- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Urlis, Chattis and Cast Iron: Traditional cookware is spicing up palatable treats

Manasvini TR remembers the piping hot, crisp dosas her grandmother would make for the kids when the family would be visiting from Bengaluru to Cuddalore in Tamil Nadu. “My grandmother’s kitchen fascinated us kids. There would be bronze and clay pots and pans. The sizzle of the cast iron tawa (griddle) when making dosas would get our mouths watering,” she reminisces. It has been over...

Manasvini TR remembers the piping hot, crisp dosas her grandmother would make for the kids when the family would be visiting from Bengaluru to Cuddalore in Tamil Nadu. “My grandmother’s kitchen fascinated us kids. There would be bronze and clay pots and pans. The sizzle of the cast iron tawa (griddle) when making dosas would get our mouths watering,” she reminisces. It has been over three decades since. Manasvini is today settled in Gurugram. In an effort to recreate the taste of her childhood for her children, she has moved to cooking with traditional cookware for the last two-odd years.

“It all started during the pandemic when I had ample time on my hands and I was motivated to try and cook rasam like my grandmother. Earlier, I would always use the pressure cooker to cook rasam. But during the pandemic I craved the taste of my grandmother’s food. I scoured online and found an eeya chombu (tin vessel). When I made rasam in it, even my 10-year-old could tell the difference. The taste seemed purer and more wholesome,” she says.

Like Manasvini, it was the craving for food like her grandmother’s that motivated Kochi-based Kaviya Cherian to quit her job and start a platform — Green Heirloom — that provides traditional cookware for the modern kitchen. With the help of her bronze uralis and meen chattis, her patrons are bringing back the lost taste and texture of dishes from jackfruit halwa to fish curry of their childhood. “I want us all to relive the tastes of our childhood,” she says.

Traditional cookware is having its moment in the limelight. And it’s not just home chefs who are enamoured by the rustic flavours, many professional chefs are also pioneering the use of age-old kitchen accompaniments. One of the leading female chefs in India, Amninder Sandhu, is well-known for setting up the first gas-free kitchen in the country and using traditional forms to cook.

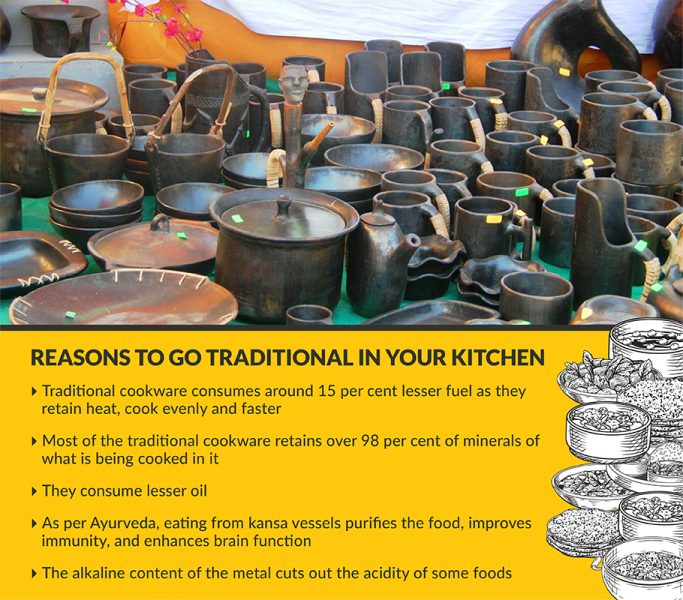

Like Sandhu, many professional kitchens are proudly using traditional utensils and cooking methods. Needless to say, silbatta (stone grinder), sigri (coal or wood-fired stoves), soapstone mortar and pestle, and more such heritage equipment are making their presence felt in the modular kitchen.

Though, the use of traditional utensils is on the rise, there is often a marked change in how it is being used in the modern day as opposed to old times. Bronze uralis, once a preferred medium to cook payasam and halwas in many households, is today a favourite of many professional kitchens for cooking meat and meat-based dishes such as biryani. The reason is that because the vessel is heavy-bottomed, it heats up evenly making it easier to cook dishes that require temperature control.

Likewise, soapstone bowls—once favoured to cook vegetables because of their evenly heating properties—today make a stylish statement as a breakfast bowl of goodness filled with cereals and fruits. Even the Manipuri Longpi bowls made of black stone and polished with clay is used as Buddha bowl in many Asian restaurants, unlike its traditional use of cooking piping hot wholesome broths.

Most patrons, who today use traditional cookware in their kitchens, claim that the overall flavour profile of the dish gets a makeover. Meenakshi Thakur, a resident of Delhi, remembers her father cooking meat in earthen pots in her hometown of Darbhanga. “When I would try to recreate the dish in my pressure cooker, I would fail miserably. I started using an iron kadai (wok) which made the dish more flavoursome. Last year on, I started using black clay uralis to cook my meats. The flavour is not the same as what my father cooked since he cooked on an open coal fire, but it is close,” she says. Meenakshi has also taken to using clay pots to set curd, which she says enhances the flavour without making the curd too sour.

Today, brands such as Green Heirloom, The Indus Valley, Essential Traditions by Kayal, Zishta, Mitti Cool, Ellementry and more have come up with a range of cookware in brass, bronze, cast iron, soapstone, longpi, earthenware to entice patrons into giving their kitchens a traditional makeover. What is equally heartening is that almost all these brands are run by young entrepreneurs. For most what started as a personal journey of going back to the roots, evolved into a longing to share their passion with others.

It’s not just recreating the taste of childhood that is making traditional cookware a big win. What is also aiding in its popularity is the many health benefits these cookware possess. Clay pots turn acidic foods alkaline, making them easier to digest. Plus, these cookware are a sustainable option because they can literally outlive you. And one can use or dispose of them without worrying about the environmental implications. The soapstone kal chatti or even Buddha bowls promise to preserve nutritional values besides adding some extra minerals to the food.

“The adoption of Western cooking practices and cookware such as the much-in-demand Teflon-coated pots and pans and non-stick utensils increase the risk of health problems such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, malnutrition, and obesity. Aluminium toxicity and nutrient breakdown have become a common problem in even the most preferred household option of pressure cooking. It is important to use of earthen cookware, clay pots and some selected metal utensils such as copper, iron, and brass,” says Anam Golandaz, Clinical Dietician, Masina Hospital, Mumbai.