- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Gau raksha strips TN's leather industry to the bone

It is 9 am, the busiest time of the day, and Munuswamy is busy sharpening his knife at the Pernambut slaughterhouse. It is one of the four licenced slaughterhouses in Vellore where cattle (excluding cows) are killed for meat. Forty-five-year old Munuswamy is one among the many dalits in the district who eke out a livelihood by skinning cattle at the slaughterhouse. “When you skin cattle,...

It is 9 am, the busiest time of the day, and Munuswamy is busy sharpening his knife at the Pernambut slaughterhouse. It is one of the four licenced slaughterhouses in Vellore where cattle (excluding cows) are killed for meat. Forty-five-year old Munuswamy is one among the many dalits in the district who eke out a livelihood by skinning cattle at the slaughterhouse.

“When you skin cattle, you start from the tail. Only then will you be able to take out the entire hide without damaging it,” Munuswamy says as he skillfully manoeuvers his knife through a dead buffalo calf.

Munuswamy, who learnt the skill from his father, has been in the profession for the past 25 years. “We skin around five to six cattle every day. We are daily wagers. Our wages are fixed at ₹300 per day, irrespective of the number of cattle we skin,” he explains.

Earlier, the wages were higher. Five years back, when there was a steady supply of live cattle from states such as Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal, skinners like Munuswamy used to work in different slaughterhouses to supplement their earning. Today, Munuswamy is on the verge of unemployment because of a sharp decline in the transport of both live cattle and hide from northern states to Tamil Nadu over the past two years.

Sources attribute the decline in supply to gau raksha (cow protection) measures and the blanket ban on cattle slaughter in states such as Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat, after the ascension of the Modi government to power. After a series of lynchings and vigilantism by Hindutva elements in northern states, cattle suppliers have grown wary of supplying the hide of animals who died natural deaths, say sources.

How the supply chain worked

Before the curbs on cattle slaughter in the north, cattle were ferried in trucks from northern states to slaughterhouses in Tamil Nadu districts such as Vellore, Erode, Dindigul and Trichy where they were skinned. The meat was sold to butchers, and hide was bought by leather suppliers who got it processed in tanneries before selling the leather to small, medium and large leather or footwear manufacturing companies. The leather companies based in these districts were also dependent on processed and unprocessed cattle hide (mainly buffaloes, cows, bulls and calves) that came from the northern states. The hide of cattle slaughtered in Gujarat, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh was sent to Kolkata for tanning after which it was transported to Tamil Nadu via Gummidipoondi, Gudiyatham and Krishnagiri and the Tada check post in Andhra Pradesh. Unprocessed cattle hide was transported to tanneries in Vellore for processing.

Why the dependence on North Indian states? The leather derived from cattle in Tamil Nadu is far inferior compared to that from North Indian states. Experts say this is because Tamil Nadu cattle is malnourished compared to their healthy counterparts up north. “As Tamil Nadu is a drought-prone state, a majority of the bovines here are not healthy. If the cattle are affected by any disease, people brand them with hot iron. We don’t procure such animals. On the other hand, the cattle from the northern states are healthy and, hence, the leather is good,” says CM Zafarullah, secretary, South India Tanners and Dealers Association, Ranipet.

Domino effect of ‘gau raksha’

The dip in supply has had a cascading effect on the leather industry and affected the livelihood of all those who are part of the supply chain — skinners, tanners, suppliers, dealers, finished leather manufacturers (leather product companies) and exporters.

In the absence of quality hide from northern states, suppliers have to depend on locally-sourced leather, which have few takers due to its inferior quality. “The price of raw leather came down drastically after cow protection measures were enforced in North India,” says 32-year-old Dinesh Kumar, who along with his father supplies raw leather to medium size leather companies in Vellore district. He owns a godown in Ambur that is stacked, for months now, with locally-sourced raw leather, as no company is ready to buy it. “In the past, we procured hide from butchers and slaughterhouses for ₹400-₹500 and sold them to companies for ₹1,200-₹1,500. Now, if we procure leather for ₹100, we can’t tell if we’ll sell it for ₹150 or ₹50,” he rues.

