- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Udupi struggling to script Srithale revival story on palm leaves

The temple town of Udupi — known to be the global headquarters of Dvaita philosophy, a dualistic interpretation of the Vedas that theorises the existence of two separate realities –abounds in stone edicts dotting temples and old structures of archaeological value. The stones have fallen into ruin and the inscribed edicts are in a shambles facing the threat of being lost forever....

The temple town of Udupi — known to be the global headquarters of Dvaita philosophy, a dualistic interpretation of the Vedas that theorises the existence of two separate realities –abounds in stone edicts dotting temples and old structures of archaeological value. The stones have fallen into ruin and the inscribed edicts are in a shambles facing the threat of being lost forever. The option of digitisation exists and also doesn’t. For, it lacks the charm of the classical form.

To preserve both the edicts and the old-world charm, some decided to go back to the centuries-old way of preserving and passing on the knowledge by putting it all on Srithale leaves. The only problem – Srithale trees too face extinction.

To tide over the problem, Udupi has undertaken efforts to save the last bastion of the ancient art of Thaale Gari (Srithale leaf) engraving from extinction.

Experts in the area turned their focus on the conservation of the Srithale tree about 15 years back in 2006-2007. Headed by the director of the Udupi-based Prachya Sanchaya (Oriental Archives) Research Centre, prof SA Krishnaiah, a team of researchers, including botanists, engravers, conservationists and activists, undertook an exercise to save ‘Srithale’ (Corypha umbraculifera), commonly known as the talipot palm.

“This is a species of palm that is native to eastern and southern India and Sri Lanka. It also grows in Cambodia, Myanmar, China, Thailand and the Andaman Islands. It is a flowering plant with the largest inflorescence in the world,” says Krishnaiah.

The threat of superstitions

So, how did a species with the world’s largest inflorescence come to face an existential threat?

The answer lies in some superstitions linked to the tree’s flowering. Srithale is mococarpic, which means it flowers only once in its lifetime averaging to about 60-80 years. The tree dies after that.

Some people believe that the flowering of the tree is followed by a severe drought. Some others believe that whenever a Srithale tree flowers, an elderly person of eminence living in the vicinity of the flowering tree passes away. To avoid the drought and death, people avoid the tree’s flowering. Called ‘avinashi’ (indestructible) in Sanskrit, Srithale trees are thus usually cut down before they flower.

“Due to some superstitions, particularly on the Coast of Karnataka, these trees are being cut down before they flower. The superstition is woven around an unfounded story that a flowering Srithale tree carries a bad omen, and the event of flowering will be followed by the death of an important elderly person living in the immediate vicinity of the tree. The number of these trees has thus dwindled drastically and no impactful conservation efforts have been made till now,” Krishnaiah told The Federal.

Srithale grows widely in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha and West Bengal. With the spread of Buddhism from India, the seeds of the tree also reached Southeast Asian countries. The earliest mention of Srithale is, however, found in Upakathas of the epic Ramayana.

“Tamil Nadu even today holds the largest numbers of Srithale trees at about 12,000. What is more important is that Srithale has a unique type of leaf. When treated with a mixture of herbs they become extremely long-lasting. The original manuscripts of Kautilya’s Arthashastra, which is engraved on Srithale leaves dating back to 314 BC, is still preserved in Oriental Institute of Research (ORI). I do not think any modern storage device, technique or instrument will last that long. So, if we are serious about saving the art of palm leaf engraving, conservation and protection of Srithale tree gains prominence,” Krishnaiah says.

Etched on a leaf

A young researcher, Musica Supriya, has taken up showcasing the uses of Srithale Gari by engraving various coloured picture series drawing from different episodes mentioned in different epics. Like her, many youngsters, are working on different aspects of the campaign to save the tree.

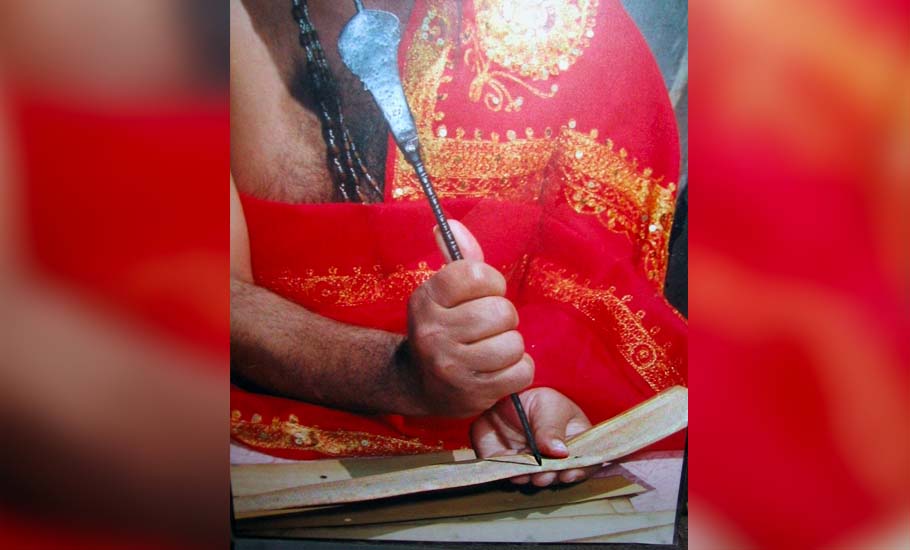

Subhas Naik, a young archaeology student, says, “The palm leaf engraving is an intricate art. When you engrave on the processed Srithale leaves, you do not get to see anything. Only when you dip it into a especially prepared charcoal liquid, the engraving appears. The instrument we use to engrave is made of metal and the pressure we use on the leaves should be exactly the same for every letter. This will help in conserving the lifespan of the document,” Naik says.

