- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

What an archaeologist’s lifelong fascination with Ballari ashmounds unearthed

I was brought up in a place known for solid, rocky hills surrounded by monotonously plain land. Every day, I would gaze at the mounds of Sanganakallu lying at the perpendicular end of the road leading to my school—on the way back home, I would glance back at them several times until a bend in the road blocked the view. This was in Ballari, a sleepy little town in the 1960s. I was ignorant...

I was brought up in a place known for solid, rocky hills surrounded by monotonously plain land. Every day, I would gaze at the mounds of Sanganakallu lying at the perpendicular end of the road leading to my school—on the way back home, I would glance back at them several times until a bend in the road blocked the view. This was in Ballari, a sleepy little town in the 1960s.

I was ignorant of the archaeological importance of the hills though occasionally I used to hear from my father that ancient villages once existed there. But it was not clear how long ago. Even though there were other attractions around—the Ballari Fort hill for one, which is famous as the second-largest domal inselberg (isolated rock formation that rises abruptly from a flat plain) in the world—Sanganakallu was always at the back of my mind. At the end of that decade, I left for Pune (then Poona) and it wasn’t until the late 1990s that I returned to Sanganakallu as a well-trained archaeologist and with an archaeological problem to address.

What made Sanganakallu so special to investigators were the deep secrets its ashmounds held. And still hold. This is the largest Neolithic to Iron Age settlement in the South Deccan region—recent research has revealed that the site provides scope for further multidisciplinary investigations for a holistic reconstruction of the emergence and efflorescence of the agro-pastoral way of life leading to urbanisation in south India.

Datasets from excavations have revealed evidence of a successful adaptation to semi-arid climatic conditions since the past 5,000 years. Unfortunately, modern day economic necessities have been causing a great deal of harm and damage to the preservation of such an important heritage for posterity.

Herders’ Monuments

These ashmounds are also called Herders’ Monuments, meaning the first monuments built by our Neolithic ancestors who were cattle keepers. The person who first connected the Sanganakallu ashmounds with Neolithic culture and asserted that these were heaps of burnt cow dung was Robert Bruce Foote (1834-1912), a pioneer in the true sense of the term, who mounted on horseback, carried the torch of Indian prehistory and lit up many dark areas of India’s past. The geological community across the country regards Foote as the father of south Indian geology, whereas archaeologists regard him as the father of Indian prehistory.

Foote’s early work spanning 1870-1886 was followed by visits to Sanganakallu by F Fawcett, Robert Sewell and HT Knox in 1891, whose focus was on rock art at the Kupgal-Sanganakallu twin sites. In fact, the iconic image of interlocked bulls from the rock art of Sanganakallu is now being considered for the official logo of Ballari district following its bifurcation in 2021—just another reminder that even though the world-famous ruins of Hampi now fall within the newly-carved out district of Vijayanagar, the residual district of Ballari is by no means poorer when it comes to antiquity.

In the 1940s, professor HD Sankalia of Deccan College, Pune, advised his PhD student B Subbarao to retrace the footsteps of Bruce Foote in the Ballari region. This ushered in systematic archaeology at Sanganakallu. Subbarao revisited all the Neolithic sites in the Ballari region and identified more ashmounds, setting in motion a series of similar investigations at other Neolithic sites in the south Deccan region. Remember, this was before the era of radiocarbon dating.

When I was admitted for a masters’ degree in archaeology at Deccan College in Pune in 1972, what attracted me was a small showcase in the open corridor on the first floor displaying a model of Sanganakallu hills showing huts and stone tools against the background of a painting depicting a Neolithic village. I could recall my father’s musings and was excited about the importance of my native place and eager to go back to climb up the hills. I learnt about the work of Robert Bruce Foote, B Subbarao and HD Sankalia and his team at Ballari-Sanganakallu and that the region was rich in Neolithic and Iron Age settlements. Yet there was no answer to the question: How long ago did the ancients live on the hills?

The Neolithic Age did not convey much meaning to young archaeologists. Radiocarbon dating became common in India only after the mid-1970s. By then archaeological investigations in this area had stopped. Our textbooks were also silent on how many thousands of years ago the villages existed there and what food crops these Neolithic agro-pastoral communities cultivated.

Although I wished to take up this problem for my PhD at Deccan College, it wasn’t until well over two decades later that destiny brought me back to Sanganakallu with a full-fledged multidisciplinary programme in collaboration with scholars from a host of institutions in India and abroad. While I was a Charles Wallace-Ancient India and Iran Trust Fellow at Cambridge, I was introduced to Dorian Fuller (now professor at Institute of Archaeology, UCL, London), a budding archaeobotanist who wanted to undertake research on Neolithic agriculture and investigate south Indian sites.

This was a wonderful opportunity to go back to well-known Neolithic sites and reconstruct the history of agriculture during a period when the first hilltop sedentary agricultural settlements came into existence in southern India. Until then there was not much information on the nature of agriculture and types of food crops cultivated by the Neolithic people of this region. We selected nearly 40 previously investigated Neolithic sites in the semi-arid heartland of south India, between the Eastern and Western Ghats. This project has resulted in a holistic reconstruction of Neolithic lifeways in a chronological framework.

