Why deciphering inscriptions is the first step to understanding history

Three years ago, archaeologists who were in-charge of excavations at Keeladi noticed an interesting behaviour among the people who flocked to the site from the nearby villages and towns. The visitors would enter the site in the Sivaganga district of Tamil Nadu and then start collecting the potsherds scattered around. After collecting the leftover potsherds, they would try to assemble them. The idea was to ascertain whether there were remains of any ancient script or symbol incised on the broken pieces of pottery. They were not trained in epigraphy, which is the study of inscriptions. But they knew that inscriptions play a major role when it comes to the history of a place and its people.

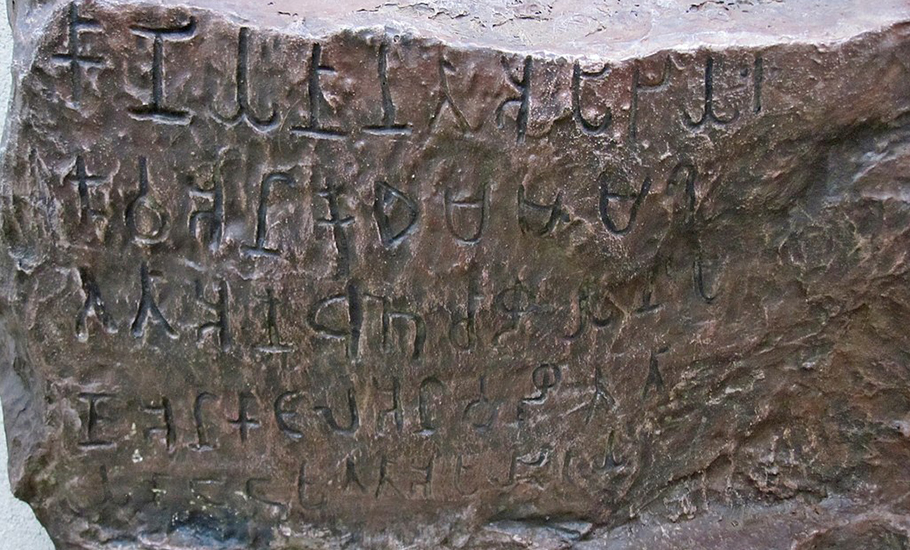

So what does ‘inscription’ mean? It means any writing engraved on an object. It can be a rock, metallic plate or pillar, brick or pot. If there is no inscription, then there is no history. India, according to Y Subbarayalu, senior epigraphist and winner of the V Venkayya Epigraphy Award 2022, owes a lot to inscriptions when it comes to the history of the country and its people. “The history of Tamil country from the fourth to the 17th century could not have been written, as we know today, without the help of inscriptions. The statement is true for other regions of India too. Literary sources have no doubt supplemented the inscriptional sources, but the chronology of the Tamil literary works has been built on the basis of inscriptions,” he said.

In Tamil Nadu, archaeological excavations have been undergoing at various sites and many brought in a number of significant objects other than inscriptions which are being used to study the history of the region in detail. So, why are inscriptions so important?

“As inscriptions are least subject to revision they are more reliable than other sources. They, particularly the stone inscriptions, do not move much from their original location. Inscriptions are easily datable and that is the first and foremost requisite for being a historical source,” said Subbarayalu. “Another good characteristic is their normally prosaic or sober nature unlike the literary works. The eulogistic portions, of course, display some features of myth and legend, which have their own value for understanding the ideology of the ruling class. Otherwise, the inscriptions concern only with matter-of-fact things,” he added.

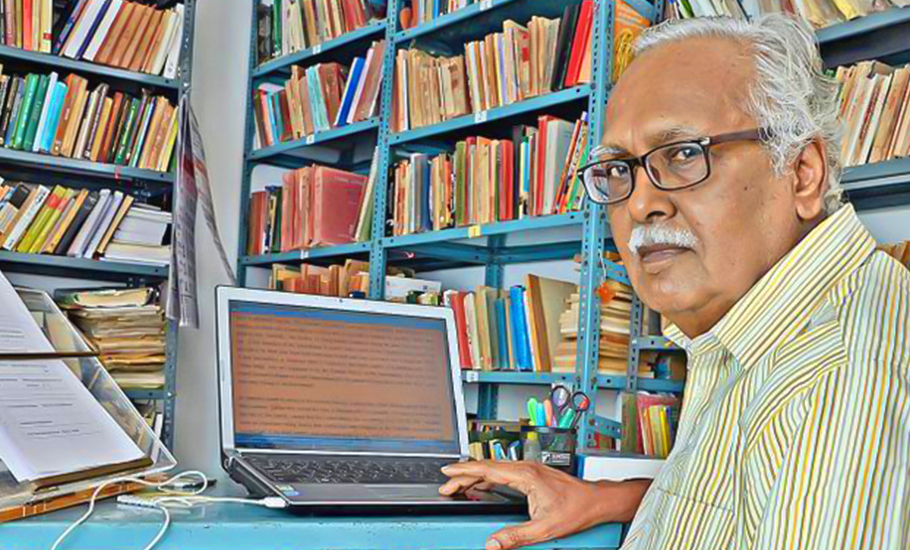

However, it is also a fact that there is a bias in them in that most of them relate to temples and religious things. That is, inscriptions cannot and do not give all the information about several crucial things that a comprehensive understanding of history would require. “The society that is represented in those records comprises mostly the upper and propertied strata of the day. The landless, working groups get only a marginal importance in them. A large chunk of the society thus goes unrepresented and unnoticed. To retrieve the history of this section requires sophisticated historical methods, either Marxist or non-Marxist,” said Subbarayalu, who won the debut V Venkayya Epigraphy Award 2022 instituted by Sunitha Madhavan, the great-granddaughter of V Venkayya, the first Indian chief epigraphist to the government of India.

