- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

There’s no stopping these women mountaineers scaling the Everest

Women are better suited for mountaineering physiologically due to their greater natural endurance, and there is no stopping them from scaling the Mount Everest.

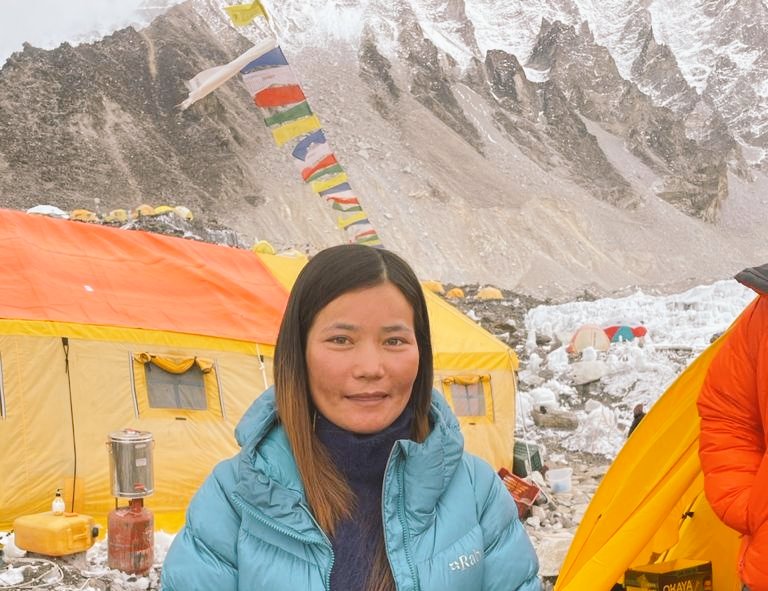

For Sikkim’s 36-year-old Manita Pradhan, climbing Mount Everest has always been a dream—but incredibly difficult. Caught by gale-force winds and heavy snow caused by cyclones, Yaas and Tautkae, her trip from the base camp was thwarted twice. “In my first attempt, I returned from Camp 3. The second time, I turned back from Yellow Band,” Manita recalls. Yellow band—a steep,...

For Sikkim’s 36-year-old Manita Pradhan, climbing Mount Everest has always been a dream—but incredibly difficult. Caught by gale-force winds and heavy snow caused by cyclones, Yaas and Tautkae, her trip from the base camp was thwarted twice.

“In my first attempt, I returned from Camp 3. The second time, I turned back from Yellow Band,” Manita recalls. Yellow band—a steep, pale yellow-brown limestone rock—is the first rock a climber touches enroute the Everest.

Finally, after climbing nine straight hours from Camp 4—the final camp on the Nepal side—she reached the summit on June 1 at 5 am.

Once she reached the top of the 8850-metre peak, she was flooded with mixed emotions of joy, relief and godly reverence. After all, she had been trying for 10–12 years and it had become difficult for her to afford travel.

“I cried with joy. Saagarmatha ne bulaya tha naa. Main Everest pahuch gayi,” she says. In her words, she meant she only obeyed the call of Goddess Sagarmatha, the Nepali name for the deity residing at the top of Everest.

Rise of women

Manita was part of the 12-member team of Everest Mastiff Expedition that set out to conquer the four soaring peaks of Mt Pumori, Mt Lhotse, Mt Everest and Mt Nuptse, all standing close to each other.

Of the 12 members, six were women, a sign that the gender gap in the male-dominated sport of mountaineering is shrinking.

The 2019 tourism records released by the Nepal Department of Tourism shows that India registered 15 successful women climbers, trailing China which led with 42 climbers. A year before, the 2018 Nepal data records show that India posted 13 women climbers, clearly being the second country with most women climbers.

Not to mention, Manita scaled the Everest at a time when the devastating second wave of Covid-19 zipped through India, nearing over 2 lakh cases. To everyone’s surprise, the pandemic didn’t spare the world’s highest point too.

“Out of 152 summits this year, around 30–35 climbers tested positive,” says Rajendra Ramtel who runs an expedition company, the World Himalayan Destination, in Nepal.

Manita tells The Federal that she was barred from walking from one camp to another to follow strict social-distancing rules enforced by the sherpas.

