- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

What India's wobbly healthcare system needs to survive future crises

In the wake of the COVID-19, experts believe the Indian healthcare system needs a major revamp to deal with future pandemics of this scale.

History has shown that outbreaks come with a baggage of solutions — a good part of them devised by health experts after trial and error. The Spanish Flu that broke out soon after World War I had highlighted the importance of guidelines for infection control, brought about containment measures, including case isolation and closure of public places, apart from stepping up disease surveillance....

History has shown that outbreaks come with a baggage of solutions — a good part of them devised by health experts after trial and error. The Spanish Flu that broke out soon after World War I had highlighted the importance of guidelines for infection control, brought about containment measures, including case isolation and closure of public places, apart from stepping up disease surveillance. It also brought about sweeping changes in public health systems in the West.

Now, COVID-19 has made people learn new concepts — self-quarantine and physical distancing, which were employed a century ago too. With the pandemic far from over in India and across the world, it has lessons for governments and the healthcare system.

Need epidemics policy for infectious diseases

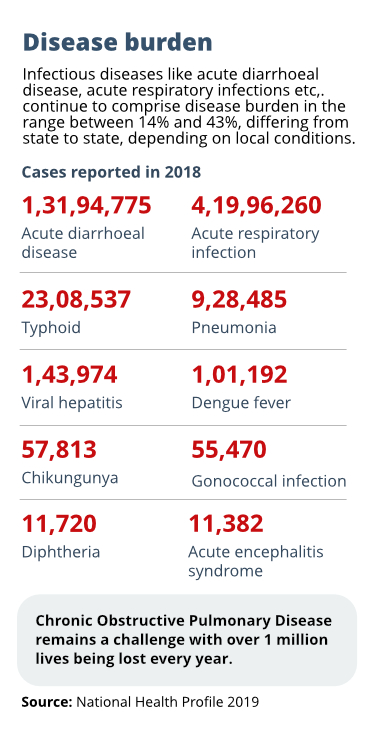

India had borne the brunt of the Spanish Flu outbreak, accounting for one-fifth of the global death toll at 18 million deaths. Since then, its struggle with infectious diseases has remained long-drawn. While efforts to combat smallpox, leprosy and polio have been widely successful, we continue to wage a war against tuberculosis and vector-borne disease like dengue and malaria.

Dr N Kumarasamy, chief and director, Voluntary Health Services – Infectious Diseases Medical Centre, and director of Chennai Antiviral Research and Treatment (CART), Clinical Research Site of US National Institutes of Health (NIH), says that the effort to tackle infectious diseases on an epidemic scale should begin by looking at a standard operating procedure (SOP) for the diseases.

“We do have some excellent policies for tuberculosis and leprosy that have helped us control them in a significant way, while malaria has been tackled and vector-borne diseases like dengue need more action. We are also grappling with diarrhoeal diseases every year,” he says.

But he pointed out that the policies used to tackle infectious diseases have a lacunae, though they have been effective. “What we need to develop now is an epidemics policy that is upgraded and fine-tuned, without deviating from the infection control pattern. The policy should have details of the SOPs for the diseases. This is probably the biggest lesson COVID-19 is teaching us regarding infectious diseases. We cannot take anything empirically. Even with COVID-19, India may seem comfortably ahead of others, yet it will remain a challenge, as we discover newer ways of transmissibility of the disease,” he says.

Dr Kumarasamy says that with the disease being around for months, infection control patterns should undergo a huge change in hospitals, that already offer a thriving environment for infections.

“Big hospitals are actually like bread boxes, without any ventilation, and with centralised air conditioning. The infection control practice within these setups should be improved as it can affect the safety of the healthcare provider and the patients. The protocol for ensuring these are not being practised and relevant authorities should address them. With crowded sitting areas, so many things can happen. Physical distance is not going to be followed after two months,” he says.

We should be prepared for a crisis like this, as even the best-prepared countries are reeling under it, says Dr V Ramasubramanian, senior consultant, infectious diseases, Apollo Hospitals.

“We have gained time and we should make an advantage out of it with a protocol for crisis situations. We should come up with templates for future purposes, with officers in charge and communication systems. We should also modify our work practices to get least affected by such outbreaks,” he says, observing that, “When you look at a country with over one billion population, anything is contagious — be it a plague, flu or COVID-19.”

Boost public health systems

A positive outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the public health response, observe experts. With healthcare workers from primary health centres involved in contact tracing and quarantine visits, and officials from various other departments such as police, civic bodies, doing their bit, one has to look up to them to build further, they note.

Dr Shakthivel Selvaraj, director, Health Economic Policy Unit, Public Health Foundation of India, says that the urgency for ramping up public health infrastructure is far greater now than before.

“While the immediate requirement is to tide over the deficiencies in intensive care units, ventilators, personal protective equipment (PPE), etc. in the government sector, it is equally critical to build the rural and urban public health infrastructure,” he says.

