- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Truth be told, masks expose the hidden face

When the world goes back to being 'normal' (if ever), perhaps we will have mastered the art of being vulnerable, perhaps we will have understood that nothing lasts for ever, that power crumbles easily, that life is fragile, that love is precious.

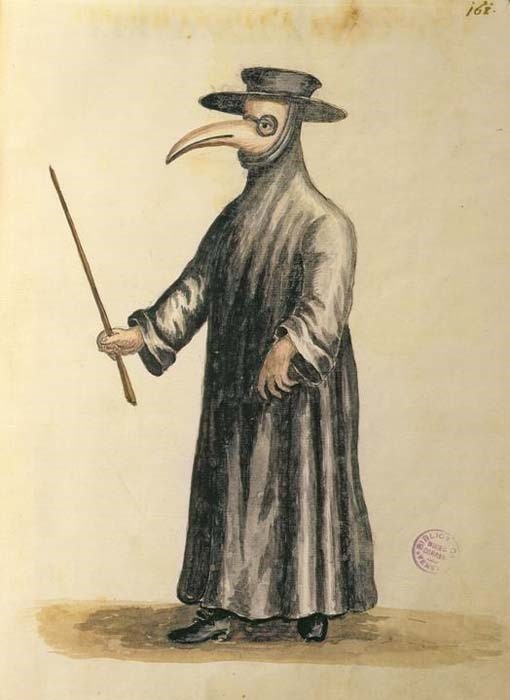

Some time during the early 17th century, when numerous plagues were raging across Europe, hooded figures wearing beaked masks came to be associated with sure death. These figures were actually plague doctors, who were clothed in their version of the hazmat suit. Although full robes weren’t uncommon, it is the mask with glasses and a top hat, that gave it all its sinister associations. Jan...

Some time during the early 17th century, when numerous plagues were raging across Europe, hooded figures wearing beaked masks came to be associated with sure death. These figures were actually plague doctors, who were clothed in their version of the hazmat suit. Although full robes weren’t uncommon, it is the mask with glasses and a top hat, that gave it all its sinister associations.

Charles De Lorme, the physician to the European royals, is credited with inventing that infamous outfit and mask with a beak, which held a mixture of herbs called theriac (an antidote to poison) and was supposed to help the doctor counter miasma (noxious air emanating from organic sources, once thought to cause diseases). Today, it is sported by many during Halloween and other carnivals.

The many faces of the mask

A mask for protection turning into an object of masquerade is the kind of transition or transformation that can be found in the cultural biographies of many material objects. Of increasing interest to social scientists is the way human and object histories intersect with and inform each other.

A perfect case in point is the face mask most of us are sporting at this time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps a decade or two later, when the dreadful memories of this time have begun to fade, a simple surgical mask will also become an amusing prop for a costume — a grim reminder of a global tragedy, worn lightly. But at present, its singular function i.e. protection from the virus, remains in sharp focus.

