- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

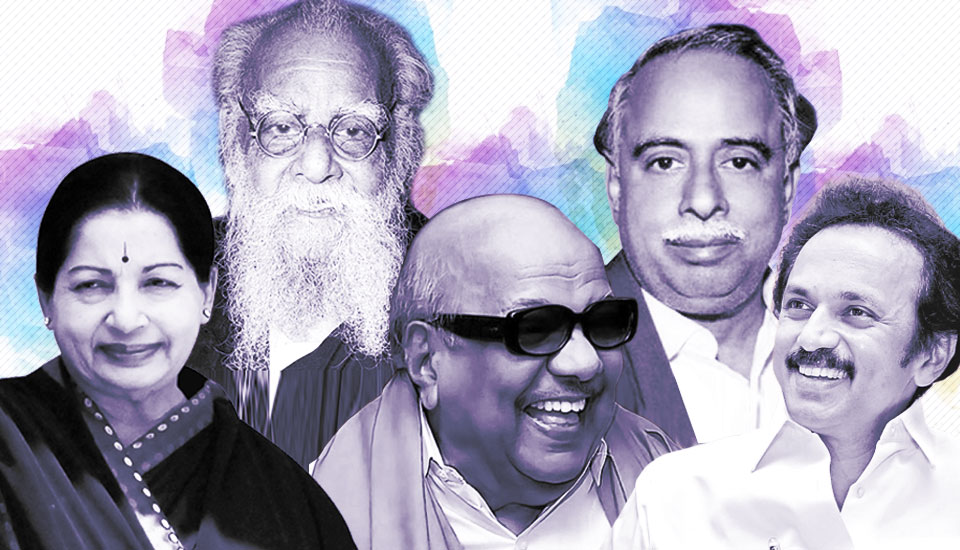

The true 'religion' of Dravidian politics

On a searing summer afternoon in April, DMK president MK Stalin passionately defended his party’s stand on god and religion. “The DMK is not anti-Hindu or against any religion, caste and god,” a visibly upset Stalin told a motley crowd in Tirunelveli, where he was addressing an election rally. The reason behind Stalin’s anger was the BJP’s...

On a searing summer afternoon in April, DMK president MK Stalin passionately defended his party’s stand on god and religion. “The DMK is not anti-Hindu or against any religion, caste and god,” a visibly upset Stalin told a motley crowd in Tirunelveli, where he was addressing an election rally. The reason behind Stalin’s anger was the BJP’s “deliberate attempt” to project the party as anti-god and anti-Hindu.

While commentators and critics have long argued the Dravidian parties’ stand on god, the Dravidian movement is by and large perceived as anti-god and anti-religion because of its rationalism. But, that is not always the case. On the contrary, Dravidian politics possibly unlocked the mystery of religion and embraced god wholeheartedly, if one were to go by the discourses of either CN Annadurai, the founder of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), or his successors. There will, of course, be counter-arguments to this narrative. However, the Dravidian political discourse has given enough indications that they were for a ‘just’ religion.

DMK veteran M Karunanidhi’s famous dialogue in the 1952 film ‘Parasakthi’ underpins this attitude. “I said no to a temple not because a temple is not wanted, but because it should not become the abode of evil-doers.”

When Annadurai reclaimed the slogan ‘Ondre kulam; oruvane thevan’ (One humanity; one god) from Thirumoolar, the sage-poet who authored Shaivite Bhakti literature “Thirumanthiram” in the 8th century, it was the tipping point for Dravidian politics in the then Madras Presidency. By reiterating the verses of a renowned saint-poet, the already “cosmopolitan” outlook of Dravidian politics became even more accepting and inclusive.

“It is in the smile of the poor, we see God” is another oft-repeated rhetoric of Annadurai. These words resonate deeply with people across the religious spectrum. The non-Brahmin movement’s engagement with the British created enough discourse in Tamil society about the use of ‘scriptures’ and ‘god’ to subjugate the ‘shudras’. For instance, the Dravidian political movement used the Ramayana to reconstruct a political identity in opposition to North Indian cultural hegemony. Ravana is portrayed as the symbol of the ‘oppressed’ Dravidians. Annadurai used the prevailing context to reclaim religion” and captured public imagination.

“It is in the smile of the poor, we see God” is another oft-repeated rhetoric of Annadurai. These words resonate deeply with people across the religious spectrum. The non-Brahmin movement’s engagement with the British created enough discourse in Tamil society about the use of ‘scriptures’ and ‘god’ to subjugate the ‘shudras’. For instance, the Dravidian political movement used the Ramayana to reconstruct a political identity in opposition to North Indian cultural hegemony. Ravana is portrayed as the symbol of the ‘oppressed’ Dravidians. Annadurai used the prevailing context to reclaim religion” and captured public imagination.

However, Dr N Ramasubramanian, a supporter of right-wing politics in Chennai, has a different take on this argument. “Annadurai endorsed saint Thirumoolar but his successor M Karunanidhi was stridently anti-Hindu. It is the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK)’s J Jayalalithaa who openly declared her faith in religion and brought a behavioural change in Dravidian politics,” he says. As a devout Hindu, he adds that he is unable to support the DMK, though some of its policies are very good and people-friendly.