Vellore’s legacy of leather

Vellore for the past many decades has been a hub of leather products due to the exceptional quality of tanning. “Traditionally, cattle have been brought from the northern states to Vellore, because the process of tanning is good here and the district still retains its legacy,” says Zafarullah.

Vellore differs according to the region — Vaniyambadi traditionally uses sheep skin, Ambur largely works with goat skin, and Ranipet on buffalo hide. “A majority of leather companies use buffalo hide from Ranipet. Buff leather (leather from bulls and buffaloes) was skinned from ‘fallen animals’, such as still-born calves, birthed in the chilly months of November and December in the northern states. Sometimes, the cattle dying of natural causes were also brought here,” he says.

In the past, leather industries in north India also got their raw materials tanned at workshops in Vellore. But over a period of time, the demand from the north declined after the emergence of newly-developed tanning facilities there, which in turn started eating into the cattle supply meant for Tamil Nadu. Despite that many traders from the north were dependent on tanneries in Vellore, until cow vigilantism stopped both orders as well as carcasses from northern states.

In 2016, the cattle in Tamil Nadu contracted foot-and-mouth disease and there were reports that many slaughterhouses had to shut shop. As per current laws, cattle can be slaughtered only after receiving a ‘fit for slaughter’ certificate from a veterinary doctor. The animals must fulfill certain conditions to get the certificate, like be permanently unfit for work or breeding due to injury or incurable disease. The restrictions on unauthorised slaughtering in shanties could be a reason for the decline in sourcing raw leather, say sources.

Dip in supply and export

The decline in supply has affected the leather export of the country. “The cow slaughter ban in Tamil Nadu, which extends to buffaloes in many states, affected the industry to a large extent. That caused a decline in the supply of cattle to Tamil Nadu, increasing leather companies’ dependence on local cattle hide,” says VN Mohamed Hussain, former scientist at the economic division of Central Leather Research Institute.

He remembers seeing 15 lorries loaded with cattle hide arriving at the SIPCOT region of Ranipet to be tanned from northern states every day, just a couple of years back. “Today, it’s difficult to see more than one or two lorries a day,” he says.

“After 2017, large companies started to import leather from countries like Germany, France, the US and Spain. The medium- and small-sized leather companies, unwilling to buy local cattle hide, started to decrease their volume of business. As a result, many tanning companies that relied on those finished leather companies are closing down,” adds Hussain.

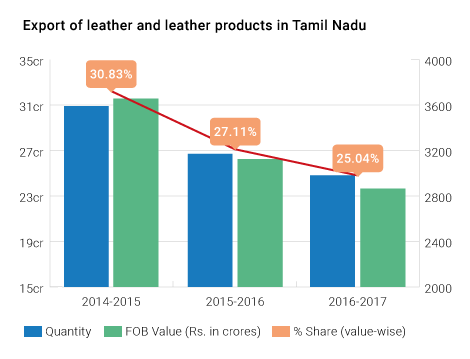

A report from Council for Leather Exports says that India’s export of finished leather has decreased from $886.39 million in 2016-2017 to $874.23 million in 2017-18. The freight onboard value of Tamil Nadu between 2014 and 2018 also shows a downward trend. “Besides cow protection, the industry was hit by demonetisation and the GST,” says Neya Sundar, district president, North Arcot District Tannery Workers Union.

TN graph

“The large companies that are in the shoe making business import leather. It is the medium and small companies that are affected. But even those companies have associations to voice their concerns. But the workers who skin the cattle are affected the most. Workers in companies get proper emoluments, whereas the skinners are part of the unorganised sector; they are left in the lurch,” he says.

“Beef is the main product, leather is a by-product. Instead of wasting the leather of dead cattle, we use it and that is the salient feature of this industry. If the government understands this, there will be a solution,” says Hussain.