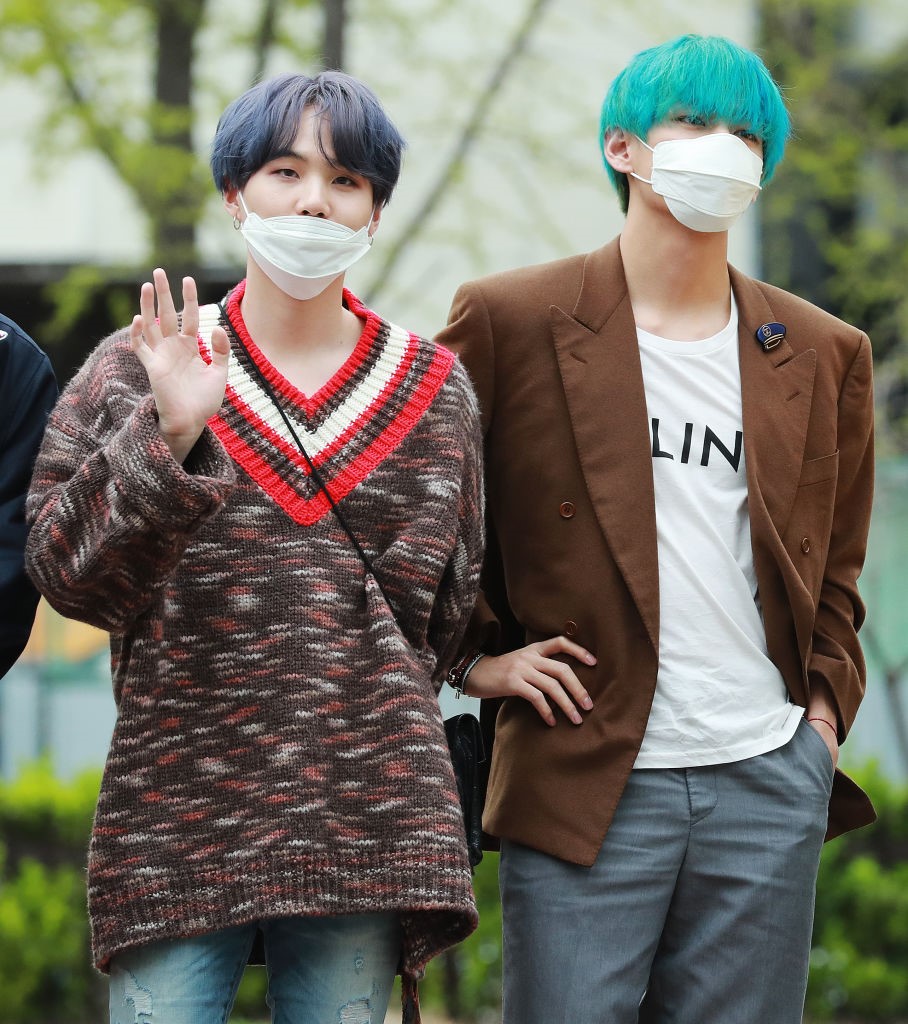

Even so, the humble face mask is not devoid of cultural weight. While many western countries debated over the need for face masks and paid a heavy price for their reluctance, Asian nations took to it pretty quickly. It has been surmised that for Asians, with their recent histories of SARS, swine flu and other respiratory disease outbreaks, wearing a mask in public has become commonplace. It not just offers protection against external infection, but also avoids the wearer from spreading an infection, if they’re ill.

In a community-centric culture, this is a responsible thing to do, and is both, expected and respected. In fact, mask-wearing is now so normalised in countries like China, Japan and Korea that it is often sported by celebrities as a fashion accessory. Closer home, covering one’s face to avoid sunstrokes or ashtma attacks due to heat and pollution is also common.

In the individual-centric culture of the West on the other hand, wearing a mask has been seen as a sign of being diseased and is therefore, stigmatised. As the West learns to put a mask on it, we may take some time to ponder upon other cultural imports of masks, like this popular Wildean quote: “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth.”

A Heist of Meanings

Hiding behind Salvador Dali masks, the Professor and his crew are trying to tell many such truths about the system. The reference is to the Spanish Netflix superhit series Money Heist, which returned recently with its fourth season. What with the lockdown, it caused a predictable social media flurry among its community of fans, and unprecedented viewership.

As the name suggests, the show is about a gang of robbers engaging in a heist. The protagonist called The Professor and his team members, who go by city names, use anonymity not just to loot mints and banks but also to challenge the capitalist state. They represent the masses offering resistance, and do so with clever plans, guns, red jumpsuits and Dali masks.

The choice of Dali’s face for a mask by the show’s makers is not incidental. Apart from being eccentric and hence memorable, a Spanish — indeed a global — icon, Dali was also a known for his strong anti-capitalist stand. As the show progresses, the robbers are transformed into Robin Hoodesque characters in the public’s eyes, who then, come out in support, sporting hundreds of Dali masks.

A similar phenomenon occurs in the 2019 film, Joker, when hundreds of supporters paint their faces like the protagonist to make a statement. A mask used for anonymity by robbers becoming a tool of mobilisation and a symbol of mass resistance is yet another example of the functional and cultural transformation of an object. But whatever the change in its associated values, the primary power of the object in question remains unchanged — concealment.

Unmasking ourselves

A mask as a shield that hides the face partially or completely becomes a barrier between the wearer and the world. It lowers one’s inhibitions and gives one a sense of strength and security. Because anonymity de-individualises, it liberates people, and gives the weakest amongst us a voice.

On the downside, it may encourage one to behave in ways they may otherwise not behave in, and not feel personally responsible for their actions. The masks of anonymous social media accounts are only too glaring examples of this. But it is important to not lose sight of the humanity of these narratives too. After all, the wearer of any mask — no matter how ugly or terrifying — is a human being trying to tell their truth.

As we learn to live with masks on, this time may perhaps also be opportune to learn to take our other masks off. When the world goes back to being ‘normal’ (if ever), perhaps we will have mastered the art of being vulnerable, perhaps we will have understood that nothing lasts for ever, that power crumbles easily, that life is fragile, that love is precious. And perhaps, we will never need to wear a mask ever again.

(The writer is a scholar of Interfaith Studies at the University of Wales. She researches and writes about Indian culture, history and mythology)