- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Who’s older? Halmidi and Talagunda locked in a battle over Kannada inscription antiquity

Halmidi is one among the 2,418 villages housed in Hassan district of Karnataka. But Halmidi isn’t just any other village. For the past nine decades, Halmidi, with a population of a little over 1,500, has enjoyed the distinction of being the place where the oldest Kannada inscription was born, dating back to 450 AD. The inscription was, in fact, named after the village itself raising...

Halmidi is one among the 2,418 villages housed in Hassan district of Karnataka. But Halmidi isn’t just any other village. For the past nine decades, Halmidi, with a population of a little over 1,500, has enjoyed the distinction of being the place where the oldest Kannada inscription was born, dating back to 450 AD. The inscription was, in fact, named after the village itself raising its importance on the historical and cultural map of Karnataka.

But Hassan’s Halmidi has found a challenger in Shivamogga’s Talagunda. The two villages are currently locked in a paleographic debate over the antiquity of the two inscriptions.

“The inscription found in Talagunda is around 80 years older than the one that was found in Halmidi. The Talagunda inscription dates back to 370 AD,” Keshava Tirumalai, a retired superintending archaeologist of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), told The Federal.

The antiquity of Kannada has been a topic of serious discussions for over a century now.

According to linguists, Kannada has more than 2,500 years of unbroken history and it is the third oldest language, after Sanskrit and Tamil. Of the six classical languages of India declared so far, Kannada ranks third and the Union government accorded the classical language tag to Kannada in 2008.

At a time when Karnataka is all set to celebrate the golden jubilee year of its formation and 15th year of Kannada acquiring the status of one of the classical languages of India, the discourse over the oldest Kannada inscription has found a lot of traction. Linguists are engaged in a heated debate on whether Talagunda inscription is more ancient than Halmidi stone inscription.

In support of Halmidi inscription

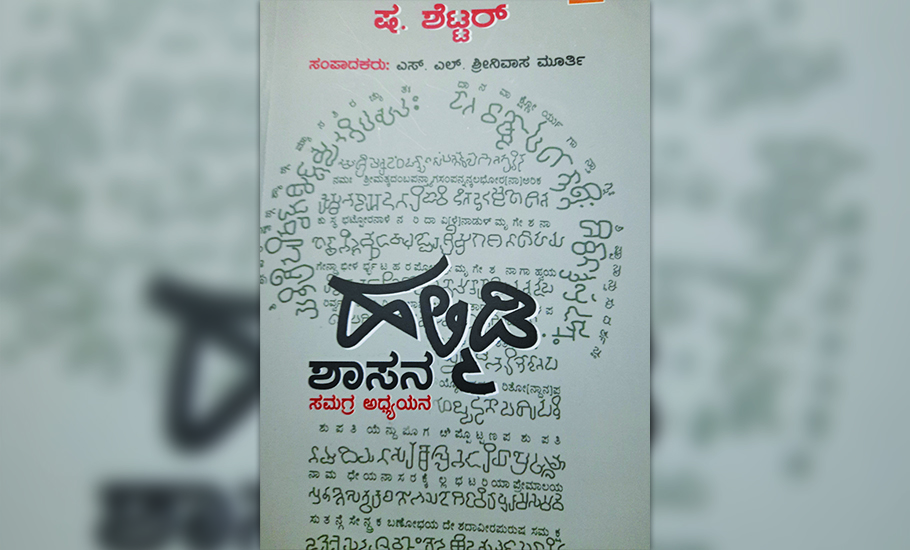

At this critical linguistic juncture, Abhinava, a 30-year-old prominent publication in Kannada, which brought out over 500 important works in all literary genres including classical character of Kannada published Halmidi Shasana: Samagra Adhyayana (Halmidi Inscription: A Comprehensive Study), a 256-page volume edited by renowned scholar Dr SL Srinivasa Murthy.

This work has paved the way for a detailed discussion on the antiquity of Kannada. Significantly, late Shadakshari Settar, renowned scholar, who conducted research in the fields of Indian archaeology, linguistics, art history, history of religions, philosophy and classical literature, is the chief editor of this volume.

This collector’s volume has 36 in-depth essays written by stalwarts of Kannada literature including MH Krishna, Govinda Pai, S Srikanta Shastry, M Mariyappa Bhatta, M Chidananda Murthy, Thi Tha Sharma, DL Narasimhachar, TV Venkatachala Sastry, MM Kalburgi and Ka Vem Rajagopala.

Publisher N Ravikumar dedicated Halmidi Shasana to MH Krishna, an archaeologist, who concluded eight decades ago that Halmidi is the oldest Kannada inscription available and published the details of his study in the Mysore Archaeological Report. Krishna shifted Halmidi inscriptions, which were lying in a mud fort in Halmidi village, to the Archaeological Museum and later to the Government Museum in Bengaluru.

