- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why do exit polls in India lack credibility?

Since the early 1990s, the conduct of public opinion surveys on various issues has been in vogue.

Since the early 1990s, the conduct of public opinion surveys on various issues has been in vogue. Particularly during election time, such surveys or opinion polls attract considerable attention. Equally important, though hardly surprising, is the fact that they evoke a great deal of controversy. Assessments about population behaviour based on data from a carefully drawn sample are of course...

Since the early 1990s, the conduct of public opinion surveys on various issues has been in vogue. Particularly during election time, such surveys or opinion polls attract considerable attention. Equally important, though hardly surprising, is the fact that they evoke a great deal of controversy.

Assessments about population behaviour based on data from a carefully drawn sample are of course not altogether free of error. There are two distinct types of errors. One is called, in technical jargon, ‘sampling error’ and arises from the sample design itself. The magnitude of this error can be worked out precisely after the sample design is given, and the forecast based on the sample design can be denoted as being subject to this margin of error in either direction.

The other type of error, called non-sampling error, arises from the actual process of collection of data. This category includes errors in observation, measurement and recording. This error cannot be estimated with any degree of precision but can be minimised considerably, though not completely eliminated, by exercising great care in the process of data collection.

Carefully designed opinion surveys have potentially far more of an objective basis than impressionistic reports of journalists in the print medium or political commentators on the electronic media. What should be expected of any serious pollster is that the methodology — the entire gamut of details, including sample design, field work methods and procedures, and analytical procedures by which inferences concerning the population are drawn from sample data — is explicitly and transparently stated.

Electoral forecasts: a complex exercise

To be fair to the pollsters, one must recognise the enormous practical problems that confront anyone who seeks to make electoral poll predictions in India. First of all, there is the sheer size of the electorate. Second, a vast territory, some of which is not easy to access, has to be covered within a fairly small interval of time. The electorate is highly heterogeneous in terms of language, culture, rural or urban residence, levels of formal education and many other variables of relevance.

All these features do not, of course, make forecasting necessarily less reliable. But they do imply high costs and time constraints in getting the poll done. The data needs to be processed quickly to meet print or electronic media deadlines. Invariably, corners are cut, and rigour in terms of sampling design and an adequate sample size often suffers. Besides, even the best sampling design is by itself inadequate to ensure reliable predictions. There are significant non-sampling errors such as inadequate quality of actual data collection in the field.

Read more: Regional pollsters tell a different tale from national ones

Then there is the very difficult and complicated problem of converting vote share into seats in an electoral system where the first-past-the-post is the sole winner. Moving from vote share predictions to seat forecasts is especially complicated when there are more than two serious contenders or contending political formations, as is often the case. Again, when there are two nearly equally strong contending formations, even a small change in vote shares can imply dramatic changes in the number of seats won. Kerala is an example where even a small swing can make a considerable difference, and a third force deciding to transfer its votes to one of the two main formations can also affect the results decisively.

There are many weaknesses in respect to methodological transparency in opinion polls in India, including implicit and explicit biases of various kinds. Many serious problems remain. While sampling design can be improved, it carries with it the implication of a higher cost. Most of these polls are in the nature of hothouse exercises, done to meet near-impossible deadlines, causing large non-sampling errors. Moreover, the mode of communication/presentation of the results of these surveys, to an audience which is always presumed to be in a hurry so that the focus is on bytes, also has its pitfalls.

Exit polls in India lack credibility

Pre-poll surveys in India have improved over time in terms of sampling designs and reduction of sampling errors, but have a long way to go in significantly reducing non-sampling errors arising in the process of data collection. Exit polls, on the other hand, the way they are conducted in India, are methodologically very poor.

A proper exit poll should choose a large enough random sample of constituencies. It must then draw a random sample of voters from the list of all voters in each of these constituencies. It must visit the chosen sample of voters and interview them in an environment free of external pressure. Only then there is a proper statistical basis for inference.

