- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

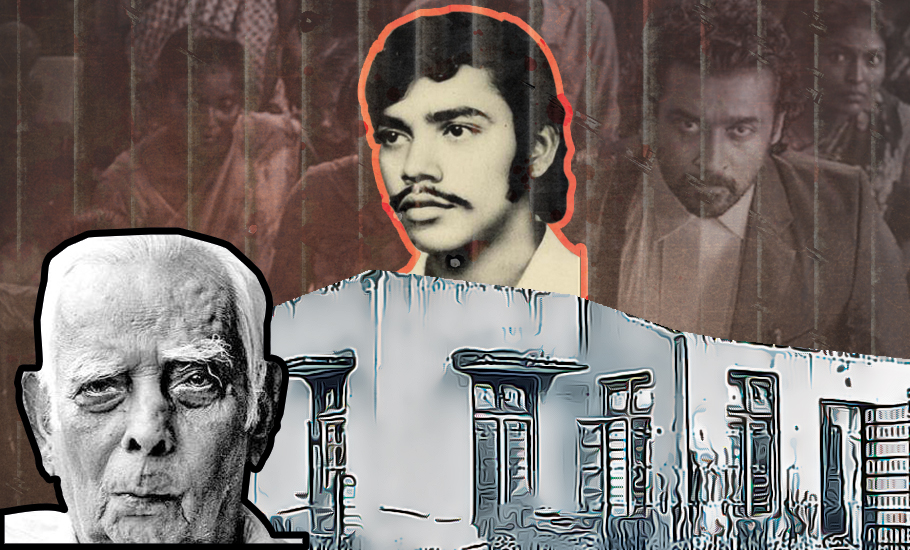

The Rajan case that Jai Bhim refers to in passing

In 1993, a heavily pregnant Parvathi, holding her young girl child by one hand, started a desperate search for her husband Rajakannu who went missing from police custody in Tamil Nadu. The search that spanned Tamil Nadu and the neighbouring state of Kerala found the Madras High Court in between. TJ Gnanavel’s movie Jai Bhim has now told us all how Parvathi’s (presented as Sengani and...

In 1993, a heavily pregnant Parvathi, holding her young girl child by one hand, started a desperate search for her husband Rajakannu who went missing from police custody in Tamil Nadu. The search that spanned Tamil Nadu and the neighbouring state of Kerala found the Madras High Court in between.

TJ Gnanavel’s movie Jai Bhim has now told us all how Parvathi’s (presented as Sengani and played by Lijomol Jose) search ended in finding not Rajakannu but his body dumped by the roadside to make a custodial killing pass off as a road accident. The film explores and explains how high court lawyer K Chandru (played by Suriya) could help Parvathi find her husband – now dead.

Parvathi may have never found even her husband’s body had it not been for the struggle waged by a father to find his missing son in 1976. To get to the truth of what happened to Rajakannu, Chandru asks the Madras High Court to allow him to question witnesses but witness examination wasn’t allowed under Habeas Corpus.

For the uninitiated, Habeas Corpus is a legal recourse that allows a person to report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, to bring the prisoner to court, to determine whether the detention is lawful. To tide over this legal tangle, Chandru quotes the Rajan case, a Habeas Corpus case where the Kerala High Court allowed witness examination. This proves to be the turning point in Parvathi’s case as questioning of witnesses allows the brutal truth about what happened to Rajakannu to reveal itself.

