- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

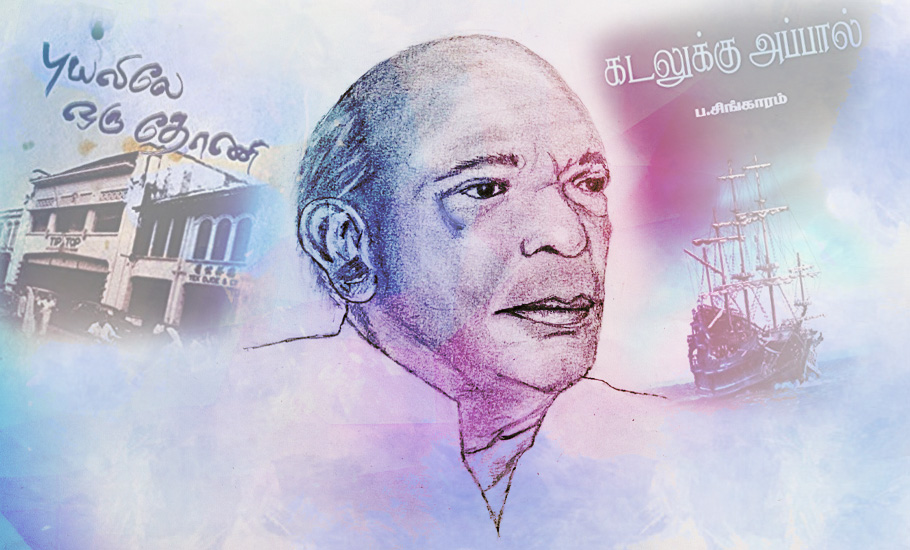

The sea that lay between Pa Singaram and literary world's indifference

Set against the backdrop of the Second World War, Pa Singaram’s novels are some of the earliest known literature on Tamil migrants and seafarers.

The world of Tamil literature is not limited to the boundaries of Tamil Nadu alone. It stretches across nations such as Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Singapore. Often, the literature created outside of Tamil Nadu or India is termed as ‘migrant literature’. But there is a difference. Both Malaysia and Singapore, which have a large Tamil population comprising people who went from...

The world of Tamil literature is not limited to the boundaries of Tamil Nadu alone. It stretches across nations such as Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Singapore.

Often, the literature created outside of Tamil Nadu or India is termed as ‘migrant literature’. But there is a difference.

Both Malaysia and Singapore, which have a large Tamil population comprising people who went from pre-Independent India as British slaves to work in rubber estates or to find a suitable work, have their own Tamil literature. The Tamils there write and publish their work and those works mostly do not travel outside those countries.

In contrast, Tamilians who migrated from Sri Lanka due to the civil war are mostly spread over in Western countries such as France, Canada, Norway, etc. Their works, however, were published and discussed in Tamil Nadu.

The literature of Sri Lankan Tamils largely talks about their motherland ripped apart by war and today, these are considered as ‘migrant literature’ in its fullest sense.

While the Tamil literature of Southeast Asian countries has a history of more than 120 years, that of Sri Lankan refugees and migrants is only 30–40 years old. Malaysian and Singaporean works talked about the lives of Tamils there in the ‘present’ sense, whereas those by Sri Lankan Tamils focussed mostly on their ‘past’.

But there was a vacuum in the literature about the early migration that happened from India to the Southeast Asian countries—until Pa Singaram came up with two novels Kadalukku Appaal (Beyond the Sea) and Puyaliley Oru Thoni (A boat amidst the storm) published in 1959 and 1972, respectively.

Set against the backdrop of the Second World War, these novels are also the first works in Tamil that spoke about war.

Revisiting these novels would be a fitting tribute to the author in his birth centenary, even though he did not want the world to even know about his death.

Struggling to publish

Pazhanivel Singaram was born at Singampunari in Sivagangai district on August 12, 1920. He was the third son of Ku Pazhanivel Nadar and Unnamalai Ammal couple. His grandfather Kumarasamy Nadar and father were into cloth trade.

He did his schooling at Singampunari primary school and St. Mary’s higher secondary school. Having a knack for business, particularly in financial transactions, Chettiars from Sivagangai were pioneers in banking. They also ran ‘Vattikadai’, money lending shops, not only in their region but also in Southeast Asian countries such as Burma (now Myanmar), Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam.

The owners of those shops used to take the people, mostly men from their region, to work in their shops abroad. These included ‘Samayalaal’ (a cook), ‘Pottiadi paiyyan’ (a person who cleans the shop and also goes to collect the interest from the borrowers), ‘Aduthaal’ (an assistant to manager) and ‘Meylaal’ (manager). They were not treated as employees but as family members.

In 1938, Singaram went to Medan, the capital and the largest city of North Sumatra, a province in Indonesia, as ‘Aduthaal’ at the age of 18. He was there for eight years. In 1940, he became a clerk in the maintenance department with Indonesian government. It was during this time that the Southeast Asian theatre of World War II had started.

During the war, he and his friends started a business of sending essentials from Indonesia to Penang in Malaysia.

