- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The women of Bengaluru slums who fought Covid and family’s hunger

It’s 4 am and pitch dark in India’s IT hub Bengaluru. Baby A, a 37-year-old mother, from the city’s Gautam Nagar slum, is up and hastening to finish her household chores before she heads out for work at 9 am. “It’s my daily routine, except for Sundays, since August 2020, when I took up the work of a Covid-19 healthcare volunteer,” says Baby, a Dalit woman. On the ground floor of...

It’s 4 am and pitch dark in India’s IT hub Bengaluru. Baby A, a 37-year-old mother, from the city’s Gautam Nagar slum, is up and hastening to finish her household chores before she heads out for work at 9 am. “It’s my daily routine, except for Sundays, since August 2020, when I took up the work of a Covid-19 healthcare volunteer,” says Baby, a Dalit woman.

On the ground floor of the dilapidated building where Baby stays, lives Shalini S (19) with her family. After clearing her class 12 board exams in 2020, Shalini too has been working as a Covid-19 healthcare volunteer.

While Shalini is almost 20 years younger than her neighbour Baby, it’s their economic condition that forced both of them to earn their livelihood for the first time in life. Shalini, who is also a Dalit, discontinued education to feed her family. Her mother has been bedridden for several years because of severe diabetes. Her younger brother is studying and her father, a carpenter, does not have work since the pandemic ravaged the world in 2020.

“If I don’t work and earn, my family will go hungry,” says Shalini. Standing next to Shalini, a hesitant Baby narrates her woes. Her husband, who too is a carpenter, stopped getting work since lockdown was first imposed in March 2020. “Coronavirus has changed everything. There is no work for men. We have no money. So, we women are working to feed our families and send children to schools,” Baby says.

Stories of Baby and Shalini echo across hundreds of slums of Bengaluru, the capital city of Karnataka. It is hunger and deprivation in the wake of coronavirus that has forced poor Dalit and Muslim women to come out of their houses and work as Covid-19 healthcare volunteers to eke out a living. It is also ironic that the virus that has shattered their lives has given them an opportunity to earn their living.

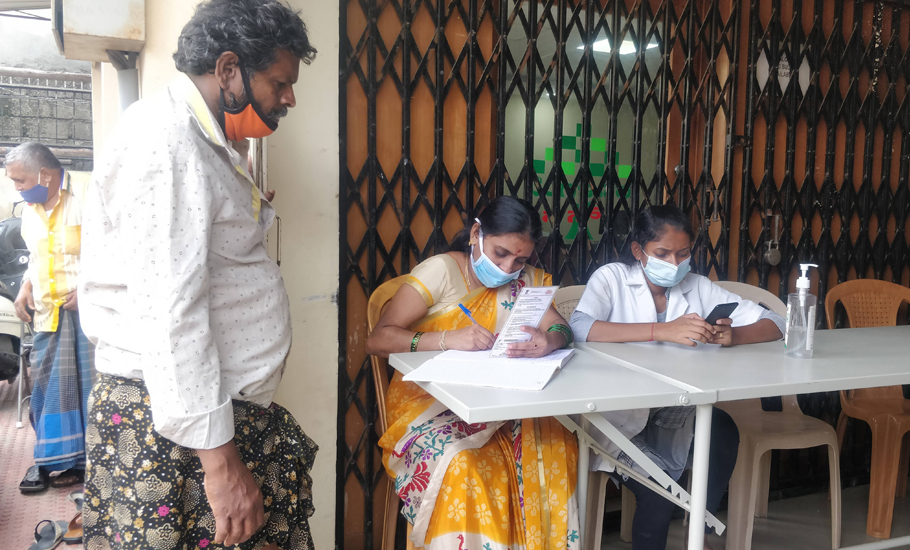

The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike, or BBMP, the municipal corporation of Bengaluru, has engaged the services of an estimated 50,000 women from the city’s slums at various points in time during the pandemic. These women – recruited as Covid-19 healthcare volunteers with the help of BBMP’s 450 NGO partners – work across 760 slums. Most of them started working from 2020 to conduct coronavirus-related sensitisation, testing, isolation and medical care of slum-dwellers. Now, these volunteers have become the driving force on the ground in the government’s vaccination drive against coronavirus among the disadvantaged population.

Explaining the job profile of healthcare volunteers, also called help-desk members, Pradip R, medical officer of the urban primary health centre in Subhash Nagar ward, said the women were the first line of defence against coronavirus. “Since the beginning of the pandemic, they did a door-to-door survey of households and listed all family members in their designated areas. They explained to the slum-dwellers what coronavirus is and what measures need to be taken to remain safe. They are responsible for getting symptomatic patients tested and isolated. Because of these women, slum-dwellers have come out for vaccination. They are a huge help for all medical professionals as they bring people to healthcare centres,” adds Pradip. The medical officer clarified that healthcare volunteers were not medical or paramedical professionals but were linkages between the poor to healthcare facilities.

