- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

What an ancient village near Gaya says about the rise and fall of Buddhism

Bodh Gaya is a religious site in Gaya district of Bihar where Gautam Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. Monks from all over India and Asia would visit this Buddhist homeland quite often. While travelling to the erstwhile kingdom Magadha (today’s Bihar), these monks stayed in different monasteries, such as the one which was located in Kurkihar where a large collection of...

Bodh Gaya is a religious site in Gaya district of Bihar where Gautam Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. Monks from all over India and Asia would visit this Buddhist homeland quite often. While travelling to the erstwhile kingdom Magadha (today’s Bihar), these monks stayed in different monasteries, such as the one which was located in Kurkihar where a large collection of stone and cast images and other objects had been recovered. But why is Kurkihar, a village 27 km from Gaya, significant when it comes to the rise and fall of Buddhism?

Kurkihar was a Buddhist site holding a major position in the artistic production of the 9th century AD, waning thereafter without completely disappearing, according to scholar and author Claudine Bautze-Picron. “The artists of Kurkihar made use of the decorative vocabulary distributed throughout the region during that period, but introducing their own specific way of looking at it, permeating it with their sensibility and shaping it with a particular flavour thanks to which an image produced by their atelier can immediately be recognised,” said Claudine, who has studied various aspects of Buddhist manuscript illuminations and the iconography of the Buddha.

She said each motif plays a specific role within the overall programme or structure, occupying its own well-defined position. At the same time, it undergoes variations, alterations, like a word put through declensions. “While making use of the same ‘vocabulary’ as their colleagues from ateliers at nearby Bodh Gaya or Nalanda, to cite only two major sites active in that period, the artists from Kurkihar created their own idiom, their own treatment of it,” she said.

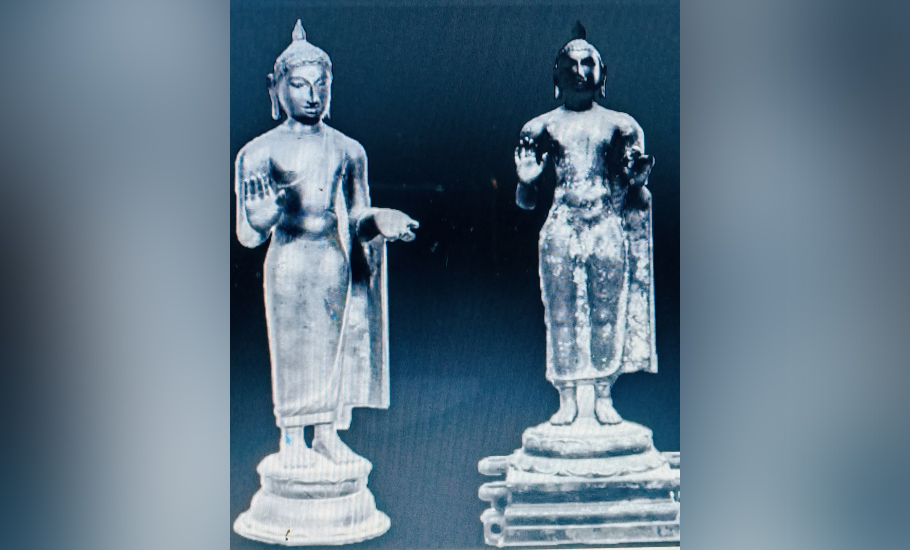

However, the monks who travelled from the south to Bihar during the 9th and 10th centuries had influenced the stylistic features of the artisans here a lot. “The monks from the south donated many sculptures of Buddha to the monasteries out there. I think the monks from Kanchi (today’s Kancheepuram in Tamil Nadu) brought with them miniature versions of the images of Buddha and asked the artisans of Kurkihar to reproduce it exactly the way they wanted. That’s why we can see the fusion of stylistic features of the south and the north in the sculptures made in Kurkihar. Some of them are inscribed with names of their donors who came from various cities like Kanchi and regions like Andhra,” said Claudine, while speaking on ‘Going North: Monks and Pilgrims from South India journeying to Bihar’ as part of the online monthly lecture conducted by the Tamil Heritage Trust recently.

There is no chance that the monks from the south got the sculptures from Kancheepuram when they travelled to Bihar those days. “Although the artists of Kurkihar possessed a unique style of their own, their artistic world was open to the developments that took place in the Buddhist ideologies of that time. The sculptures of Buddha displaying the Bhumispariamudra and Varadamudra stand testimony to it. The significance of Kurkihar has to be seen in such a way that the artists in the village documented through sculptures the changes that underwent in Buddhism during the 9th-10th centuries,” said Claudine, who is the author of Bejewelled Buddha from India to Burma, New Considerations, The Buddhist Murals of Pagan: Timeless Vistas of the Cosmos and The forgotten Place: Stone images from Kurkihar, Bihar.”