The government urban health infrastructure is virtually non-existent in most states, especially the primary health care infrastructure. The current gap is being filled by private healthcare or large government hospitals. “And government hospitals are expected to take up high-end serious care, involving surgeries, etc. but are burdened with treating outpatient care in large numbers.”

“In rural areas, the need for strengthening the primary healthcare infrastructure is equally critical because many of them are non-functional and even those that are functioning, do so with acute shortage of personnel, lack of consumables and medicines,” he adds.

Preventive care has assumed more significance with COVID-19, when all efforts are directed towards this front, says Dr Meenakumari Natarajan, project scientist, NIE-ICMR, health economist and epidemiologist.

“For COVID-19, we have no vaccines and we are focusing on the conservative approach of quarantine and preventive care. This is an indication that we should make a more robust preventive care system because through this 90% of the disease can be cut down,” she says, adding that preventive care also includes immunisation, health monitoring and education.

“These also include measures like screening of the vulnerable population; for example, women above 40 should be made to undergo mammogram compulsorily every year to detect breast cancers early. The focus should also be towards building trust in our public health system,” she says.

Rethink, revise budget

The immediate impact of the pandemic will be a moment of epiphany for policy makers, says Dr Meenakumari. “They might want to revisit the sum remitted and prepare ways to handle the disease better.”

India spends a paltry 1.2% of the GDP for health. “As envisaged in the Health Policy of 2017, India was supposed to spend at least 2.5% of GDP on healthcare by 2025, and with only 5 years to reach that milestone, it appears unlikely,” says Dr Selvaraj. “The COVID-19 pandemic spread has come as a wake-up call for governments both at the Centre and states to accelerate funding for health.”

While 80% of expenditure on health in India is out of the pocket, COVID-19 has altered the game, adding more costs for the providers.

S Manivannan, a healthcare management consultant, points out that costs accelerate with more clinical activities. “We found out that for two isolation beds, there is a need for 14 or 15 PPE which includes those for doctors and nurses in shifts and the cleaning staff as well.”

“Now, we also know that we cannot close the private hospitals for a longer time, as there are people waiting for transplants, cath lab procedures, etc. When you bring these patients for procedures, they may be asymptomatic. In such a case, even regular hospitals have to use PPE. I heard that in one hospital, where they had to treat a person in emergency for a fracture, the doctor, his assistant and the anaesthetist wore PPE,” he adds.

“We probably cannot have the same set of equipment and lab facilities for treating COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients. This is going to be a challenge for the government and they have to look into the incidence and magnitude of the cases in states and release the budget to states suffering the most,” he says, adding that one of the rules of the budget that states with less population will be getting less, will not be applicable in this scenario.

Build data

Data inadequacy and inaccuracy has been a major issue that often hinder policy and program implementation. This is more so owing to inadequate capture of epidemiological data relating to prevalence and incidence of various diseases.

The focus of the government statistics is more often tuned to gather information about processes rather than outcomes, says Dr Selvaraj. “The health information system in India has evolved in a haphazard and fragmented manner over time. In particular, the responsibility for collecting data on healthcare is divided among different ministries or institutions and between states, and coordination has become a challenge due to financial and administrative constraints. This is further exacerbated by the dominant private sector which hardly shares data with the public sector. Most epidemiological data do not get captured because a predominantly large number of patients get treatment from the private sector (70% of all outpatient visits and about 55% of hospitalisation occurs in private hospitals),” he explains.

Dr Selvaraj suggests two mechanisms that can improve the current data gathering effort — one is through strengthening the national government data systems with flow of information from relevant ministries at the Centre and state governments.

The second mechanism is to strengthen the information flow from private to public data sources. “The data parameters that are required for an efficient management of health systems are: epidemiological data (prevalence and incidence) on various disease conditions, health system indicators (health financing, health workforce, health governance, health delivery, health products, including medicines, vaccines and consumables, etc.). and efforts must be made to collect not only process-linked data but outcome-related data as well. One particular mechanism will be to implement the current national and state level Clinical Establishment Act and Rules for wider collection of data,” he says.

Involve community more consciously in health

One wonders why government’s measures are not taken seriously in India. A simple explanation, for example, would be the way in which many defied the concept of physical distancing in many cities across the country.

Dr G Srinivas, professor and head, Department of Epidemiology, Tamil Nadu Dr MGR Medical University, says, “Community participation has to improve and they have to shed the casual attitude about not being susceptible to illnesses. The fault also lies in our messaging — we say leprosy is curable, HIV is manageable. For a change, we should talk about the scary side of it, to get them to adhere. Tell them TB can affect their children. These messages can seem crude but work better.”

Experts also hope that physical distancing as a concept doesn’t die down after the lockdown and with the eventual disappearance of the disease. “With a crowded transport system and the typical scenes of crowded malls, a country like India faces the challenge of sustaining this as a practice,” notes Dr Kumarasamy.