First job

For most women healthcare volunteers, it is their first job. It was during the peak of the first wave of the pandemic, Baby took up her first job. All these years, Baby—who cleared her class 12 two decades ago—was busy raising her two children and doing household chores as her husband provided the finances. Things changed dramatically in her life in 2020. From a homemaker to a breadwinner, it was quite a journey for the 37-year-old.

“It was a scary decision. I was afraid of contracting the virus. I am still scared but a little less as I have been fully vaccinated. But I have no option. I have to feed my family,” said Baby. Today, she earns Rs 12,000 a month. It helps Baby run her house and provide education to her two school-going children. The 37-year-old healthcare volunteer is assigned to look after 250 households in Swatantra Nagar slum, around one kilometre from her house.

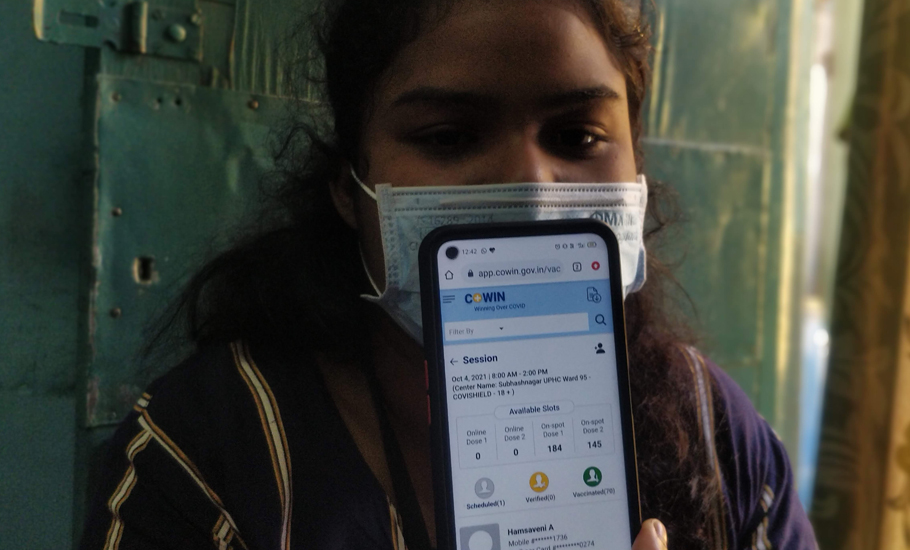

Before starting her job, she was trained by the Centre for Advocacy and Research, an NGO partner of the BBMP. After a door-to-door survey of 250 households, Baby has been helping the residents in testing, hospital visits, medical care and vaccination. Her work involves a lot of coordination with doctors, nurses and vaccinators at the public health centre of her locality. She also helps people get their names registered on CoWIN vaccinator app. Her usual workday starts at 9 am and ends at 6 pm. When coronavirus cases rose exponentially during the first and the second waves, she worked till 8 pm without any holidays.

Rehana M (27) from Ramachandrapuram slum is working as a healthcare volunteer for the last eight months. With two children, she and her husband, a vegetable vendor, found it difficult to run their household. “During lockdowns, my husband had no income. Now, he earns very little and that is why I work,” she said. Rehana added that she always liked helping people in distress. “I know I am doing samaj seva (social work) by helping people keep themselves safe from coronavirus. But there is no one to help poor women like me and my neighbours in these difficult times.”

Rehana’s lament comes from the fact that while the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has done massive campaign eulogising the valour and dedication of “corona warriors”—a term coined for India’s healthcare workers—on the ground the ancillary healthcare workers—like hospital ward boys, sanitation workers, lab assistants and ambulance drivers, to name a few—have suffered a lot. Many of them contracted coronavirus during work and died across the country, the data for which is not available.

A Right to Information query on the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths among health workers sent to the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Directorate General of Health Services and National Centre for Disease Control, was returned with the noting that “the desired information is not available with this office”.

State apathy

The healthcare volunteers get Rs 10,000 to Rs 12,000 per month. While it is a paltry amount, the regular remuneration helps the women run their households. Despite the risk involved with the job, several volunteers told The Federal, except for masks and gloves, they never got any personal protective equipment kits.