But what happened to Rajan

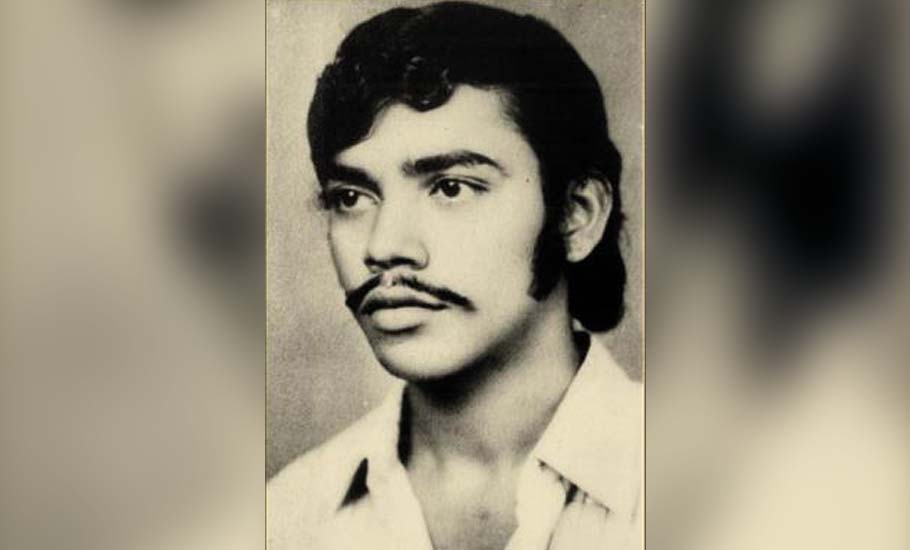

A happy go-getter, music lover and secretary of the Arts Club at Calicut Regional Engineering College, P Rajan was picked up the Kerala Police on March 1, 1976 from his hostel. A student named Joseph Chali was also picked up along with Rajan. The country was under a national Emergency that gave the police arbitrary powers to arrest people.

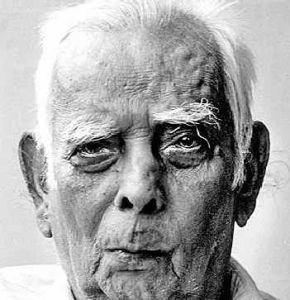

Following the arrests, professor KM Bahauddin, the then principal of the college sent a registered letter to Rajan’s father TV Eachara Warrier informing him that his son had been picked up by the police. And thus began Warrier’s search for his missing son.

After meeting some people, Warrier pieced together the information that his son had been picked up on the directions of Inspector General of Police of Crime Branch. On March 10, Warrier met then Kerala home minister K Karunakaran who promised to look into the matter. Nothing, however, happened. Refusing to give up, Warrier sent several letters to the Home Secretary, the Government of Kerala. In response, he did not even get an acknowledgment that his letters have been received.

Unrelenting, Warrier continued writing letters to eminent persons, including President of India, the Union Home Secretary, the Prime Minister and members of the Parliament from Kerala.

With no response from any quarters, Warrier filed a writ petition in the Kerala High Court.

Justice Subramanian Potty and Justice V Khalid in the Kerala High Court decided to look beyond the evidence on record in the Habeas Corpus petition submitted by Warrier and ordered witness examination to find the truth. Them home minister K Karunakaran, home secretary Narayanaswamy, IG VN Rajan, DIG Jayram Padikkal and superintendent of police K Lakshmana were summoned as respondents.

By this time, Emergency had been lifted and national elections announced. Warrier distributed pamphlets detailing his son’s case and how no one was giving him any answers on Rajan’s whereabouts.

The Lok Sabha was dissolved on January 18, 1977, and elections to both Parliament and the Assembly were scheduled for March. Congress leader K Karunakaran in his public meetings across Kerala said that Rajan was a suspect in a criminal case and was arrested in the case.

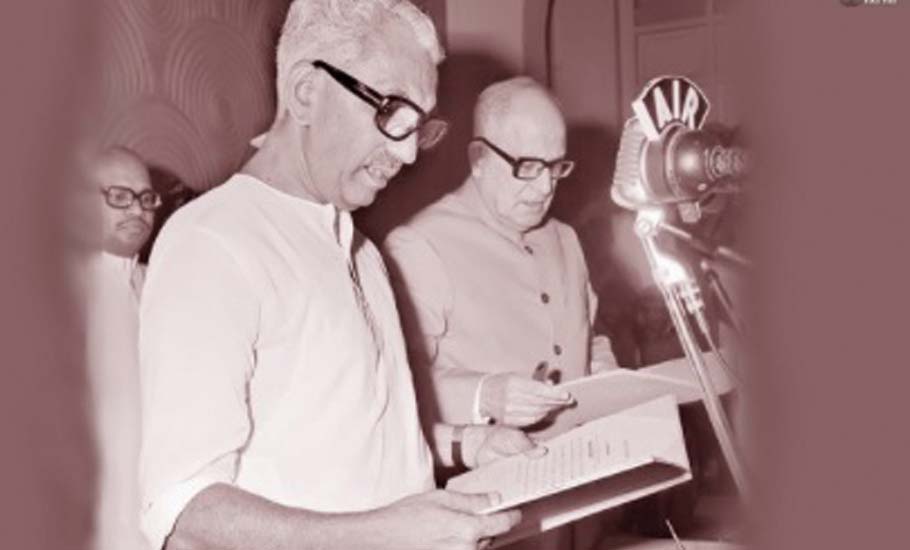

While the Congress paid a heavy price for imposing Emergency in other states, people in Kerala voted for the party. On March 25, 1977, K Karunakaran was sworn in as the chief minister of Kerala in the Congress-led United Front government formed with the support of the Communist Party of India and Revolutionary Socialist Party.

