- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The tale of a dying beach in Kerala

By the time the world comes back to normalcy after the COVID-19 shock, Shanghumukham beach in Kerala's Thiruvananthapuram would become a memory.

For many, Shanghumukham beach in Kerala’s capital Thiruvananthapuram is all about idyllic moments made memorable. But for Joy Freddy and his wife, Joyce, it is more than that. For the past 10 years, the couple has been making a living by selling roasted peanuts in one corner of the beach. Every evening, they would push the cart to their favourite spot and sell the nuts to a host of people,...

For many, Shanghumukham beach in Kerala’s capital Thiruvananthapuram is all about idyllic moments made memorable. But for Joy Freddy and his wife, Joyce, it is more than that. For the past 10 years, the couple has been making a living by selling roasted peanuts in one corner of the beach. Every evening, they would push the cart to their favourite spot and sell the nuts to a host of people, from children and young couples to the elderly. But all that stopped with the COVID-19 lockdown.

But Joy recalls that the downslide had begun much before.

“The sea is coming forward every year. Half of the beach is gone. The regular visitors have almost stopped. I don’t know how long it would take the sea to swallow the entire coast,” he says.

Shanghumukham beach used to be one of the favourite evening destinations of Thiruvananthapuram residents. Even on weekdays, hundreds of people frequented the beach to enjoy the serene beauty of the sunset.

The giant sculptures of a mermaid, the Children’s park, eating kiosks and the Indian Coffee House (which was closed a few years ago) added to the attractions that made a relaxing evening.

Over the years, the beach has undergone coastal erosion, a phenomenon by which land is lost to the sea, normally due to the action of waves and tides, but rise in sea levels over the years is said to be the main cause.

According to a study by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Kerala, which has a 580 km-long coastline, has seen 45 per cent coastal erosion over the years.

It is among the few states to have faced over 40 per cent coastal erosion, West Bengal (63 per cent) and Pondicherry (57 per cent), being the other two.

The report also states that while “the entire west coast of India is mainly stable, with isolated pockets of eroding coast”, Kerala is an exception to this. The costal locations of the state have been marking unsteady shoreline changes and erosion since a few years due to multiple factors such as climate change as well as human intervention.

Vizhinjam port muddle

Although the erosion of Shanghumukham and other beaches in Thiruvananthapuram started in 1980s, the process has accelerated because of the construction of Vizhinjam International sea port, says AJ Vijayan, a native of Thiruvananthapuram and convener of People’s Vigilance Forum, a civil society group which had raised protests against the project.

The protests died down after the Kerala government signed an MoU with Adani Group in 2015 to develop the port.

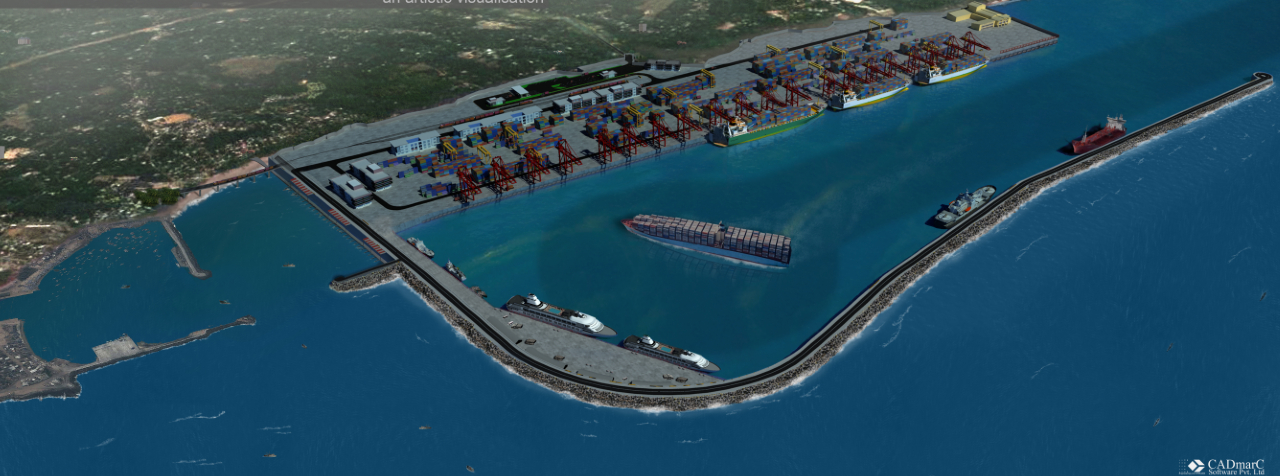

The multipurpose port project is envisaged to have total container berth length of 2,000 metre which would be developed in three phases (800m in Phase-1, additional 400m in Phase-2 and another 800m in Phase-3), apart from 600 metre cruise berth, 850 metre fish landing centres and a 220 metre Coast Guard berth.

