- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

What cut short the Indian superheroes' cape

Superheroes have been flying over skyscrapers, popping out of thin air, free-climbing the world’s tallest buildings, all easy-peasy, for many decades now. Since 2008, in particular, Hollywood has been riding the superhero box office momentum kicked off by Iron Man. A decade later, all the capes, masks and superpowers are keeping the audience just as hooked, catapulting the year 2017 and...

Superheroes have been flying over skyscrapers, popping out of thin air, free-climbing the world’s tallest buildings, all easy-peasy, for many decades now. Since 2008, in particular, Hollywood has been riding the superhero box office momentum kicked off by Iron Man. A decade later, all the capes, masks and superpowers are keeping the audience just as hooked, catapulting the year 2017 and 2018 into what could be safely be called the cinematic superhero era.

It was during these two years that some of the biggest superhero movies of Hollywood, including Logan, Spider-Man: Homecoming, Wonder Woman, Thor: Ragnarok, Justice League, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Deadpool 2, and, Ant-Man and the Wasp became top-grossing films. What’s more? The movies fared well critically too.

Although eight superhero movies in the past have won Oscars for their technical advancements, 2017 was the first time a superhero movie (Wonder Woman) got nominated in the Best Picture and Best Director categories.

Writing about this growing craze for the genre, journalist Mark Bowden said, we are living in ‘Hollywood’s Comic Book Age’.

“A global obsession, superhero movies are seen by hundreds of millions, arguably the most consumed stories in human history,” Bowden wrote in an opinion piece for The New York Times.

While Bowden’s observation holds true for Hollywood, in India, interest in superhero movies has been akin to flashes in the pan. The recent success of Minnal Murali (2021) at the Indian Film Institute Survey of Top Critics has given hope that our superheroes aren’t done and dusted just yet. But how much of a fight do they really have in them?

Unlike Hollywood, the Indian film industry is not homogenous. With each superhero coming from a different ‘wood’, each representing a different culture and context, in India, there have been many superhero characters.

So, why is it that we do not have even one superhero, who can take on Superman, Spiderman, or Batman?

India’s tryst with superheroes

Before getting into how the Indian film industry fared on superhero films, it is critical to make a differentiation about how the term ‘superhero’ is widely understood in Hollywood and the Indian film industry. A superhero, for us, is a man or woman having exceptional magical powers, well versed in martial arts, attired in unique costumes and having a weapon to fight.

There are some Indian superhero films —a genre being explored since the 1980s — whose protagonist more or less fits the bill for this definition. These films include Guru (Tamil-1980), Superman (Telugu-1980), Shiva Ka Insaaf (Hindi-1985), Superman (Hindi-1987), Mr India (Hindi-1987) Shahenshah (Hindi-1988), Toofan (Hindi-1989), Ajooba (Hindi-1991), Krrish (Hindi-2006), Kanthasamy (Tamil – 2009), Mugamoodi (Tamil – 2012), A Flying Jatt (Hindi – 2016) and Hero (Tamil – 2019).

These men, women gifted with superhuman powers, are otherwise ordinary human beings, living among ordinary folks. While they live among us, the alter egos of superheroes would be revealed only when a time of turbulence would require them to save the day. The common folks would never know that the superhero is the same guy (or girl) living next door, known only for being too ordinary.

How does the ordinary metamorphose into the extraordinary? To begin with, by getting into an attire so tight that it would seemingly not allow even air inside. Although superheroes fly, they have no wings. All they have is their cape. They also have face or eye masks to complete the disguise. With the exception of a few superheroes, most have a personalised weapon to destroy the villains.

The similarity between the superheroes of Hollywood and Indian films ends there.

While superheroes of the West usually get their powers by serendipity, the Indian superheroes get their powers through penance (the child in the Telugu film Superman got his powers by persistently worshiping Lord Hanuman). It could be predestined (like Krishna, played by Hrithik Roshan, in Krrish).

Mastery in various martial arts is part of the package of the chance discovery of superhero powers in Hollywood. In Indian movies, drama is added as superheroes are shown being trained by teachers. In Shiva Ka Insaaf, Shiva, played by Jackie Shroff, was trained by three men. In Bhavesh Joshi Superhero (2018), Siku, played by Harshvardan Kapoor, is basically taking revenge from those who killed his friend Bhavesh Joshi (played by Priyanshu Painyuli). Siku, who impersonates Bhavesh to confuse the villains, receives training from Bhavesh’s martial arts teacher.