“The Forgotten Place: Stone images from Kurkihar, Bihar” is the result of a detailed study of the stone images found in Kurkihar by Claudine, according to whom the material has been documented from as early as 1847 when British architect Markham Kittoe visited the place. He made drawings of images seen in situ and collected some of them, which are today displayed in the Indian Museum (Kolkata), the State Museum (Lucknow) and the British Museum (London). “A detailed study of these sculptures and those preserved and worshipped in the temple of Kurkihar helped me define the characteristics of the local stylistic idiom, and to recognise it in images recovered from various other sites of Bihar and Bangladesh and beyond in numerous images which found their way into private collections in India and abroad,” she said.

Scholars believe that Kancheepuram, 76 km from Chennai, was once a prominent Buddhist centre surrounded by monasteries. Tamil epic Manimekalai says Kanchi (today’s Kancheepuram) was a place where Buddhism was nurtured in the viharas (monasteries) by the monks. In one of his accounts, Chinese traveller Xuanzang had mentioned Kancheepuram as a town scattered with monasteries. Many Buddhist scholars were associated with Kancheepuram. “Arya Deva (2nd-3rd century CE), the successor of Acharya Nagarjuna, Buddhadatta and Buddhagosha (5th century CE), the legendary Bodhidharma, who was a prince of Kanchi and reached southern China on a voyage and converted the southern Chinese Emperor Wu-Ti of Liang Dynasty to Buddhism, Dinnaga (6th century CE), an eminent Buddhist logician, Dharmapala, mentioned in the Chinese and Burmese sources, were all associated with this city,” according to UNESCO. Unfortunately, you can’t see the remains of any Buddhist viharas in Kancheepuram today. Scholars believe that the influence of Buddhism dwindled with the rise of the Bhakti movement in the region.

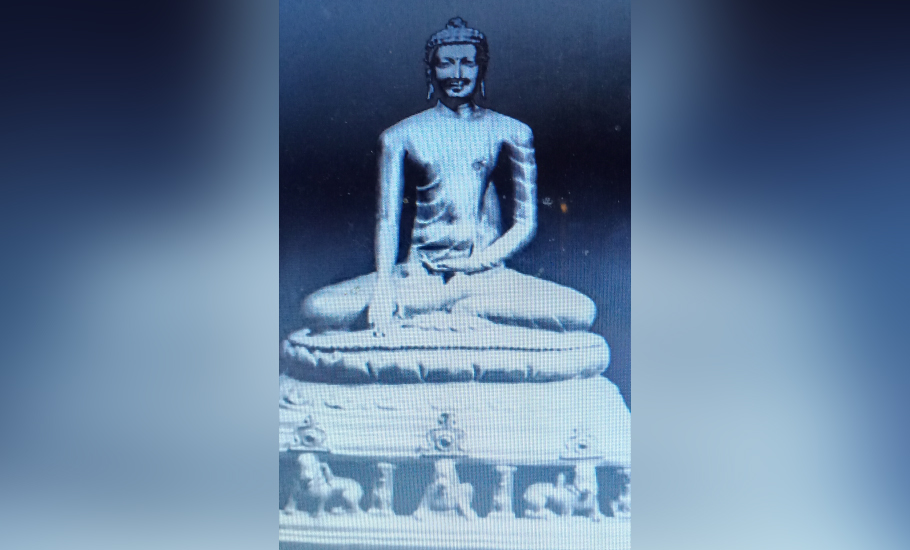

The sculptures of Kurkihar are important if one wants to study the iconography of Buddha in detail. The sculptures of Buddha have undergone drastic changes from place to place. For example, the sitting posture. “In the sitting posture of Buddha, we can make out the differences. In some sculptures, the legs are not properly crossed as they are just kept on top of the other. But at the same time, some sitting postures have the legs properly crossed as in the Padmasana pose. Two such cross-legged sculptures of seated Buddha found in Kurkihar were offered by Buddhavarman and Dharmmavarman from Kanchi,” said Claudine, who lives in Berlin, Germany.

Claudine said the stone sculptures of Buddha found in Kurkihar had different decorative motifs and ornamentation around them. The style of throne, garments, jewellery on the sculptures had incorporated elements from the south and other parts. There are differences in the ‘ushnisha’, the crown of Buddha and the symbol of enlightenment. “In the Nagapattinam style, the ‘ushnisha’ is visible clearly, but some sculptures found in Kurkihar have a flame in the place of ‘ushnisha’. This is the best example of the fusion of south and the east when it comes to art,” she said. However, a standing sculpture of Buddha, offered by Nagendravarman of Kanchi and a seated sculpture of Buddha offered by one Amrtavarman from the same region have two types of crowns. “This shows that even though the local style influenced the artists, the monks who offered the sculptures had ideas of their own,” she added.

Then why did Kurkihar lose its fame? Claudine said the production of the stone atelier was simultaneously brought practically to an end around the beginning of the10th century whereas the foundry still preserved its activities up to the end of the 11th century at least.

“In this context, the site lost the fame which it must have had in the 9th century, considering the fact that images carved in the local stylistic idiom were exported to far-away regions – and sank into oblivion, awaiting rediscovery in the 19th and 20th century,” said Claudine.