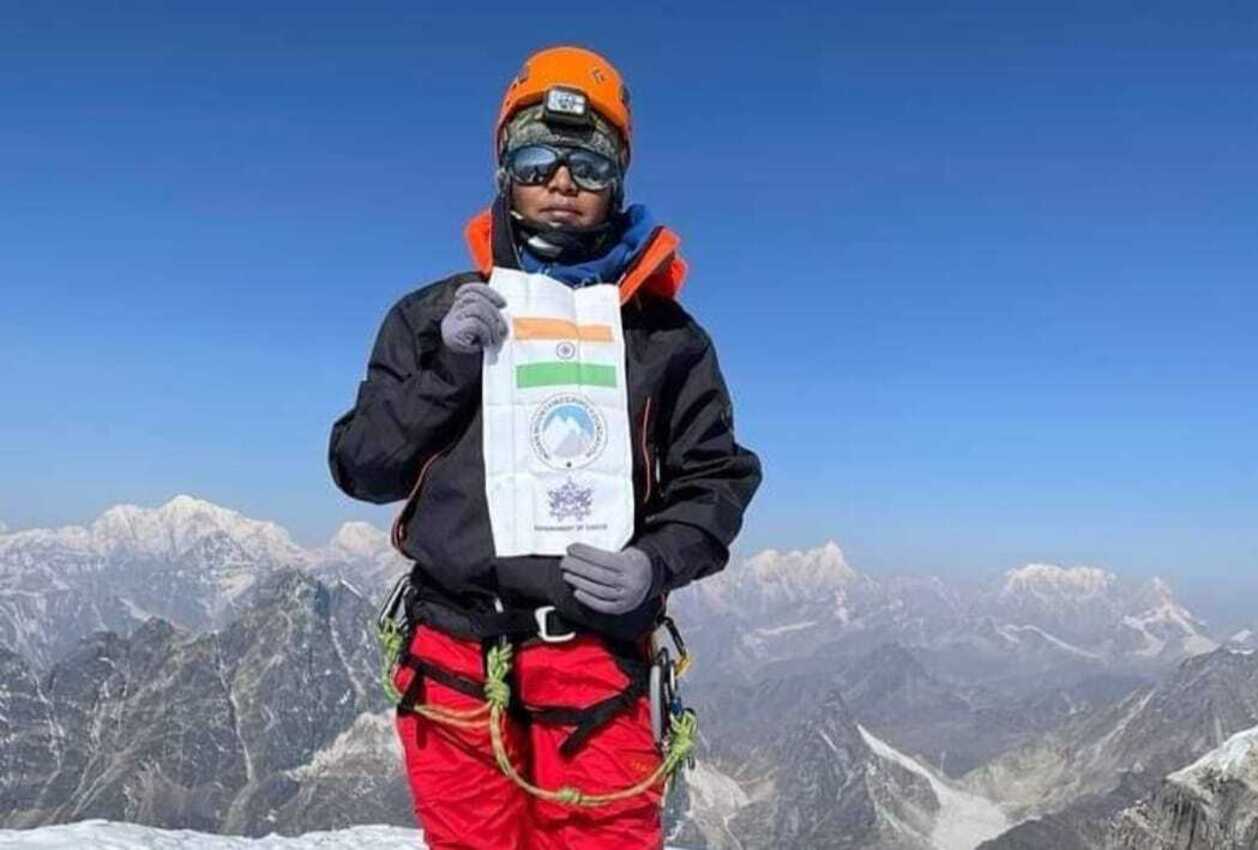

Another mountaineer from Arunachal Pradesh, 37-year-old Tashi Yangjom, almost escaped coronavirus when a fellow climber tested positive while rotating camps for acclimatisation.

Tashi was lucky to have perfect weather for the summit, with no potential bottleneck. She summited Everest on May 11 at 6 am, the moment she realised there was enough sun for her summit picture.

“I waited in the dark at the Hillary Step for 30 minutes for the sun to appear,” she says. The Hillary step is a 12-metre rocky face below the summit, and one of the trickiest parts of the Nepal-side Everest route.

At the top, Tashi reckoned climbers had died on the descent down or soon after summiting. Descending hastily, she noticed three lifeless bodies revealed by the intense sunlight. But she couldn’t do anything, as any other climber who acknowledges the risky and expensive task of retrieving bodies from such harsh and frigid heights.

The rigours involved in mountaineering

Tashi’s parents let her try mountaineering after hemming and hawing for a year. The newly opened National Institute of Mountaineering and Allied Sports at Dirang, Arunachal was on the lookout for a female instructor. Tashi took a chance, and she excelled.

In 2016, she completed the Basic Mountaineering Course fully sponsored by the Institute. Slowly, her interest evolved into a passion, and she pursued the advanced courses—with the Institute paying half the fees—until she became an instructor.

