- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

What AMU's Kishanganj centre tells us about Modi govt’s Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas

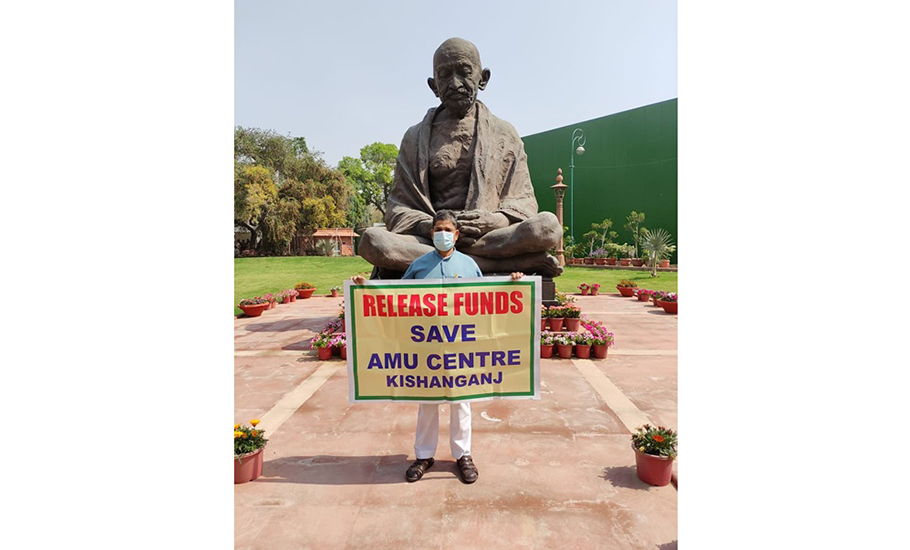

As Parliament’s budget session concluded on April 7, Mohammad Jawed, the Congress party’s Lok Sabha MP from Kishanganj in Bihar, stood in front of Mahatma Gandhi’s statue in the Parliament complex holding up a banner. For nearly two years now, Jawed has carried this banner to Parliament every single day of its various sessions. “Release Funds, Save AMU Centre Kishanganj” – the...

As Parliament’s budget session concluded on April 7, Mohammad Jawed, the Congress party’s Lok Sabha MP from Kishanganj in Bihar, stood in front of Mahatma Gandhi’s statue in the Parliament complex holding up a banner. For nearly two years now, Jawed has carried this banner to Parliament every single day of its various sessions.

“Release Funds, Save AMU Centre Kishanganj” – the banner reads. At times, MPs from the Congress or other Opposition parties join Jawed at the Mahatma’s statue to express solidarity with his cause. At others, he stands alone holding the banner aloft for passersby to see.

It’s a demand that Jawed has raised countless times inside the Lok Sabha too. He has repeatedly got fellow MPs to sign petitions variously addressed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, home minister Amit Shah, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, education minister Dharmendra Pradhan and minority affairs minister Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi.

And yet, as Parliament adjourned sine die, Jawed had got no assurance from the government of his demand being met. “I’ll keep raising this issue. Let us hope the government will concede,” Jawed told The Federal.

What is this AMU Centre that the Kishanganj MP has been pleading to save?

Sanctioned by the erstwhile UPA government of Dr Manmohan Singh back in 2012 following a sustained, year-long agitation by the youth of Kishanganj and adjoining districts, the centre is a branch of the iconic Aligarh Muslim University.

AMU-K was supposed to provide quality higher education courses to the people of Seemanchal – the districts of Kishanganj, Purnea, Araria and Katihar; a region of Bihar known primarily for its heavy concentration of Muslims and for its socio-economic backwardness. In its Union Budget for 2013-2014, the UPA government had allocated Rs 136.82 crore for the establishment of AMU-K of which the first tranche of Rs 10 crore was released at the time.

Nine years on, Jawed says the remaining Rs 126.82 crore allocated for AMU-K has still not been released by the Narendra Modi government that assumed power in May 2014.

In the meantime, cost escalation due to inflation, increasing requirements for making the Centre fully functional and other logistical demands have pushed up the fund requirement to an additional Rs 352.75 crore, explains AMU-K director professor Hassan Imam.

