- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The story behind Kerala’s first printing press and the cultural evolution it sparked

The history of the first Achukoodam (Malayalam for printing press) in Kerala’s Kottayam goes back 200 years. Until then copies of books were laboriously inscribed by hand for which journalists charged hefty amounts. Not only did the printing press prove to be a boon for readers, it also marked a watershed moment in the socio-cultural evolution of the state. The CMS Press in Kottayam...

The history of the first Achukoodam (Malayalam for printing press) in Kerala’s Kottayam goes back 200 years. Until then copies of books were laboriously inscribed by hand for which journalists charged hefty amounts. Not only did the printing press prove to be a boon for readers, it also marked a watershed moment in the socio-cultural evolution of the state.

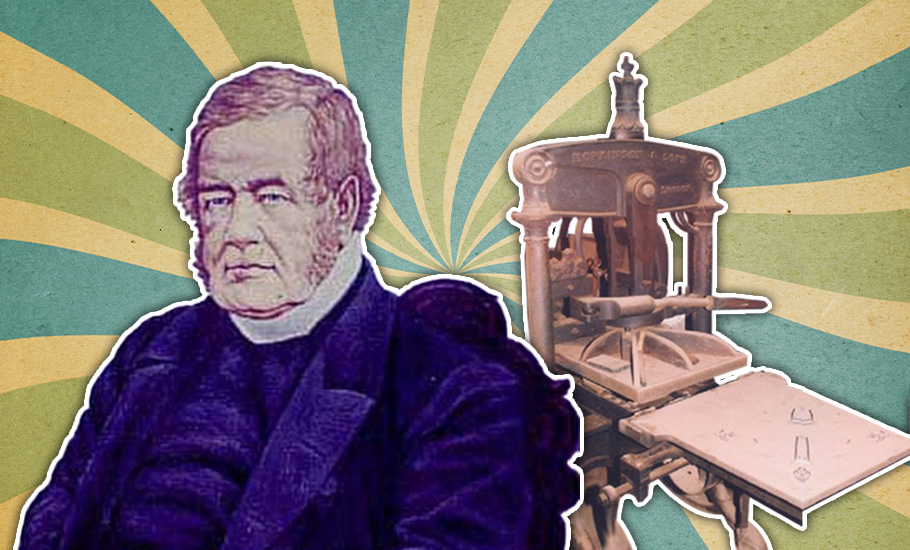

The CMS Press in Kottayam was established on October 18, 1821, in a bid to put an end to inscribing books, an exercise that was both time consuming and expensive.

It was Colonel Monroe who presented the idea of starting a printing press in Kottayam to print copies of the Bible. Munroe reasoned in favour of setting the printing press in Kottayam thus: “The translation of the scriptures will be completed in the course of another month; and two or three Catanars [priests] may be sent with the manuscripts to Calcutta. But would it not be a better plan to establish a press, and print the scriptures in the College at Cotym [Kottayam]. There is ample room in the College for a printing and book binding establishment, and the formation of such an establishment at that institution would, in my judgement, be very useful.”

This was a time when the translation of the Bible and many other literary works was going on under Benjamin Bailey, a British Church Mission Society missionary in Kerala. So, the missionaries in Kottayam raised a demand before the Madras Corresponding Committee to establish a printing press.

According to the Missionary Register of December 1821, they argued that “a Syrian press is perhaps even more requisite from the great expenses of Syriac works in England, and the impossibility of procuring them in sufficient numbers from home. But, of all the presses needed here, the Malayalam press is undoubtedly of the first importance.”

Since the Madras Corresponding Committee was convinced with the arguments given by Colonel Monroe and the missionaries, they soon wrote to the parent committee in England asking for a printing press and typing equipment for printing in English and Syriac. They also suggested making available the metal for casting types in Malayalam, Tamil and Sanskrit indigenously. The printing press and English types reached Kottayam on October 18, 1821, through the Bombay-Alappuzha route, ushering in a revolution of sorts for the socio-political and economic milieu of Kerala.

A Syrian press is perhaps even more requisite from the great expenses of Syriac works in England, and the impossibility of procuring them in sufficient numbers from home. But, of all the presses needed here, the Malayalam press is undoubtedly of the first importance.

(Missionary Register 1821 December 518)

Hundreds of books, including religious texts, dictionaries, grammar books, textbooks in Sanskrit, English and Syrian languages were printed at this press.

On the 200th anniversary of the establishment of the first printing press, the Benjamin Bailey Foundation and the Sahithya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society published a huge volume of critical study which comprises details of the diverse modernist processes created by Malayalam printing since 1821. According to this study, which comprises an oeuvre of 39 theses published in two parts in Two Hundred Years of Malayalam Printing, the printed texts of over 200 years capture the diversity of the work covered from the period of missionaries to the current digital age.

The study comprises academic articles tracing the development of language, printing, technology and language peculiarities.

The study covers the transition seen in printing technology and medium, the change in the styles from printing classical languages to printing modern languages. It also touches upon the paths through which discourses on nation-states have travelled in texts, the diverse experiences which were reflected through printing in different modes (pamphlets, newspapers, weekly magazines and books), and how content comprising news and even advertisements shaped the transition.

According to the study, the 200 years of printing was diverse in form, content and ideology. It could be categorised under four epochs. The first phase was from 1820 to 1880, which marked the transition from missionary publishing to regional publishing. It was the era of secular books and the modern literary forms. The period witnessed the beginning of journalism, the launch of the literacy mission and the independent institutions of state.