Born in 1940, Y Subbarayalu is one of India’s most prominent epigraphers and historians. He has held several academic positions in institutions such as Madurai Kamaraj University and the Tamil University, Thanjavur. He also served as visiting professor at University of Tokyo and EPHE, Paris. As an epigraphist, he led archaeological excavations at several places in Tamil Nadu, which include Vallam, Kodumanal and Periyapattinam. He was also a member of the Indo-Japanese project for archaeological explorations in Vietnam, Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Kampuchea and Sri Lanka to study Southeast Asia’s trade and cultural contacts.

For writing Tamil inscriptions, Brahmi (Tamil-Brahmi) script was used until the fourth century CE, thereafter two parallel scripts, namely Vatteluttu and Tamil, were used until the 10th century, and thereafter Tamil became the sole script while the Vatteluttu script was confined to Kerala. The script called Grantha was used from the fourth century onwards to write the Sanskrit inscriptions or Sanskrit passages found in Tamil inscriptions.

“It is now understood clearly that the Vatteluttu script emerged from the Tamil-Brahmi script and the Tamil and Grantha scripts emerged from the Southern Brahmi script. There is, however, a difference of opinion regarding the exact chronological relation between the Brahmi/Southern Brahmi scripts on the one hand and the Tamil-Brahmi script on the other.

Iravatham Mahadevan’s book on Tamil-Brahmi and early Vatteluttu epigraphy has brought in fresh perspectives on our understanding of the early scripts. But there still remain some problems dating the early stage of the Tamil-Brahmi script in the light of the Brahmi graffiti found on pottery excavated from several sites in Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka,” he added.

As an epigraphist, Subbarayalu feels only about 50 per cent of the Tamil inscriptions collected so far have been edited and published properly. “There is a big task awaiting the epigraphists of publishing the rest. As far as the literary manuscripts are concerned, generally we get more than one manuscript for the same text and therefore it is possible to arrive at the correct text after making a comparative study of the different manuscripts using methods of textual criticism. For inscriptions, with certain rare exceptions, there is generally only one version available,” he said.

“Since the inscribed stones are damaged in many cases due to long exposure to sun and rain and also due to human factors, good texts of the inscriptions can be obtained only after long and patient decipherment. The reliability of the texts thus made depends upon the time and care spent on individual inscriptions. Though there are several epigraphists to read Tamil inscriptions, they are not sufficient enough to handle the thousands of inscriptions, which remain unpublished,” said Subbarayalu, who is the author of many books, including Political Geography of the Chola Country, A glossary of Tamil inscriptions, and South India under the Cholas.

As regards the texts of inscriptions available in print, there are differences in quality among the publications of different agencies. Subbarayalu said even among the South Indian Inscriptions series there is no uniform standard. “While the earlier volumes contain useful historical introductions and translations to each inscription, the latter volumes have only the bare texts in Tamil (or some other language). These latter volumes are not so attractive or easy for lay scholars to use. There are now a few useful indexes and lists which may be used as guides to refer to these inscriptions,” he added.

The epigraphy branch of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has copied and deciphered at least 74,000 inscriptions found in different parts of the country so far. Inscriptions were meant by their authors to be primarily records of charity, seeking religious merit (puṇṇiyam) for the donors and for their dear and near.

“In a way they were a medium for self-advertisement. Incidentally, they were also records of property rights. There is no systematic chronicling of past events and no deliberate recording of economic and social information, except in some inscriptions that could be treated as purely royal records or administrative ones,” he said. Contrary to popular belief, a majority of the inscriptions constitute non-royal or non-state category. “If taken individually, the inscriptions have only bits or fragments of information. They become really meaningful only when the inscriptions of a particular locality or of a particular time segment are considered as a group. Using individual inscriptions to prove a point is reliable to a limited extent only.”

To prove his point, Subbarayalu pointed out KA Nilakanta Sastri’s work on Uttaramerur inscriptions, where the scholar very judiciously used the entire corpus of Uttaramerur inscriptions to give a complete picture of a Brahmaṇa settlement and its corporate body, the sabha. “Most other scholars refer to only the two famous inscriptions of the early 10th century dealing with the rules for the constitution of the committees of the sabha and give only a hazy picture of the subject,” he added.

Asked whether he was happy to receive the V Venkayya Epigraphy Award 2022, Subbarayalu said, “I am glad that I have been chosen for the award instituted in the name of a great epigraphist.”