Immediately after taking over as chief minister, K Karunakaran made a statement in the assembly saying that Rajan was never taken into custody and his whereabouts are unknown.

Warrier’s Habeas Corpus

Ironically, it was on March 25, 1977, that Warrier submitted Habeas Corpus petition in the Kerala High Court.

The students who were present in the hostel at the time of the arrest, college principal professor Bahauddin, the sweepers, the warden, the mess boy, the security guard and all other relevant witnesses were examined.

The depositions unfolded the blooded story of the arrest and custodial torture of an innocent youth. Rajan and Joseph Chali were picked up at 6.30 am from their hostel on March 1, 1976 and were dragged into a van. Both were arrested for suspected connection with the Naxal movement. Witnesses confirmed seeing the duo being picked up. The loud cries were heard from the van. They were taken to a lodge first and then to the tourist bungalow in Kakkayam which was functioning as the police’s camp office during Emergency.

Another prosecution witness whose testimony proved crucial in the case was a man running a type writing institute. His name also was Rajan and he was picked two days before the arrest of P Rajan, the engineering student. Rajan who was there in custody in the Kakkayam police camp deposed that he had witnessed six policemen torturing the student so brutally that he fell unconscious. He identified sub inspector Pulikkodan Narayanan and the then superintend of police Lakshmana.

Piecing the testimonies together, the court was convinced that Rajan was indeed in police custody.

What happened to him after that? Was he still there in the custody? These were some of the questions the court demanded answers to from the police.

The division bench of the Kerala High Court discarded the offer put by the Advocate General that a commission would be established to investigate the case. “We are not impressed by this offer. That apart, that would not be an answer to this writ – We cannot abdicate our function to adjudicate on this application in the hope that Government may in due course set about finding about the truth of the case. We are constrained to decide this case on the evidence before us,” Justice Subramaniam Potty and Justice Khalid said.

The ground breaking judgment ordered that Rajan has to be produced before the court on April 21, 1977. “Whether he is still in police custody and if not how such custody came to an end, has to be found out. We do not feel that any such honest anxiety is reflected in the offer to appoint a Commission. We know that failure to comply with the direction to produce Sri Rajan may result in the respondents being held guilty of contempt.”

On April 19, the Karunakaran government submitted an affidavit in the High Court pleading the inability to produce Rajan. The government said that Rajan was not in custody and his whereabouts where not known. A Habeas Corpus petition is said neither punitive nor deterrent, only remedial. The failure to produce Rajan could have been interpreted as a contempt of court by the chief minister. Before that could happen, Karunakaran stepped down from the chief minister’s chair on April 25.

Investigations revealed that Joseph Chali was held under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act. Chali was subsequently released.

Unlike Parvathi who received some closure after seeing her husband’s body, Eachara Warrier and his wife Radha never saw their son, not even his body. Some digging in by journalists and activists later led to the assumption that Rajan was killed in custody in the Kakkayam Police camp and his body was burnt to wipe out evidence.

Unable to deal with the trauma, Rajan’s mother became mentally unstable and later died. “K Karunakaran was personally known to me. He could have told me that my son was no more when I pleaded with him for information about Rajan, Instead, he lied to me. If he cared to tell me the truth, Rajan’s mother would not have died with a derailed mind,” Eachara Warrier told this reporter during an interview in 2001. He passed away in 2006.

His book Memories of a Father written in Malayalam was widely read. He concludes the book saying, “I still have no answer to the question of whether or not I feel vengeance. But I leave a question to the world: why are you making my innocent child stand in the rain even after his death? I don’t close the door. Let the rain lash inside and drench me. Let at least my invisible son know that his father never shuts the door.”