-day Kanyakumari district and surrounding regions. “Some words like ‘Oorani’, denoting a water body, are still used by people in Kanyakumari.”

Madurai-based Thirukkural Valarchi Kazhagam founder Krishnan says Thiruvalluvar is not only being appropriated by various religious groups, but also caste groups like the Valluvar community, which is a scheduled caste. Historically, they have been working as astrologers, barbers, traditional healers and temple priests.

“What one can definitely claim is that Thiruvalluvar was a Tamilian, since Thirukkural was originally written in Tamil,” he adds.

Until the emergence of Dravidian nationalism, Thiruvalluvar was largely thought of as a Jain. With the rise of Periyar, Thiruvalluvar started to be projected as an atheist. It is interesting to note that much before any Tamil scholar or organisation working towards popularising Thirukkural, it was Periyar who conducted the first ‘Thirukkural conference’ on January 15, 1949.

What Periyar says at the event can be summed up as: “The first chapter of the book Thirukkural was titled as ‘Kadavul Vaazhthu’. It does not denote any Gods that are idol-worshiped. But they talk about how humans should attain God-like qualities. The couplets discuss topics held in high esteem by humanity.”

Hindutva hues

Over the years, Tamils have bought both the arguments – Thiruvalluvar being a Jain saint poet and Thiruvalluvar as an atheist. But in 2019, a book authored by renowned historian and archaeologist R Nagaswamy disturbed Dravidianists and other Tamil nationalists who believe Thiruvalluvar was a Jain.

Titled Thirukural: An Abridgement of Sastras, Nagaswamy’s book claims that Thirukkural is actually based on the four vedas – Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva. Incensed, the cadres of Dravida Iyakka Tamizhar Peravai set fire to copies of the book near Valluvar Kottam in April that year.

Adding fuel to fire, in November 2019, the Tamil Nadu state BJP unit tweeted an image of Thiruvalluvar wrapped in saffron attire. The images showed him wearing rudraksha and his forehead smeared with sacred ash.

The BJP tweeted the image soon after Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Thai translation of Thirukkural in Bangkok. This was followed by Arjun Sampath, chief of Hindu Makkal Katchi, draping Thiruvalluvar’s statue in a saffron shawl.

It wasn’t the first time the BJP tried to paint Thiruvalluvar in saffron hues. In 2015, then BJP Rajya Sabha MP Tarun Vijay, while advocating that Tamil should be made a national language, used a similar image and a placard printed in Tamil urging the members of the Upper House to follow the path shown by Thiruvalluvar.

The placard read, “Let Thiruvalluvar bless us and guide our path in Parliament.”

While the controversy settled then, Vice-President Venkaiah Naidu sparked a fresh row, when his office tweeted a similar picture of Thiruvalluvar to mark his birth anniversary on January 16, 2020 (the poet’s birth anniversary falls on January 16 during leap years).

In June 2021, a ‘saffronised’ image of Thiruvalluvar kept in Tamil Nadu Agricultural University was removed and replaced with the official image which shows Thiruvalluvar in white.

On January 7, 2022, the current Tamil Nadu Governor RN Ravi, while inaugurating the International Thirukkural Conference in Coimbatore, kicked up a new controversy by stating that the “spiritual quotient” of Thirukkural are ignored due to “perverse politics”.

“We are all children of God. Many have realised the godliness with or without idols. Thiruvalluvar too may have realised the godliness by reading texts from various religions or through the experiences of other humans. That was why he had used the word ‘deivam’, another Tamil expression to denote God. But he never indicated any particular God. Similarly, he talks about souls, but nowhere does he say that the human soul is the greatest. When we read superficially, we misunderstand the true meaning,” says K Ganesan, founder, Thirukkural Ulagam Academy, Coimbatore, an organisation that aims to propagate the teachings of Thirukkural to younger generations.

Each year, ahead of Thiruvalluvar Day on January 15, educational institutions and associations which popularise Thirukkural, conduct couplet recital competitions and elicit enthusiastic participation. Tamils also follow ‘Thiruvalluvar year’, an officially recognised Tamil calendar system.

In November 2021, Chief Minister MK Stalin wrote to the Union government to consider announcing Thirukkural as the ‘national book’.

Over the centuries, Thirukkural has become an identity marker for Tamils blending into the state’s culture and polity. Yet, the politicisation continues.

Everyone’s to blame

Noted cultural writer Po Velsamy says that not only the Right, but what the Dravidianists did was also appropriation. “In the 18th century, Christian missionary Constantine Joseph Beschi translated Thirukkural into Latin. Reading that text, many missionaries came to Tamil Nadu. In the 19th century, it was evidently proved that Thirukkural is basically a Jain text. In the 20th century, when Dravidian politics was at its peak, two other Tamil works – Tholkappiyam, a comprehensive text on grammar, and Silapathikaram, one of the five Tamil epics, were projected along with Thirukkural as identities of Tamil culture,” he says.

By projecting the antiquity of Tamil language, culture, society and polity at the national level the Dravidian parties drew political mileage, he adds.

According to Velsamy, if only Thirukkural’s Jain connection had been popularised adequately, people would not have fallen for distorted history and claims.

Interestingly, the appropriation continues even though, as Thirukkural Valarchi Kazhagam founder Krishnan explains, most of the couplets have become redundant in today’s world.

“The couplets talk about avoiding meat and not indulging in adultery and infidelity. But all these have become normalised in today’s world. Similarly, people nowadays don’t want to associate themselves with any religion,” he says.

That is why, Krishnan adds, instead of looking at it as a moral or religious subject, Thirukkural should be seen and read as a guidebook to life.