“The inscription found at Halmidi near Belur dates back to 450 AD, and it happens to be the earliest record inscribed in Kannada characters. The language used in this inscription is being classified as Poorvada Halegannada (primitive Kannada) with distinctive characteristics resembling those of Tamil,” noted linguist and author MV Seetharamaiah said in his book Pracheena Kannada Vyakaranagalu.

Despite contributing largely to the antiquity of Kannada language, Halmidi remained neglected until, realising the linguistic importance of this hamlet, Kannada Sahitya Parishat transformed Halmidi into an important cultural and literary centre in 2006.

According to the annual report of Mysore Archaeological Department (1936), Halmidi inscription is not only highly important for the history of the Kannada language, but it also throws light on an important political event and on contemporary political conditions. Besides, hinting at sacrifices of the time, this inscription points at the practice of kings making grants to the brave warriors.

The report also delves into the place where this linguistically significant inscription was found in 1936. The report says that the old mud fort wall of Halmidi village has now disappeared. Close to where its west gate stood five years ago, buried under earth, a dwarf stone pillar with some writing on it was found. The villagers installed it in front of the temple and used to tie cattle to it. Children practised aiming by hitting it with stones and damaged many of the characters. The Archaeological Department discovered it in this condition and transferred it to the Archaeological Museum after recognising its importance.

The report also offers a fascinating description of how the inscription looked. “The pillar is four-feet high, one foot broad and nine inches thick. It has three parts — a foot evidently cut with the intention of inserting it in a corresponding hollow in a base slab, a body about 18 inches high, with two sides well planed and inscribed and a head ten inches high, which is shaped like a horse-shoe arch, with a small projection at the top. In the centre of the head is a circle seven inches in diametre provided with ‘S’ form spokes. It represents Sudarshana Chakra of Vishnu. The head bears the first line running in a horse-shoe form around the chakra. The face of the body bears lines. The 16th line is written on the right side of the stone running from top to the bottom. The inscription which is on a variety of soap stone is in a comparatively good state of preservation, except for the fact that the stones thrown by the village boys have damaged the upper lines and caused shallow pits in about a score of places making a correct reading difficult. The total number of lines is 16. Each letter is roughly about 2/3 inches long and half an inch broad.”

Favouring Talagunda inscription antiquity

Talagunda, where the recent inscription was found, is located around five kilometres away from Balligavi, which served as the centre of learning during the times of Kadambas of Banavasi. It is the birth place of great Veerashaiva saint Allama Prabhu and is closely associated with Vachana poet Akka Mahadevi. It is also believed to be the original home of the Kadambas (345-540 AD), an ancient royal family of Karnataka.

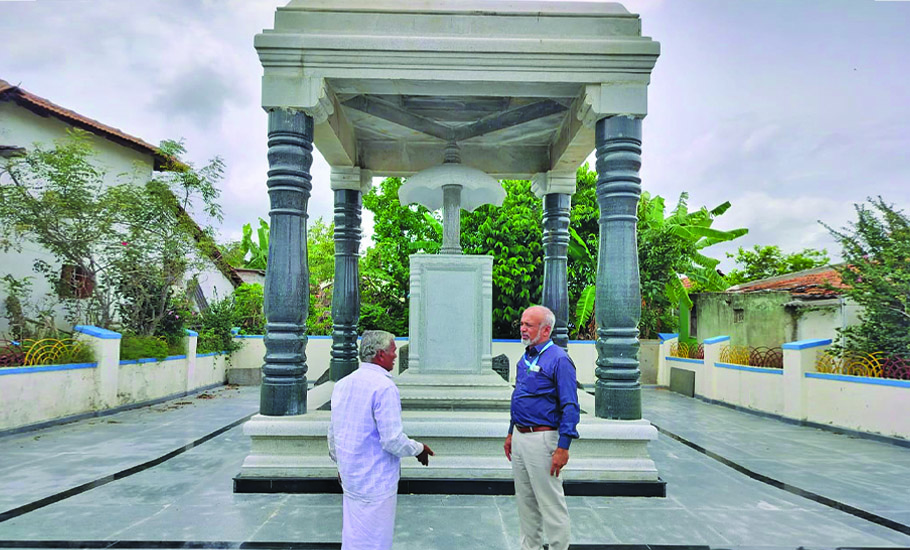

Talagunda, according to scholar and writer Ramesh D Hirejamburu, was a study centre during the Kadamba period. While carrying out excavations in Talagunda, archaeologists unearthed an inscription. This inscription was discovered on the back of lion-balustrade steps made of greenish grey schist stone in front of the temple. This inscription signalled the antiquity of Kannada and some scholars and archaeologists considered it as the first and oldest Kannada inscription.

