- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Troubled waters: Rampant illegal sand-mining creates death traps in Krishna river

V Nagesh and his four college friends—M Harish, K Lokesh, P Gopi Reddy and K Hari Gopal—were on a casual swimming session in Krishna river when they met with a cruel twist of fate. The youths, all in their 20s, slipped into the deep water and drowned in a tragic accident that took place in Gidugu village of Andhra Pradesh on August 16, 2016. Exactly two years later, in August 2018,...

V Nagesh and his four college friends—M Harish, K Lokesh, P Gopi Reddy and K Hari Gopal—were on a casual swimming session in Krishna river when they met with a cruel twist of fate. The youths, all in their 20s, slipped into the deep water and drowned in a tragic accident that took place in Gidugu village of Andhra Pradesh on August 16, 2016.

Exactly two years later, in August 2018, four students met the same fate after they ventured into the swollen river at Gundimeda in Guntur district.

In the same year, in May, two members of a family—a woman and her daughter—lost their lives after their boat collided with a dredger boat used for mining.

All these incidents are connected by one key factor—deep pits formed by mining of sand from the river bed.

Sand can be mined through dredging—excavation carried out under water—or when the river bed is dry. Both can form deep craters. These deep craters become invisible when it rains or water is released from a dam. Anyone mistaking it as a shallow river could chance upon these craters as they can’t make out the depth from the outside and drown, if they are taken by surprise or don’t know how to swim.

“You may know about the five college students drowning as a standalone incident but there are hundred such cases which didn’t make it to the news,” Anumolu Gandhi, a prominent environmentalist and one of the petitioners in the National Green Tribunal (NGT) case filed against illegal sand mining in Krishna river, tells The Federal.

“In fact, we had studied the Pavitra Sangamam boat mishap that claimed 21 lives in 2017 where illegal sand mining was one of the main reasons for the tragedy,” Gandhi stated.

As per reports most of the mining is illegal and done in secret, leaving gaping holes in the river bed that eventually pull anything that flows nearby.

Further, the lack of knowledge of the deep pits formed by unplanned mining makes the search operation difficult.

Magsaysay Award winner and Water Man of India Rajendra Singh too, while addressing a press conference after the boat mishap, had blamed sand mining for the tragedy. He said whirlpools were being formed due to the practice, which make it difficult for a boat to move once it is stuck.

“Sand mining causes whirlpools and when your boat gets stuck in one of these, nobody can save it. What is shocking is that despite us highlighting it several times, illegal sand mining continues and if it goes on like this, more people will die,” Singh had said.

Drowning cases on the rise

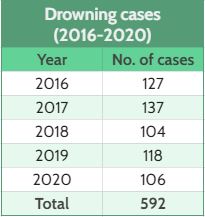

According to Vijayawada’s City Crime Records Bureau (CCRB), between 2016 and 2020, a total of 592 cases of deaths due to drowning were reported. Of these, 84 percent were accidental drowning cases, with the remaining ones being suicides.

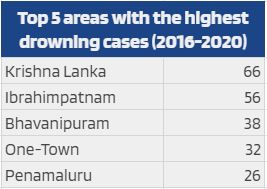

The top five areas with the highest drowning cases are adjacent to the banks of the Krishna river, with Krishna Lanka, a downstream area, topping the list with 66 deaths between 2016 and 2020. The second on the list with highest drowning cases is Ibrahimpatnam, an upstream area, with 56 deaths, followed by Bhavanipuram, One-Town and Penamaluru.

Pit report

In 2019, District Collector Md Imtiaz had ordered a departmental inquiry after several complaints of activities associated with illegal sand mining in the downstream of Krishna river were received. During an inspection, revenue officials had in fact found bulldozers excavating sand from the river.

Several areas in Krishna district including Ibrahimpatnam, Penamaluru (both in the list of top five areas for accidental drowning), Nandigama, Kanchikacharla, Chandarlapadu, Challapalli, Pamarru, Avanigadda mandals, Ghantasala, Jaggaiahpet, and Thotlavalluru have been reported as spots for rampant sand mining.