In Indian exit polls, however, voters are typically accosted as they come out of polling booths and asked to say who they voted for. In some exit polls, voters are contacted over the phone. This immediately introduces a bias in that those not owning and using a phone get excluded. Besides, there is the problem of replacing those not responding to the phone calls with others who respond.

Apart from the samples being non-random in both cases, there is an obvious bias in favour of ruling party in such a situation. Those who voted for the ruling party are far more likely to respond than those who did not, both in the vicinity of the polling station/public location and over the phone.

Consider, for instance a Muslim or dalit voter in Uttar Pradesh. This voter is unlikely to respond to a question on who she/he voted for, given the polarized context and the insecurity some sections of the population feel. Even the average SP-BSP mahagathbandhan voter is likely to give our pollster a miss. The result, even if unintended, is an over estimation of the vote share of the ruling party and an underestimation of that of the opposition.

Exit polls as media events?

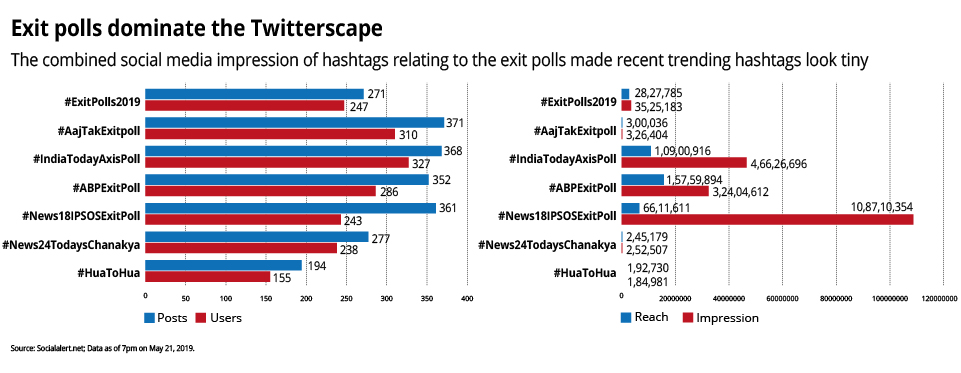

The track record of exit polls in India has been none too impressive. In several Lok Sabha and Assembly elections, exit poll forecasts have not only been wide off the mark, but have also substantially differed among themselves. Ironically, this has happened even when the same agency carried out the exercise for different clients in the same election! Yet, the exit polls attract a great deal of attention. They have become big media events. The role of corporate interests in manipulating both the conduct of the exit polls and the communication of their results on media platforms cannot be altogether ignored. Media outlets and polling agencies have a strong interest in ensuring that exit polls attract audiences and attention on a very large scale.

Read more: Exit polls confound, crown Modi king

In addition, there is the role of powerful forces close to corporate media/non-media interests with a stake in the outcome of exit polls. This can be so even though it is the case that exit polls can have no influence on the electoral outcome if the counting process is lawfully done. Exit poll outcomes made public seem to inspire significant speculation in financial markets.

Consider, for instance, the dramatic rise in the Sensex on the heels of several exit polls suggesting that a single-party majority or a stable coalition led by the incumbent party may form the new government. There is thus a potential additional incentive for pollsters to resort to methods of polling and of inference that project both continuity and a stable government. Even if this aspect is ignored, the simple fact is that exit polls in India are unscientific and biased in favour of the ruling dispensation.

In the current context, fears have been expressed that exit polls might have been manipulated to make the ruling party’s victory achieved through possible large scale manipulation of the voting and counting processes appear plausible. Without subscribing to conspiracy theories, one is unfortunately constrained to observe that, in the prevailing sharply polarised circumstances, considering the enormous stakes involved and the steady weakening of constitutionally mandated institutions in India in recent years, this fear cannot be entirely discounted.

(The writer is an economist and political commentator.)

(thefederal.com seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. In case of articles by contributors who are not staff of thefederal.com, the information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not reflect the views of thefederal.com)