Today, she teaches trainees to run lifting weights as high as 15 kg, trekking, rock climbing–even pushing them to climb natural ice formations such as the 6,858-metre Gorichen peak, the highest point in Arunachal Pradesh.

She found a way to replicate the physical and mental challenges faced by a climber through her work. “The institute runs several climbing courses all year round. The only respite from work is during the months of June and July. I tell you… the best way to prepare for mountaineering is by becoming an instructor,” Tashi puts it.

Manita too took a similar path, starting as a freelance climbing instructor at the Indian Himalayan Centre for Adventure and Ecotourism in Chemchey, South Sikkim. Except she was enlisted for the Everest Mastiff Expedition, spearheaded by the Indian Mountaineering Foundation, out of 565 volunteers from across India.

She had to prove her mettle in four selection phases—from running with loaded backpacks in jungles to climbing Mount Trishul (7,120 metres) in the last round.

Ranging from lower incidences of types of altitude sickness like High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) to equal incidences of High-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) compared to their male counterparts, there are reasons to believe women are better climbers.

“Women are better suited for mountaineering physiologically due to their greater natural endurance,” says Amit Choudhury, who heads the IMF’s Mountaineering Steering Committee. Despite such indisputable facts, fewer women opt for mountaineering for the lack of support or resources.

Casual sexism in female-climbing

A window into the world of female climbers exposes bias against women on expeditions, persisting till today.

Tashi Yangjom became the first woman to climb Everest this season. Tashi is grateful to her male instructors who played a crucial role in her success.

Nevertheless, she had been subject to her peers dragging her down from mountaineering claiming periods signal bad weather. “They go on ‘mausam kharab hain…” You shouldn’t blame a normal function in a woman’s body, right?” Tashi stresses.

Sadly, the notion of women being inferior strength-wise during high-altitude mountaineering still lingers in the minds of male climbers. Aspiring climber Sabita Mahato–who was let go in the fourth round of the 2019 Everest Mastiff selection round–has a story to tell. During a training exercise, she sensed guys undercutting females while fixing ropes in climbing routes.

Thanks to the intervention of her instructors, her male climbers realised if they had to work as a team, they could not treat women any differently. In the ever-more fight for strength vs weakness, women had internalised the idea that they had to be tough to climb.

“Now it all comes down to the mental fortitude you possess in such climbs,” explains Manita.

Ask Manita and Tashi about their climbing role models, they list Anshu Jamsenpa without a second thought. Their reason being she summited Everest five times despite being a mother of two children.

But Anshu repetitively was chastised for being too ambitious, when male explorers are almost never asked whether it’s okay to leave their children behind. “You are a woman, a mother. Your place belongs at home. You won’t be able to climb next time…. But I always prove them wrong,” Anshu Jamsenpa laughs off.

Financial hurdles

The cost of an Everest expedition is exceptionally high, where each person has to pay a whopping Rs 25-Rs 30 lakhs. For climbers from socially and financially disadvantaged backgrounds, securing sponsors becomes important to climb Everest.

Both Manita and Tashi’s expedition were sponsored by the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports; Tashi says she received additional assistance from the Arunachal Chief Minister Pema Khandu for her trip. In recent times, Everest bears witness to a trail of rich novice climbers pocketing heavy sums to earn fame by climbing Everest, with Sherpas doing all the work.

“Everest climbing has become a tourist activity. It’s like going to see the humpback whales or diving with the sharks, and nowadays going to space on a paid space trip”, points out Amit Choudhury, the IMF member.

This trophy hunting weeds out climbers with demonstrated accomplishments such as Sabita Mahato, who has climbed over 5-6 highest peaks in India to her credit. Sabita belongs to a lower middle class family–her father is a fish seller.

Four-five years have passed since Sabita requested sponsorship from the Bihar Chief Minister and the Prime Minister but to no avail. “I am still fighting for an Everest sponsorship”, Sabita sighs. As for private sponsors, they look for a dash of creativity beyond excellent climbing skills.

“Over the years, many financially distressed folks managed to raise money for their climb sponsored by either publishers of their books, or agencies responsible for their speaking tours or films alike”, adds Amit Choudhury.

To declare climbing Everest is easy just because commercial climbing operations enable the wealthy and inexperienced clients sets a negative tone. Usually, the unqualified climbers lead to deadly traffic jams on Everest, as they cannot catch up with the Sherpas.

“These clients give Everest a bad name. Rather, only climbers selected on the basis of a national-level undertaking should be allowed”, reasons Sabita.