With delays in the Bihar government allotting land for AMU-K and funds being withheld without any explanation by the central government, the institution has been floundering. On paper, the campus was supposed to come up on a sprawling 224.02 acre plot of land on the banks of the Mahananda River to be allocated by the state government but this never happened.

The allotment was challenged before the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in 2017 for alleged violation of various environmental norms. In August 2019, a technical team constituted by the Bihar government studied the proposed site for the AMU-K campus. In its report submitted to the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) and other authorities in November 2019, the technical team concluded that the proposed campus site was neither on the bed of the Mahananda River nor located within the river’s active flood plains. Over two years have now passed since that communiqué but the NMCG is yet to draft its final report, based on the conclusions of the technical study team, and submit it to the NGT.

With the allocation of the proposed 224-acre site caught in a legal stalemate, AMU-K has been operating out of utterly decrepit buildings, allotted temporarily by the Bihar government, that serve as the centre’s academic complex, administrative complex, library, and hostels for the over 130 boys and girls enrolled in the management course offered at the institution.

“The current campus, if you can call it that, functions out of a few buildings that were given by the Bihar government under a temporary, rent-free arrangement. Since the proposed structure for AMU-K couldn’t come up due to legal disputes over land allocation, lack of funds and other logistical problems, we started by offering only two courses, MBA and B. Ed. In 2018, we had to stop the B. Ed course because the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE) passed an order saying AMU-K did not qualify to offer the course,” said Imam.

The paucity of funds has obviously hit the institution’s capacity to attract students or offer more courses. “Depending upon the commitment and generosity of the Union Government, the AMU Kishanganj Centre strives to add three departments of studies and research every year, which would go a long way in its expansion,” reads a paragraph about AMU-K and its (uncertain) future on the official website of AMU.

Earlier this year, the Bihar government allocated Rs 10.50 crore to AMU-K for construction of a girls’ hostel that can accommodate up to 250 students. At a virtual ceremony to symbolically ‘lay the foundation stone’ for this hostel, AMU vice chancellor professor Tariq Mansoor spoke about his hopes of restarting the B.Ed course and offering a BA, LLB programme at AMU-K but pointed out that these could only begin if the flow of funds is streamlined.

Cautiously optimistic after the Bihar government’s decision, Jawed wrote to Union minority affairs minister Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi requesting allocation of an additional Rs 50 crore for construction of 250-bed hostels for boys and girls. However, there has been no forward movement on his request yet.

A senior faculty member at AMU told The Federal that the only reason he could think of to explain the central government’s passivity towards the institution is the “perception that a branch of the Aligarh Muslim University located in an area with an over 60 per cent population of Muslims will largely attract students from the Muslim community”. The faculty member said the past eight years had “repeatedly shown” that the Modi government wants to “systematically deprive Muslims of anything that can help them stand on their feet and demand their rights”.

“Denying the community education is an essential part of this scheme because without proper education, particularly higher education, they will automatically lose out on employment avenues and be forced to take up whatever work comes their way in the unorganised sector. The Sachar Committee report, which forced the UPA government to pump in more money for education and scholarship schemes for the Muslim community, had also concluded that a major cause of the socio-economic backwardness of the community was that it lacked access to good education. The current government seems determined to starve minority education institutions to the extent that they’ll have no option but to shut down,” the faculty member added.

Jawed, however, insists that analysing reasons for the funds crunch for AMU-K through the Hindu-Muslim binary “helps nobody” but grudgingly concedes that he can’t fathom why the Modi government is apathetic to “genuine demands for a thriving educational institution that can cater to the needs of Seemanchal”.

Last March, in an anguished appeal to the education ministry during a discussion in the Lok Sabha, Jawed had said, “I come from a land that had Nalanda and Vikramshila, which imparted education to the world in ancient times, but today it is our misfortune that we don’t have infrastructure to educate our own people,” Jawed says.

Muslims constitute nearly 68 per cent of the population of Kishanganj. A concentration that is much higher than the average 47 per cent Muslim population across the four Seemanchal districts. The state-wide average of Bihar’s Muslim population is a much lower 17 per cent.