The archeobotanical findings

During the last two decades, Neolithic archaeology in southern India has crossed several milestones and has been successful in the application of interdisciplinary methods, including bio-archaeology and dating by the Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon method. This has contributed to identifying three distinctive traditions — the Ashmound Tradition, the Kunderu Tradition and the Hallur Tradition—in the developmental sequence of agro-pastoral economies, from the Neolithic to Iron Age between 3000 and 1200 BCE.

The Ashmound Tradition began earlier than the other two and survived for almost two millennia. These three traditions reveal successful adaptation to the largely semi-arid environments of the Late Mid-and Early Late Holocene fluctuating monsoon regimes.

The ashmounds represent deliberately accumulated cattle dung at designated places and set on fire episodically by the Neolithic agro-pastoral communities between 3000 and 1300 BCE. Recent analysis suggests that at a number of sites the ashmounds, which were not uniform deposits, predate the establishment of regular villages.

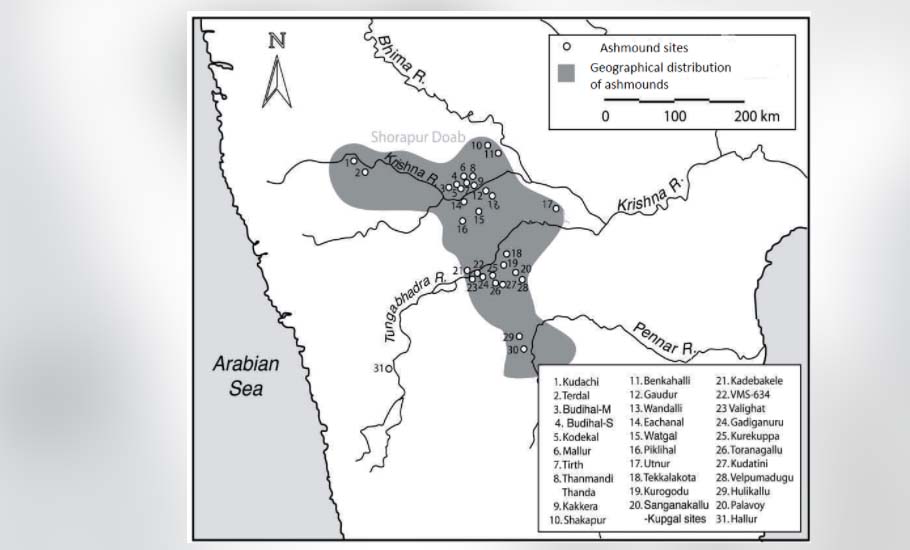

Among more than 150 ashmound sites in the region, about 30 have received focused investigations since the early decades of the 19th century. Recent perspectives have indicated their place in the ritual and fertility practices among the earliest agricultural communities in the region.

The archaeobotanical sampling has revealed a suite of food crops, both native and introduced, from a series of Neolithic sites along an east-west transect between the Western and Eastern Ghats. Of the plant remains, pulses were clearly the most prevalent. The most widespread pulse on Southern Neolithic sites is horse gram which has been recovered from all regions of the Neolithic Age thus far sampled. Green gram or moong is also widespread through the middle and later periods of the Southern Neolithic. The closely related black gram (urad) was less widely represented although it has been found from the Late Neolithic site of Hallur and from the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE) at Veerapuram in Kurnool district. Two other pulses that were probably later additions have been recovered from Southern Neolithic sites, including pigeon pea (tuar or arhar).

The staple crops of the Southern Neolithic were millets, dominated by a foxtail millet, in some cases to be identified with the bristly foxtail, although the yellow foxtail may also have been present. It is also possible that sawa millet, another grass that is a natural constituent of the peninsular grasslands, is present. The ubiquity and quantity of millets from recently studied sites strongly suggest their use as staple grains, especially foxtail millets, though it remains ambiguous whether these were actually domesticated or extensively gathered in the wild. The high level of purity of the samples, with relatively few other grasses present, argues for cultivation.

Two breeds of cattle have been identified from bones dominant in both the habitation and ashmound sites—one is long-horned, slender-bodied and humped like the zebu species and the other one massive but relatively short. Because of the importance of cattle, sheep and goats were relegated to a secondary position.

With the mining boom of the mid-1990s, the township of Ballari too was undergoing tremendous change—iron and steel industries and power generation stations had come up in the neighbourhood. Owing to inevitable developmental activities and modern day economic necessities, a vast majority of such sites have lost their identity. This situation is further aggravated by the lack of cultural resource management policy and public outreach archaeology.

Therefore, the need for establishing a museum for the Sanganakallu Neolithic site became necessary when we embarked on the multidisciplinary study. That public outreach programme has today culminated in a one-of-its-kind museum—with unstinted support from successive deputy commissioners of Ballari, several notable citizens and organisations.

The Robert Bruce Foote Sanganakallu Archaeological Museum opened in 2020 and is still a work-in-progress. But after a visit to the museum, a common man is expected to carry with him the story of human biological and cultural evolution up until the beginning of the historical era of written stone inscriptions.

A delightful gesture by way of preservation came in 2019 when the contractors of the highway connecting Ballari and Hosapet responded to our outreach archaeology and realigned it to protect an ashmound that was located in the middle of the four-lane highway loop. This ashmound will continue to stand majestically, thanks to the authorities of the Ballari Thermal Power Station.

If one can adopt at least one archaeological site in one’s lifetime, combined with effective public outreach, it will go a long way in the preservation of prehistoric cultural heritage lying buried underneath the surface.