Researchers say sixty-seven per cent of the available documents engraved on the Srithale leaves are in Sanskrit, 25 per cent are in other Indian languages, including the Pancha Dravida bhashas — Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu and Tulu — and 8 per cent in Arabic and Tibetan.

Researchers point to thousands of palm leaf inscriptions that include epics, documentation of visits of foreign philosophers and even the original manuscripts of Arthashastra, Upanishads and Puranas and historical events have been preserved for thousands of years on palm leaf inscriptions. Palm leaf inscriptions could be best suited for preserving writing in time capsules, say conservationists.

With no funding and little awareness, the art form is gasping for life. On the one hand, the Srithale tree is facing extinction. On the other, the commercial interest in Srithale Gari engraving is dwindling. New technology like screen printing on the leaves has posed a whole new threat to the art form.

“I am using up all my family earnings and savings for this conservation. But how long?” asks prof Krishnaiah. His institution has knocked on every door and offered lessons in leaf engraving in universities, colleges and institutes but has met only with cold responses.

Belonging to the palm family of trees, Srithale is considered the ‘princess’ of its species.

“It is a fabulous looking tree with a large canopy that can easily hold at least 20 people under its shade. It gives over 2 lakh or more seeds in about 60 years of its lifetime as it is rich in flower stimulating hormones. The tree, however, is grows very slowly. Unlike the other palm trees, it does not give fruits, but only nuts, which are nothing but seeds. Each of its enormous leaves may form a semicircle of up to 16-feet in diameter and cover an area of about 200 square feet on the ground. However, the deep physiology of this tree has not been fully studied as many of its botanical features are complex and beyond our imagination” says Dr Arvind Hebbar, a senior botanist.

Put to use

Conservationists have so far succeeded in preventing felling of Srithale trees in three villages of Udupi and harvested the seeds for propagation of the species.

The Karnataka forest department has some enthusiastic officers at range and divisional levels who have wide-ranging knowledge about the importance of Srithale in relation to the eco-cultural aspect.

Ashok Bhat, assistant conservator of forests, Honnavar in Uttara Kannada district in Karnataka says, “Srithale is very majestic in appearance and is seen on the western slopes of the Western Ghat sporadically. Their main propagators are birds, especially bats. They pluck the nuts that have a juicy cover and travel distances and drop the seeds. There are other large birds also that propagate the seed. But there has never been any human effort to plant saplings or sow seeds, though the tree is useful to humans in myriad ways right from housing to nutrition and conserving culture.”

The late Manjunath Shetty, deputy conservator of forests of Kundapur subdivision in Udupi district, had made efforts to grow Srithale as forest plantation. His work has yielded results in many places across the Kundapur forest division.

To create awareness about the importance of protecting the species, researchers at Prachya Sanchaya (Oriental Archives) Research Centre have collated 37 different uses of the Srithale tree. “One of the main uses is that of sago (rounded natural starch), which has medicinal properties. Ganji (porridge) made out of sago has regenerative health benefits for patients with several types of fevers and stomach disorders,” says Katpady Sathishchandra, a traditional medicine practitioner.

Powdered sago kept in airtight containers can be used after years and has high nutritional qualities. Its thick and strong roots help in preventing topsoil erosion on the slopes and its wide canopy offers nesting places for large birds. Even today, many huts in the tribal areas along the deep Western Ghats have their roofing material produced from Srithale leaves. The agricultural workers in the coastal areas of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Goa make gorabu (a hood big enough to cover their entire body) out of the leaves of Srithale tree to shield themselves from rains during monsoons when they are busy working in the fields.

Srithale is also part of the ‘Devara Kaadu’ (a kind of reserve green patch) in Naaga Banas, Daiva Sthaanas that features in the ritualistic theatre and folk and performing arts centres in all southern states. At Ananthapadmanabha Swamy temple in Kerala, the temple trust promotes the planting of Srithale trees.

In the 9th century, Pallava King Nandi Varma had ordered the planting of Srithale trees around the Mahadeva temple of Thirunattavalli in Tamil Nadu and many trees of that lineage exist around the temple even today. In Tulu Naadu, stretching from Chandragiri river to Barkuru river, people honour the former royal family members with large umbrellas, hand-woven with Srithale leaves.

Senior professor of Forestry College in Sirsi Uttara Kannada in Karnataka, Vasudeva R, is of the opinion that Srithale should be propagated with human effort, by planting, nurturing and growing.

“Presently, only bats, civet cats and squirrels propagate the seeds of this great tree. We must make efforts to grow them in biological, national, zoological parks or wherever their survival is not threatened. They should be allowed to grow, reach their primacy and die naturally. Such a protected environment will give conservationists a safe area to grow and conserve them. Allowing Srithale to survive on its own in the wild is not the right approach to conserve it.”

Emulating Sundarlal Bahuguna’s Chipko Andolan (appiko in Kannada), the people in Udupi, Moodbidri and Karkala have launched a special drive, Voppiko (accept). Charukirti Bhattaraka Panditacharyavarya Swamiji of Moodbidri Jaina mutt says, “Accept Srithale tree as your heritage.”