The second phase, which began by the 1880s, emphasised on the expansion of literacy and reading, the publishing of books and newspapers. It also witnessed an increase in publishers and editors, the intensification of the national and social reformation movements. This period also witnessed the emergence of luminaries such as Kandathil Varghese Mappillai, Chengalathu Kunjirama Menon, Swadeshabhimani Ramakrishna Pillai, Kesari Balakrishna Pillai, ST Reddiar, besides the Sahithya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society (SPCS) and newspapers such as Kerala Mithram, Kerala Pathrika, Nasrani Deepika, Malayala Manorama, Mathrubhumi, Deshabhimani and Kerala Kaumudi in the media renaissance of Kerala.

This was also the time of the formation of political parties such as the Indian National Congress, the Communist Party and the start of the library movement and the literacy mission.

The period from 1880-1950 is important from the standpoint of modernism in Kerala. And the role of printing in shaping that is crucial.

The third phase, which began by the 1950s, is characterised by growth in the printing industry and its transition to public culture. The phase was marked by the expansion of newspapers and weeklies, the resurgence of people’s literature and the unprecedented growth of publishing houses, libraries and reading rooms. This period also recorded a manifold growth in translated, independent, literary and scientific books.

The fourth phase, which started in the 1990s, witnessed the emergence of a new printing culture owing to the influence of globalisation and electronic media. This phase saw the evolution of language and lipi (script). This is the period which recorded the meteoric growth of print media. The study says the 1990s witnessed the decadence of weeklies in terms of circulation and a meteoric expansion of Malayalam newspapers with a 400 per cent growth. The newspaper circulation, which was 12 lakh per day in 1992, recorded a growth of 48 lakh copies within a span of 15 years to rise to 50 lakh copies sold each day. It was in this phase that printing transformed to digital mode from paper.

In her thesis, ‘Print Modernity and the Making of Literary Visualities in Kerala’, Kavitha Balakrishnan describes how pictures were used in periodicals. “The Malayali public domain created by the periodical press depended more on diffusion of a world culture. A clear and detailed graphic world was formed though that was used far more sparingly than the worded space. Pictures were employed more to suggest a grandeur that could be ascribed to the very act of reading,” Balakrishnan wrote.

In his thesis titled, ‘Toward the Traces of Transition: Language and Modernity in Kerala print culture,’ Krishnan Unni P writes, “The primary set up of Malayalam printing, needless to say, has evolved from the Sacred Congregation propaganda in Rome in the second half of the 18th century. As the 18th century is well known for the rise of European enlightenment, the methodology to transfer different knowledge systems from European countries to others in the East assumed a layer of oriental enlightenment. The Malayalam letters that were already in circulation at the time of the 18th century and those appeared in print in the botanical treatise, Hortus Malabaricus (Garden of Malabar), can be seen as the early transformative traces that gave rise to the new epistemological rise of the script.”

According to him, the 19th century Kerala was not accommodative to the revolutionary changes in printing. “The overt patriarchy that was in control of the families and the matrilineal system prevalent in Hindu families were not very supportive of secular education. Though at some centres, secular beliefs were visible, the missionary and evangelical education systems and printing process were viewed with internal doubts and suspicions even in the Malabar by some Muslims. The real plight of the elite women from the matrilineal society in Kerala, despite the printing evolution, was to remain in the dark corners of illiteracy,” he added.

Unni observes that the caste system in Kerala also played a crucial role in segregating and dividing the ways of understanding scripts and letters. For instance, while marginalised people in Kerala received education and were able to read and write, traditional caste people such as toddy tappers, weavers, fishermen, land tillers, manual scavengers and several others never benefited from the revolution that printing ushered in.

In the mid-19th century, only about 20 per cent people in Kerala could read and write. The transition of society into the new culture, therefore, was not that smooth as the print culture didn’t have an impact upon a wide range of masses, he writes.

Noted scholar KM Govi says, “By the end of the 19th century, Kerala Vilasam (Thiruvananthapuram), St Thomas printing press (Kochi), CMS Press (Kottayam) and the Basel Mission Press (in Mangalore) were the main institutions in the publishing field. The first printing houses discharged the fundamental functions in the book trade, that is, printing, publishing and sale. Kerala continues that initial experience till date. All of the aforementioned institutions, apart from the Basel Mission, were regional outfits in terms of their scope and functioning — they printed and published articles only at places where the works originated.

In an academic article, ‘Printing, Renaissance, Modernism: Kerala Studies,’ professor Shaji Jacob says, “The influence exerted by printing in the field of politics helped shape the modern nation states. Empires emerged instead of city states after the laws and tenets written in Papyrus were sent to faraway places. Feudalism emerged once there was a scarcity of Papyrus. As soon as the printing press and less expensive papers were invented, nationalism and new political and economic empires also developed.”

“The establishment of the first printing press was the beginning of the modernisation of Kerala. While giving equal importance to printing and publication of religious texts, Benjamin Bailey, CMS Press and the book depot published not only Bible but also dictionaries, grammar books, textbooks and scientific books apart from tracts and literary works. They were printed in Malayalam, English, Sanskrit and Syrian languages,” says professor Babu Cherian.

Noted scholar Scaria Zacharia in his thesis, ‘The Prose Used by Missionaries’, says the Malayalam ‘missionary literature’ discharged a historic duty by exploring the nitty-gritty of the Malayalam language for presenting foreign ideas. It was due to the ‘missionary literature’ that prose writing became mainstream. It is the missionaries who used Malayalam language to shape the society even though the residents of the state earlier used it only to speak with each other.

Prof Zacharia believes that the emphasis laid out by missionaries on Malayalam prose could a western influence.

Eminent writer Anand, in an article in Book, Booksellers, Libraries, Dictionaries and Wars, says printing technology brought a revolution in production of books.