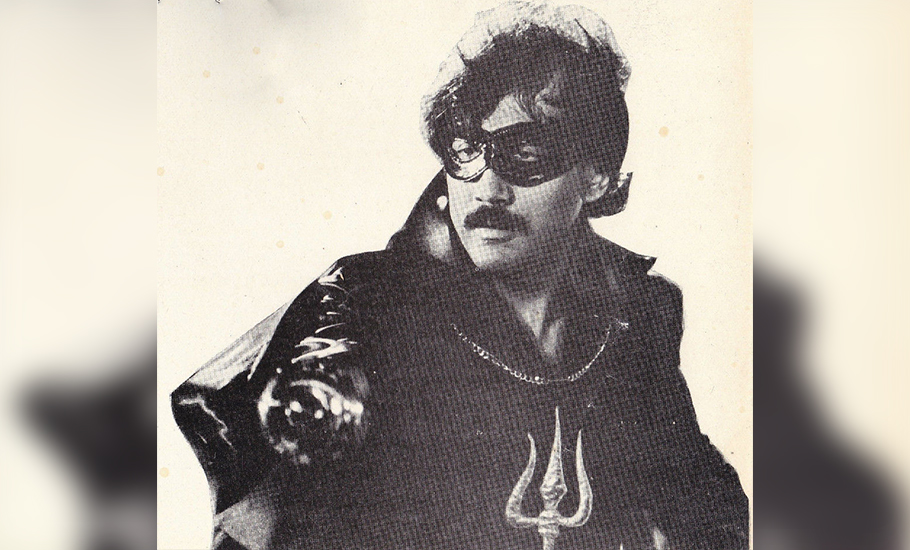

It is interesting to note that while the Western superheroes don’t have any relation with divine powers, some of the films evoke imagery from Christianity. When it comes to Indian superheroes, they usually have some or the other association with Hindu gods like in Shiva Ka Insaaf, the superhero wields a trident and claims to get superpowers from Lord Shiva and in Amitabh Bachchan-starrer Toofan (1989), the hero was a follower of Lord Hanuman and wields a crossbow as a weapon.

As with the story lines, with the exception of one or two movies, all Indian superheroes are out to avenge mostly personal wrongs. While at it, they also end up helping the larger society. The Western superheroes, however, have a much larger aim—to save the world from evil forces.

“If heroes are idealised humans, then present-day heroes reflect an exaggerated ‘Cult of Self’. They are unique, supremely talented beings who transcend laws, even those of nature. Hollywood has always cherished mavericks, but these are, literally, cartoons — computer-generated,” writes Bowden.

Compared to ‘computer-created’ superheroes, the Indian superheroes literally exist in flesh and blood. Their human element is enhanced by showing them to have some weaknesses, which mostly include familial attachments or baggage and prior failures in key missions.

One-time wonders

Dozens of superhero movies have been made in India. Some of them, such as Mr India (despite being an invisible superhero), Shahenshah, Guru and Toofan etc, have been box office hits as well. However, other than Krishh, no movie has been turned into a franchise. So, superheroes in Indian films, after ensuring the proverbial victory of the good over the evil, die with the film.

“Leave aside the sequels, in general, most Indian films do not make any sequels. For example, Japanil Kalyanaraman (1985) Tamil film, which was a sequel of Kalyanaraman (1979). It was the first film in Tamil which had a sequel. But that didn’t do well. So, for a long time, the concept of a sequel was literally not there. Only in the last decade, the Singam film series had successful sequels,” says Murali Kannan, a film enthusiast.

“When that is the case for normal hero-worshiping films, thinking of a sequel for not-so-hit superhero films is unimaginable,” he adds.

In India, while superhero films are watchable, they are still not a sought-after genre.

“The Tamil audience in particular wants heroes to be just heroes and not superheroes. They think that when the hero can fight on his own why does he need superpowers. Also, most heroes do not have a good physique so the cape and tight costumes don’t fit them. These are some of the reasons why the superhero genre is still at a nascent stage, at least in Kollywood, if not Indian cinema as a whole,” Kannan adds.

Dev Pandian, a film critic, agrees with Kannan. Pandian says since normal heroes can do extraordinary and entertaining stunts, having a low-profile, hiding his identity and romancing with heroines, an inter-alia kind of hero is not needed in the Tamil film industry.