Recruiting women from slums to work as healthcare volunteers in their communities have “hugely benefitted the government’s Covid-19 health response work”, said Sushil Kumar Ichini, vaccination nodal officer, BBMP. The municipal corporation has identified “slums as critical as the risk of spreading the virus in these areas was very high.”

“The women healthcare volunteers are from the community. They know their areas and people well. They are doing a good job in bringing people for testing and vaccination,” adds Ichini. During the initial days of the vaccination drive, which started in the country on January 16 this year, vaccine hesitancy was huge in slum areas.

“Without our healthcare volunteers, vaccination would have been very difficult. They are the ones who motivated people to get vaccinated. Some of the volunteers set an example by taking the vaccine first and showed their community people that it is safe,” Sumitra BM, a coordinator from CFAR.

The target population of BBMP in 760 slums is 13,36,812. Already 83 per cent of the targeted population in slums has received the first dose.

According to BBMP’s data, released on November 9, 2021, out of 91.70 lakh eligible population for vaccination in Bengaluru, 87 per cent have got their first dose and 58 per cent their second dose.

Since the pandemic started, 29.9 lakh people in Karnataka have been infected by the virus. A total of 38,122 people have succumbed to the deadly disease. The latest data shows Bengaluru Urban district topped the list of positive cases, with a total of 12,52,831, followed by Mysuru with 1,79,297.

In India’s IT hub Bengaluru, the focus has always been on the city’s upwardly mobile population and their lifestyle. “The coronavirus pandemic has been a body blow to Bengaluru’s poor and marginalised population, mostly residing in slums overshadowed by high-rise buildings. At this critical juncture, it is the women from slums who are doing exemplary work in Covid-19 health response work. These slum women are now the breadwinners too,” observed activist Nagasimha Rao.

However, the struggles of the women are too many to make sense of what they go through on a daily basis. Along with poverty, caste and religious discrimination, the women from the slums are further marginalised because of their gender.

Twenty-three-year-old Shaziya, who would give only her first name, is from Ahmednagar slum. After her husband’s death, her in-laws abandoned her. She took up the work of a healthcare volunteer three months ago. “The work has given me financial independence. I look after my one-year-old daughter, my mother (who is partially blind) and my grandmother by working as a healthcare volunteer,” said a frail-looking Shaziya.

Women like Shaziya in slums are overworked as they do all household chores apart from earning money for their families. Moreover, most of the slum-dwellers struggle for three meals a day. Many families, along with their children, skip meals, as they can’t afford to eat, especially in the midst of soaring food prices. “Hunger is so common here. Nobody thinks it is an issue as we all have accepted it as our fate,” said Ruksar Banu (30), who runs a mini tailoring shop from her hut in Ramachandrapuram slum.

Abdul Majid, 50, Ruksar’s neighbour, who lost work in 2020, added that it had been ages since he had a proper meal. Both Ruksar and Abdul had taken the first dose of the vaccine. “We might be able to conquer coronavirus but not hunger,” lamented Ruksar.

A BBMP medical official, who did not want to be identified, said that the women volunteers should be provided with health insurance that would cover them for any eventuality. As they are from low-income earners, several women volunteers said that they had access to Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana, the National Health Protection Scheme, fund up to Rs 5 lakh.

While most of the healthcare volunteers are women, there are a few men too. Vijay K, 20, who is pursuing his bachelor degree in commerce, said he took up the job to finance his education. After attending classes in the morning, his work starts in the afternoon. “Earlier, I was working as a waiter in a restaurant. My father works as a ward boy in a hospital and it is difficult for him to sponsor my education,” added Vijay, a resident of Arundathi Nagar slum.

It is estimated that Bengaluru spread across 709 square kilometres is home to 12,764,935 people in 2021. As per the last census done in 2011, Bengaluru had 9,621,551 population.

In Bengaluru, nearly a quarter of the 12.76 million people live in slums. Unfortunately, different government agencies cite different slum figures in the city. Shankar Poojary M, deputy director of the Karnataka Slum Development Board, told The Federal that there were 409 notified slums in Bengaluru. However, there are 597 slum areas in the city as per the board’s website. The BBMP is conducting vaccination drives in 760 city slums. A study conducted by the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore along with foreign organisations found 2,000 slums in Bengaluru in 2018.

It is women from these invisibilised corners who now have the additional responsibility to ensure a monthly income to run their households, apart from looking after their families, even if that means putting their own health at risk.

After they were vaccinated, the women feel less vulnerable to the virus but the fear of a secure future still worries them.

When asked what they plan to do once the BBMP’s COVID-19 health response work ends, the women volunteers were clueless. “I definitely have to find a new job,” said Fouziya Banu, 34, from Devegowda slum.