The port is designed to primarily cater to the container trans-shipment business, with provision for a cruise terminal and general/multipurpose cargo area.

The first phase of the construction of the ₹7,500 crore-worth project was expected to be completed in October 2019. However, the project which was set rolling by the former Congress-led UDF government is a heavy liability for the government according to the report of the Controller and Auditor General (CAG).

The CAG report of 2017 had found that at the end of the concession period of 40 years, the project would cause a substantial loss of ₹5,608 cr. The CAG had also found that the total project cost compared to similar ports in other states was highly unreasonable.

The standard concession period is 30 years but it was enhanced to 40 years in this case. There were several other irregularities in the entire process and structure of the project. Since there were major changes in the project parameters, the CAG said the tender process should have been cancelled and fresh global tenders invited.

‘Effect on the beach’

Shanghumukham lies to the north of the port where large scale erosion happens. To its south, there is large scale accretion (accumulation or deposit of sand on coasts).

While Vijayan says erosion on and accretion is seasonal and happens regularly along coasts, the large scale erosion of sand from the northern coasts of the port and accretion in southern parts, he says, started with the construction of breakwaters in the sea.

It has been recorded that a significant amount of erosion and accretion happens along the coast of Vizhinjam port every year. The monthly analysis of shoreline changes along the 40 km coast by the National Institute for Ocean Technology in 2018-19 shows that in October 2018, Shanghumukham beach was found to have eroded at most of the stretches except at Panathura where there was high accretion. In November and December 2018, sediment deposition took place almost throughout the entire stretch.

However, in January 2019, the beach was found to have minor erosion and accretion at almost all locations, except at Kochuveli, where high accretion was noted. In the next two months, there was a considerable amount of erosion while in May 2019, most of the beaches in the northern side were found to have high erosion whereas most of the beaches at the southern side had accretion.

This constant erosion over the last few years has been worrying authorities and officials, besides local residents, for whom the sea is getting closer to their homes.

Santhosh, a native of Shamgumukham beach, has fond memories of spending the entire day and night on the beach. “I used to sleep on the beach with friends. All my memories of growing up are attached with the beach,” says Santhosh, who works at Thiruvananthapuram International Airport and hails from a fisher family.

The CPI(M) activist used to be an active participant in the protests against the port.

“The fishermen community live in poverty. It is very hard to maintain the momentum of the struggle among a people who have no means of livelihood,” he says.

Many who were against the port recollect that the fishermen were offered rehabilitation packages and people were told that the port was a landmark achievement in the development of the coastal belt and the state itself, and going against it would be “a sin”.

Sea takes all away

Besides being broken at many points, a road parallel to the beach that leads to the domestic airport is on the verge of collapse. The road continues to remain in disrepair since being struck by the 2017 cyclone Ockhi, which had caused widespread devastation and damage to houses and other buildings.

The 15-kilometre walkway from Veli to Shanghumukham through the beach too is almost non-existent. The broken sea wall and the devastated beach epitomise wrong preferences and false notions of development. Now everyone seems to realise the same.

“We had a handful of projects, but all were stalled as there is heavy coastal erosion at Shanghumukham,” says an official with the department of tourism.

Many like him from various other departments admit that the loss for the tourism industry is irreversible.

The beach is very much a part of the cultural life of the people. Hindus believe that it was at the beach that Lord Vishnu took incarnation as Anantha Padmanabhan, the deity at Thiruvananthapuram’s Padmanabhaswamy temple. Thousands of Hindus take a dip in Shanghumukham beach, considering it holy, and perform offerings.

Despite being a place of annual worship for the Hindus, Shanghumukham has been a place of gathering for all and has hosted innumerable processions, public gatherings, of political parties and civil society groups, besides beach festivals and art performances, reflecting the secular ethos of the place.

Santhosh says rough waves at nights make the beach alien to even those who were born and brought up here. “This is not the place it used to be. The sea looks scary now,” says Santhosh.

Joy, the peanut seller, feels that by the time the world comes back to normalcy after the COVID-19 shock, Shanghumukham beach would become a memory.