Arjun Sampath, leader, Hindu Makkal Katchi, thinks that the DMK ‘assimilated’ god from the beginning. “In fact, the idea of seeing god in the smiles of the poor is borrowed from the Shaivite saint Manickavasagar. The DMK embraced god from the beginning. The DMK’s acceptance of PTR Palanivelrajan, a firm believer of god, as Speaker of the Legislative Assembly during its 1996-2001 rule, is a great example.” Sampath commends Annadurai’s oratorical ability in persuading ‘believers’ to be part of the Dravidian political movement.

Interestingly, Periyar EV Ramasamy (commonly known as Periyar), the rationalist founder of Dravidar Kazhagam (DK), too expressed his gratitude to god in the editorial of the first edition of ‘Kudiyarasu’ (Republic) magazine in 1925. “The rituals and caste are intricately tied to the tree of religion and god. I am trying to segregate caste from the tree of religion. When I am unable to do so, I am forced to oppose them altogether. Despite the opposition, if religion has some substance to withstand, it would continue to flourish,” is what Periyar had to say about his opposition to religion and god. He used to say to believers (in god) that his communication strategy of opposing god is to attract enough attention to the fact that inequality is perpetuated by the status quoists in the name of caste, religion and god.

Interestingly, Periyar EV Ramasamy (commonly known as Periyar), the rationalist founder of Dravidar Kazhagam (DK), too expressed his gratitude to god in the editorial of the first edition of ‘Kudiyarasu’ (Republic) magazine in 1925. “The rituals and caste are intricately tied to the tree of religion and god. I am trying to segregate caste from the tree of religion. When I am unable to do so, I am forced to oppose them altogether. Despite the opposition, if religion has some substance to withstand, it would continue to flourish,” is what Periyar had to say about his opposition to religion and god. He used to say to believers (in god) that his communication strategy of opposing god is to attract enough attention to the fact that inequality is perpetuated by the status quoists in the name of caste, religion and god.

Karunanidhi, in 2007, had said, “It is insignificant if I accept god or not; but it is highly significant that I should behave in a way that is acceptable to god.” Despite occasional ‘provocative’ statements related to devotion (bhakti), Karunanidhi made reverential remarks on god on several instances. “Kalaignar (Karunanidhi) followed Annadurai and spoke of how he sees god in the smiles of the poor on many occasions,” says Bala Janathipathi, a spiritual leader belonging to Ayya Vaikundar mutt, a reformist Hindu order in Nagercoil, Tamil Nadu. Janathipathi adds, “Dravidian politics did not oppose god as such; they condemned the atrocities perpetrated in the name of god.”

“Society requires religion as part of its daily life. We cannot leave god and live in peace. The Dravidian socio-political movement has clearly understood this,” says Swami Shri Hari Prasad of the Sri Vishnu Mohan Foundation. He adds that there have been occasional attacks on the Hindu culture by certain leaders of Dravidian politics but Jayalalithaa was never shy to flaunt her religious beliefs. In fact, the tradition of having heads of religious mutts endorse political views of Dravidian political parties existed since the 1940s, adds Swami Shri Hari Prasad.

Janathipathi is one of those who endorsed the Dravidian style of approaching religion and god. “People have faith. When people were oppressed in the name of god and caste in Kanyakumari district, we understood why rationalism was used as a tool to create awakening in the minds of the public.” He says the reformist teachings of Ayya Vaikundar (1809-1851), who prioritised love and equality as the messages of Hinduism, among other things, influenced the Dravidian political philosophy. The perpetuation of inequality in the name of god and religion ‘justified’ the discourses of Dravidian politics for some spiritual leaders, including Sri Deivasigamani Arunachala Desikar, who was popularly known as Thavathiru Kundrakudi Adigalar (1925-1995), and Madurai Aadheenam.

Well-known social scientist and Dravidian political history scholar MSS Pandian explains the relationship between Dravidian politics and religion in an article that appeared in Economic and Political Weekly dated August 4, 2012. Pandian quoted from one of the early interviews of Annadurai after he became the chief minister of Tamil Nadu in 1967. “I said true faith in god is to have faith in fellow human beings… Of course I am a rationalist who wants to end unreason and blind faith in the people. But genuine belief and true faith in god should be there amongst the people so that it helps them to become more and more aware and conscious of their duties and responsibilities to their fellow human beings.”

In the article, Pandian appreciates the ability of the Dravidian political movement to incorporate Muslims under the broad Tamil identity. He also appreciates the movement’s ability to create a Hindu religiosity that is self-critical and tolerant through consistent discourse on what religious faith ought to be.

However, author Badri Seshadri in Chennai has a slightly different understanding of the relationship between Dravidian politics and religion. “Dravidian political leadership has always been unclear about what to do with religion and god. While the Dravidar Kazhagam and its offshoots make anti-Hindu statements, the DMK and the AIADMK maintain a strategic silence on the issues related to god and religion.” He believes that non-interference in the religious affairs of individuals has become a strategy for the Dravidian political forces.

For the political discourse to move forward in Tamil society, it is essential to understand the context in which Dravidian parties ‘appropriated’ or ‘assimilated’ religion and god.

(Peer Mohamed is founder and CEO of ippodhu.com.)