Between 2016 and 2018, police and locals rescued 106 persons from drowning across Vijayawada Commissionerate limits. While data showed that 19 of them happened to be suicide attempts, the remaining were accidental drowning cases.

Locals as well as officials have claimed that some areas have sand pits as deep as 30–40 meters.

“Some pits are deep enough to hide two palm trees one on top of the other,” a fisherman was quoted by The New Indian Express in a report.

“Heavy mining has been happening all along the river bed here. Excavation surged after the (then Chandrababu Naidu’s) state government’s decision to supply free sand. And the pits have gotten deeper and deeper, some going down to 40 m,” an employee of the District Rural Development Agency was quoted in the report.

Head Constable Nageshwar Rao, who has been serving at the Tadepalli check-post near Prakasam Barrage for the past five years, was among a handful of cops to earn accolades for rescuing more than 100 people from either committing suicides or drowning accidentally. Rao says there were some “naturally formed” sand pits near the railway bridge that resulted in the deaths of a few youngsters.

“Once three people died and more recently, one youth from Vijayawada died while swimming in that particular area,” he tells The Federal.

He, however, added that some pits that were formed due to mining may have been rectified due to heavy rains and floods in the recent past.

“As far as I know, the sand pits due to illegal sand mining exist at the fishing area, way beyond the upstream region, but there hasn’t been any major drowning incident in that place as heavy rains and floods must have rectified the pits,” he says.

Rampant violation

The Chennai bench of NGT in 2016 had banned use of heavy machines like poclains and dredging machines for sand mining as well as use of heavy vehicles for transportation of sand. However, not much has changed since, with mining continuing as before. Transportation too takes place unabated using trucks, mini trucks, and passenger auto-rickshaws.

In November last year, the Chandarlapadu police and Special Enforcement Bureau (SEB) jointly conducted raids on the river bank and seized ten tractors, two earth-movers and 400 tonnes of sand, which was being transported illegally to Hyderabad.

While there are no official figures available for the amount of sand mined illegally, news reports from 2016 suggest that 2,000 truckloads of sand were transported to Hyderabad every day from the beds of Krishna, Godavari and others.

Water salinity rises

According to the geological survey of India (GSI), river bed mining leads to immense alterations to the physical characteristics of river as well as riverbed.

It is perhaps due to these “alterations” that around 73 spots near Krishna river and canal have been marked as danger-zones. A danger-zone along a river is usually a spot that is life-threatening.

Gandhi explained that other ill-effects of illegal sand mining include “increase of saline water in the ground water table”.

“A few years ago, there was no scarcity of drinking water in Nagayalanka but today, because of the increase in salination due to mining, it is not available even in Pedana which is far away from the sea,” he said.

Flip-flops

Based on a report submitted by an expert committee, the NGT in 2019 had slapped a fine of ₹100 crore on the AP government for allowing sand mining without environmental clearance.

After this, the Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP) came to power promising an environment-friendly government and even slammed Naidu for getting fined for illegal sand mining.

However, in June 2019, the same government took a contrasting stance and countered the expert committee’s report saying that ‘no illegal sand mining took place in the upstream of Prakasam Barrage’ and that only desilting action took place.

Later, the Supreme Court stayed the NGT order. The NGT then expressed dissatisfaction over the state government’s submissions and it once again constituted an independent committee to undertake assessment on the illegal sand mining. This time the committee supported the state government’s report and concluded that ‘judicious desilting activity may not have serious impacts on flora and fauna’.

“All of us who petitioned against the illegal sand mining were shocked by the brazen contrasting report. It indicated that all political parties have joined hands including YSRCP and BJP. The committee’s report needs to be challenged but after fighting for all these years and seeing the result, I didn’t have the strength to continue the fight,” Gandhi said.