There is no dearth of reasons to explain why the ‘Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas’ government must show greater urgency in ensuring that the AMU-K becomes fully functional without further delay. In 2017, a study sponsored by the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF), Bihar Office and titled ‘Status of Muslim Youth in Bihar, Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment’, had found a substantial difference in the literacy rates of rural and urban Bihar – 54.3 per cent and 69.1 per cent respectively.

The study that also analysed official data from the 2011 Census concluded that literacy rate among the Muslims of Seemanchal was among the lowest in Bihar. The study claimed that the literacy rate among Muslims in the districts of Araria and Purnea was 48.3 per cent and 43.1 per cent respectively while in Kishanganj it stood at 53.1 per cent and in Katihar at 45.6 per cent. In other words, the literacy rate in these four districts was substantially lower than India’s national literacy rate that the 2011 Census had pegged at 74.4 per cent or an even greater 77.7 per cent according to the National Statistical Commission survey of 2018.

Though education and poverty are not always interlinked – India presently is witnessing galloping unemployment rates and naturally a substantial chunk of jobless Indians are literate – it is pertinent to note that a NITI Aayog report released last year had also pointed out that Kishanganj and the adjoining district of Araria have the country’s worst multi-dimensional poverty index. The NITI Aayog’s report, based on National Family Health Survey 2015-16 and compiled with additional technical support from the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative and the United Nations Development Programme, pegged 64.75 per cent of Kishanganj’s population as multi-dimensionally poor while the figure stood at 64.65 per cent for Araria.

Jawed may not be willing to look at the smorgasbord of problems and challenges facing AMU-K purely as the result of the Modi regime’s tacit – and often explicit – attempts at denying Indian Muslims their constitutionally enshrined fundamental rights; in this specific case the right to education.

“If AMU-K takes off, it won’t be a centre of learning that is exclusively for the Muslims… like AMU-Aligarh, Jamia Millia Islamia or the Benaras Hindu University, AMU-K will also provide education to students of all faiths. This is an institution that is necessary for providing education to people from all over Seemanchal and nearby areas. If AMU-K fails, it will be a loss for everyone, not just the Muslims… as a people’s representative, my job is to keep fighting for the rights of my people, irrespective of the faith they follow. If I lose hope, how will I speak for their rights,” Jawed said.

Jawed’s view is evidently an idealistic one but it is difficult to completely ignore the possibility that AMU-K may have fared better if its nomenclature was more religion-neutral or the region it is supposed to cater to wasn’t dominated by the Muslims.

The past few years have seen the Modi government progressively reduce fund allocation for programmes and schemes that were envisaged to give better access to education to the Muslim community.

For instance, this year’s budgetary provisions slashed fund allocation for the Maulana Azad Education Foundation (MAEF) by a massive 99 per cent. Though the overall allocation for the Union minority affairs ministry went up by nearly Rs 210 crore this year – Rs 5,020.50 crore in 2022-2023 as against Rs 4,810.77 crore earmarked in 2021-2022, fund allocation for MAEF came down from Rs 90 crore in 2021-2022 to a meagre Rs 0.01 crore for the current financial year.

The central government also cleverly slashed funds for the ‘Skill development and livelihood’ schemes meant for religious minorities by bringing down the overall budgetary allocation for its ‘Total Skill Development and Livelihoods’ programme from Rs 573 crore of the previous year to Rs 491.91 crore in the current year.

For a government that routinely harks about its agenda of improving the plight of Muslim women, its hypocrisy on this score was also writ large in the budgetary cuts for schemes promoting ‘Leadership Development of Minority Women’. The funds allocated for 2022-2023 under the ‘scheme for leadership development of minority women’ was brought down to Rs 2.50 crore from the Rs 8 crore allotted in the last financial year.

These budgetary cuts were explicit proof of the Union government’s agenda of starving schemes meant for education of religious minorities – the largest chunk of which are the Muslims.

There are, of course, much worse attacks that the Indian Muslim is being subjected to in nearly every other sphere imaginable by the ruling dispensation’s foot-soldiers from the rabidly right-wing Hindutva brigade. The plight of AMU-K may appear insignificant compared to these graver atrocities but it follows the same pattern of alienation, subjugation and retribution against the Indian Muslim.