At 25, he got married, but lost both his wife and child during delivery. That had a lasting impact on him. He maintained loneliness till his death in 1997. After his return to India in 1946, he worked in ‘Dina Thanthi’, a Tamil daily at its Madurai edition. He worked there for 40 years and retired in 1987.

In the early 1950s, he wrote Kadalukku Appaal, but it took nearly a decade to publish it. The work was rejected by many publishers due its new theme. It finally got recognition when it got a prize in a novel competition conducted by Kalaimagal magazine. Eventually, in 1959, it got published as a novel. That encouraged him to pen another novel Puyaliley Oru Thoni in 1960. Unfortunately, that too was rejected by many publishers until Kalaignan Pathippagam published it in 1972.

“It saw the light of the day due to the efforts of Malarmannan, a journalist. The fact that Singaram was also a journalist played its part in the publishing of the work. In those days, the books were published using ‘letterpress’ technology. The books were published page wise as 16 pages, 32 pages or 64 pages depending whether the publishing house is big or small. They cannot send it to the writer who lived in Madurai for proofreading, because it delayed the publishing process. So, the editing and proof was solely done by the publisher. They usually appoint a retired Tamil teacher to go through the proof. While doing so, much of the work was edited without the knowledge of the author. The edited parts were lost forever,” says writer and literary historian C Mohan, through whose writing, the Tamil literary world came to know about Singaram.

The edited parts, Mohan says, contain information about philanthropist Chidambaram Annamalai Chettiar’s feast where 96 different vegetarian items were served and guerilla war training was given in the forests of Indonesia.

War and Loss

Kadalukku Appaal talks about the life of Chellaiah, a former member of the Indian National Army (INA) founded by Netaji Subash Chandra Bose. Puyaliley Oru Thoni is an extension of the first novel and talks about the life of Pandian, another member of the INA.

Both the heroes migrated to Medan from Chinnamangalam, their hometown in Tamil Nadu, when they were young to work in the money lending institutions run by their relatives. Their lives change once they are attracted to INA. While the first novel has a parallel love story between Chellaiah and Maragatham, the second novel is mostly filled with philosophies and ideas that discuss the meaning of life, separation and Tamil culture.

These novels could also be the first-of-its-kind works that documented the money lending business run by Chettiars. Many might think that running a money lending shop is an easy and profitable business but it has its innate problems. When the boys go to collect the interest, the borrowers, who were mostly Malayans, Chinese and Japanese, can even beat them black and blue. The boys are not supposed to retaliate since it might affect their business.

For such boys, who were brave enough but cannot retaliate, the INA gave a space to become adventurous. In WWII, Japan was attacking the Southeast Asian countries which were under the British. It was during this time that Bose formed the INA with the help of Japan. In 1945, with the end of the war, the British regained the countries from Japan and Bose too had died in a plane crash. With his demise, the INA started breaking. The youths returned to their old selves and some to India.

“Singaram attempted a world class novel equal to War and Peace, particularly in Puyaliley Oru Thoni,” poet Shankarramasubramanian wrote in one of his articles. “At a time, when the novel form in Tamil mostly dealt with the ‘institution of family’, Singaram’s novels broke new ground.”

Published in 1876, Mayuram Vedhanayagam Pillai’s Prathapa Mudaliar Charithiram is considered the first novel in Tamil.

“In 1977, when writers Chitti and Sivapatha Sundaram brought out a book titled Tamil Novel Nootraandu: Varalaarum Valarchiyum (Centenary of Tamil Novel: History and Its Growth), the novels got missed out. Many didn’t know the existence of such works. The Tamil literary world overlooked Singaram’s novels. That discouraged him from attempting new works,” says Mohan.

A social scientist

Singaram was a social scientist in the disguise of a writer, says N Murugesa Pandian, a writer who met Singaram in the later stage of his life.

“Some novels get more attention during the lifetime of a writer. After his or her death, the work may be forgotten. Some novels gain attention after the death of a writer and stand forever. Singaram’s novels fall in the second category. He recorded his minute observations about globalisation induced consumerism and guerilla warfare in the 50s itself. He discusses Tamils consuming beef that has been recorded in Sangam age. Today, we are seeing disputes over meat eating. Without having a vision about the future and understanding politics, a writer cannot write such things. Though he has deep knowledge of ancient Tamil literature, he was also critical of them,” he says.

Singaram was heavily inspired by Ernest Hemingway and this was reflected in places where he writes about war and sea voyages, says Pandian.

Documentary filmmaker Kombai Anwar, who visited the places in Penang mentioned in both the novels, says that more research needs to be done about the participation of Tamils in INA and these novels can be a good start.

“The Tamil society is basically a seafaring society. We have a long trade relationship with Southeast Asian countries. The sea has been a link that connects different cultures and is not a barrier. The Tamil Muslims were at the forefront of carrying the businesses and the Chettiars came much later,” says Anwar, whose documentary Yaadhum was released in 2013 at Penang.

Only two years before its release did the Tamils in Penang come to know about INA’s connection with the region, he says.

“When I said that these two novels were based in Penang, the people were surprised,” said Anwar.

“The Tamil literary world has a tradition that initially it overlooks a work and later embraces it widely. That has come true in Singaram’s case,” says Vediyappan, publisher, Discovery Book Palace, which has recently brought out these novels as an annotated edition.