The inscription pushed back the antiquity of Kannada by 80 years tracing it to 350 AD to 370 AD. When ASI notified the findings of excavation in 2017, Talagunda inscriptions became a point of discussion among historians, paleographers and archaeologists. The ASI officially notified its findings in the Archaeological Review Journal.

The sleepy village of Talagunda had first shot into the limelight following the discovery of a Kadamba inscription by British historian, archaeologist and educationist Benjamin Lewis Rice (BL Rice) in 1902. According to natives, the antiquity of this village can be traced to Satavahanas. The Pranaveshwara temple in this village is a major attraction for archaeologists and historians, as this temple was worshipped by Satakarni-a ruler of Satavahana Empire.

Pillar inscription

Talagunda has been famous for its pillar inscription which revealed mysteries surrounding Kadambas and their origin. According to a former ASI official, the Pranaveshwara temple was in a dilapidated condition. In the process of rejuvenation, stones surrounding the temple were removed and each one was given a definitive number. While removing the foundation stone, a new inscription on the back of the lion balustrade was discovered.

According to a review of Indian Archaeology 2013-14, published by the Director General of ASI, “It is a seven-line slanted Brahmi script written left to right. The use of Kannada, along with Sanskrit script makes it a dual-language inscription. The inscription records gifts of land to a boatman.”

The dispute

The discovery of Talagunda inscription has given impetus to the argument that the antiquity of Kannada has been pushed back by at least a century. However, few archaeologists and historians dispute the Talagunda inscription theory by citing use of ‘Nadugannada’ (Kannada of mid-era) and rationalising their argument that Talagunda inscription would have originated much later than Halmidi.

Dr B Rajashekarappa is among the people who disputes the conclusion over Talagunda’s antiquity. An epigraphist and linguist, Rajashekarappa in an article published in a Kannada daily argued that simply by being attested by archaeologists and historians, Talagunda inscription cannot become older than Halmidi. It is not the conclusive stand of epigraphists.

“In recent days, attempts are being made to claim that some inscriptions are older than Halmidi. I have presented papers arguing that none of them are more ancient than Halmidi with facts based on epigraphy and linguistic study,” he told The Federal.

He further stated that experts who are claiming that Talagunda is the earliest inscription, have not answered the questions he raised in the paper presented at Karnataka History Academy. “There is not even one complete sentence in the Talagunda inscription. There are isolated alphabets and words in that inscription.”

Nevertheless, historian S Settar, who was known for his multidisciplinary work, encompassing linguistics, epigraphy, anthropology, during a conversation with this writer before he passed away in February 2021, said, “Halmidi cannot be concluded as the oldest Kannada inscription. There are five or six other inscriptions, which are much older than Halmidi and Talagunda. I have undertaken a palaeographic study of all these inscriptions and studies and research will soon be able to establish the exact origin of written Kannada.”

Dr Settar has completed a detailed study spanning 10 years on early inscriptions in Karnataka.

According to Settar, the Ganga dynasty controlled most of south India, including current day Shivamogga district by the middle of the 3rd century. “Historians and paleographers strongly believe that Halmidi, the first written inscription in Kannada dates back to 450 AD. But, one has to realise the fact that it doesn’t provide any clue about its exact period that Ganga period inscriptions usually offer. The need of the hour is to comparative study all the inscriptions of the time to conclude the exact period of each and every inscriptions,” Settar says in his volume Halegannada: Lipi, Lipikara, Lipi Vyavasaya.

Settar was engaged in the study of inscriptions for over a decade before his demise and his plan was to bring out a research volume on inscriptions of the first millennium. In the process, he collected details of about 2020-plus inscriptions. Settar brought out a volume on Kappe Arabhatta Inscription, carved on a cliff overlooking the northeast end of the artificial lake in Badami. This inscription of 7th century is considered the earliest available evidence of poetic writing.

Regardless of the controversy surrounding which one among Halmidi and Talagunda inscriptions is the earliest written engraving in Kannada, epigraphists, linguists, archaeologists are unanimous in their opinion that the institution founded to study classical Kannada has to take up a comprehensive study of all the said Kannada inscriptions and reach a conclusion over which one is really the first written inscription in Kannada.

Kannada Sahitya Parishat (KSP) — an umbrella body of Kannada language in Karnataka is planning to organise a discussion on the antiquity of Kannada and Halmidi inscription.

“Parishat will accord priority to the study and research on Kannada inscriptions. There is an urgent need to train students of linguistics in the discipline of inscription studies,” KSP president Mahesh Joshi said.