“Many of Shankar’s films have shades of superhero movies but not in the truest sense. Films such as Kanthasamy (2009), where the character was inspired by a mythological Lord Murugan, could have become a superhero film. It had all the possibilities. However, the film failed to attract the audience since the screenplay had an overdose of logic. Mystery blended with heroism is the strength of the superhero films but Kanthasamy revealed the mysteries after every important scene like how the hero achieved that particular feat. So that people thought there was logic behind every scene,” he says.

Talking to The Federal, Mugamoodi (2012) producer Dhananjayan says there have been attempts made in Tamil cinema over the last 10 years to come out with a successful superhero film.

“But for all those attempts, MGR-starrer Malaikkallan (1954) set the precedent. It was that film that made him a superstar. Although he did not possess any superpowers in that film, the story was strong. Similarly, if you take the case of Minnal Murali, the film was a hit not because of the superhero but because of the story which is believable. The lightning that struck two people made one of them a good and the other an evil man. Superhero films in Tamil have missed convincingly conveying how heroes get superpowers. That made the audience dissatisfied with the subject,” he says.

Following the success of Minnal Murali, Dhananjayan adds, there are talks of recreating Mugamoodi.

“If we are able to correct the mistakes we made then, the film can still work out,” he says.

It is not only the Tamil films, but according to the novelist Samit Basu, Hindi films too are not up to the mark. In a blog written around the time when Krrish was released, Basu said “like their TV counterparts Shaktimaan, Aryamaan and Hatim, Bollywood’s superheroes thus far have mostly been badly produced, badly copied version of well-known western costumed vigilantes from film and comics, though Bollywood’s defenders might point out this is only right, given how vigorously early American superhero comics copied one another.”

Impact of Indian comic books

The origin of almost all Hollywood superheroes can be traced to comic books. Can such a thing happen in India, given the comics market of the country is niche?

According to Basu, Indian comics have “also featured a number of interesting spec-fic (speculative fiction) heroes from Chacha Chowdhury’s sidekick Sabu from Jupiter, to Amitabh Bachchan as the pink-clad Supremo in an Indrajaal Comics series featuring Bollywood script writer Gulzar, from half-machine RAW spy Koushik to Raj Comics snake-man Nagraj”.

“The heroes of Indrajaal comics, notably the dashing detective Bahadur, commanded genuine cult appeal and are cherished collectors’ items today. The superheroes of Raj, Diamond and Manoj comics also inspired a considerable fan following in India, thriving on local content, the intrinsic appeal of comics and lack of high-quality alternatives. Comprehensive lists are available on the Internet, created lovingly by fans who grew up devouring the adventures of Indrajaal Comics heroes Madrake the Magician and Lee Falk’s Phantom – indeed, the lack of memorable Indian superheroes is even more ironic when one considers that Phantom, widely believed to be the first comics action hero to wear a skin-tight costume, was originally based in India, in the ‘Bengalla’ forests, and his first enemies were the The Singh Brotherhood,” he says.

He adds that there are a surprisingly large number of Indian superheroes (like Dinesh Deol, Pavitr Prabhakar, Raz Malhotra, Shakti Haddad, Paras Gavaskar, Chakra, Aruna, among others) out there in the universes created by Marvel and DC, which no doubt means that there is a significant market among the South Asian diaspora for the comic series they feature in. And since Gotham comics started distributing Marvel and DC comics in India a few years ago, the demand could only have increased.

“The only thing that hasn’t happened yet, alas, is research. Indian characters continue to fit into standard roles, and we’re yet to see a South Asian comics hero who does for South Asians what Luke Cage did for African-Americans, or what Northstar did for the gay community,” he writes.

King Viswa, a researcher on comics, says the Tamil comics industry between 1940s and 1970s had its own superheroes like Minnal Mayavi. But they were forgotten when the publishers started to focus on translated versions of foreign comics because it was cheaper.

“When the comics industry here does not create Indian superheroes, it is meaningless to expect a film made here based on a comic book hero. But in Bollywood, because of the opportunities provided by various OTT platforms, now people are relying on graphic novels to adapt them into movies,” he says.

Basu says that the superhero genre becomes more and more complex, and succumbs to two major pushing forces–Hollywood, pushing it towards the pop-culture mainstream, and grown-up comic-books called graphic novels pushing it towards literature.

At this moment, having “multicultural, diverse heroes becomes a necessity to deal with an ever-growing, ever-changing audience not just in America, but across the world,” he says.