- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The International Space Station: A home in the sky

Stationed 400 km above the earth's surface, the International Space Station (ISS) or the home in the sky circles the earth 16 times a day and has been doing so for the past twenty years.

Did you know the third brightest object in the sky — after the sun and moon — is human-made? It is a 455-ton football-field-sized, marvelously engineered spacecraft — the International Space Station (ISS). Stationed 400 km above the earth’s surface, the ISS circles the earth 16 times a day and has been for the past twenty years. Fifteen nations put their expertise together to...

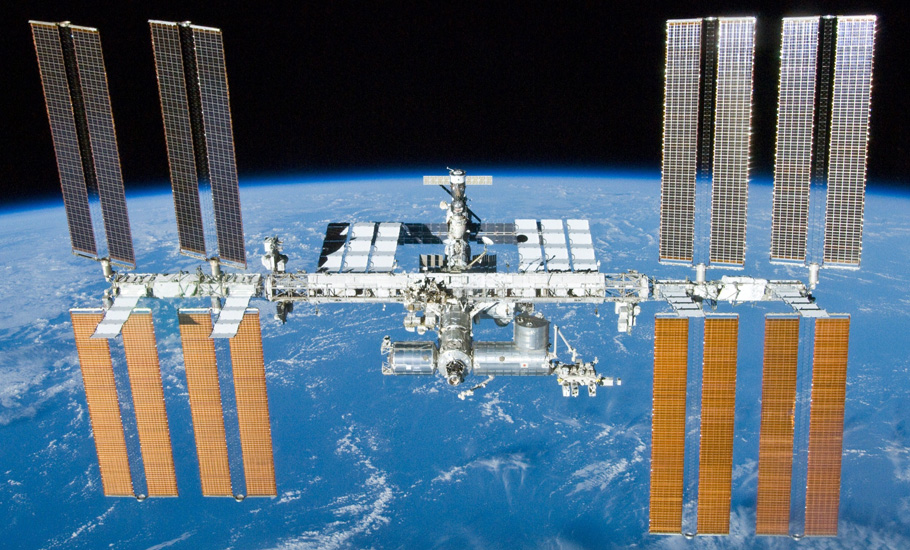

Did you know the third brightest object in the sky — after the sun and moon — is human-made? It is a 455-ton football-field-sized, marvelously engineered spacecraft — the International Space Station (ISS).

Stationed 400 km above the earth’s surface, the ISS circles the earth 16 times a day and has been for the past twenty years.

Fifteen nations put their expertise together to build the ISS. It has grown over the years from a few modules to what it is today. As many as 241 people and 19 tourists belonging to several nations have visited the ISS so far. At all times, at least five people reside on this orbiting habitat.

Just as all things come to an end, the ISS may not be permanent. In the coming decade, the ISS will be deorbited to make way for a more challenging venture — the moon habitat.

Whatever be ISS’s fate, a trip around its corridors is always in order, evoking awe and inspiration. Here’s a tour of the home in the sky.

The unconventional home

The ‘space home’ is a far cry from the homes we live in on earth. Life in space can be daunting and requires months of special training to adapt to it. There is no orientation in space; hence, there’s no concept of up, down, floor or ceiling, nor are there any dedicated rooms on the ISS. The space is cramped, with limited supplies with no scope for luxuries, like a bed or private washroom. Astronauts sleep in tiny cubicles, snuggling into form-fitted sleeping bags.

Yet, ISS is home to many, as each one of them who has been to it has always wanted to go back and live longer on the orbiting habitable laboratory.

From the outside, the ISS looks like an insect with wings. A long 200-ton stainless steel truss runs along the length of the spaceship, forming its spine. All the cabling, science equipment, power units, and solar panels are fit along the truss. The habitable spaces are the long tubular structures running perpendicular to the truss.

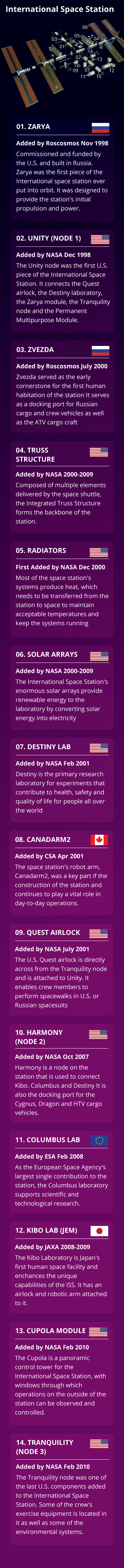

The habitat comprises 16 pressurised chambers built by the collaborative efforts of five space agencies of Russia, the USA, Japan, Europe, and Canada. The Russian module has five units (Pirs, Poisk, Zvezda, and Rassvet), the US nine (Zarya, BEAM, Leonardo, Harmony, Quest, Tranquility, Unity, Cupola, and Destiny ). JEM-ELM-PS and JEM-PM belong to Japan while Columbus to European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadarm to Canada. Working unitedly, the modules function to sustain the habitat and conduct crucial space experiments.

As we step into the ISS, it is apparent that every inch of the space station is utilised. Computers, wires, testing paraphernalia, monitors, and other machinery are all around. Everything is fastened to the walls, lest they begin to float under weightlessness.

Meandering through the corridors

The Soyuz spacecraft takes us to the ISS. After docking at the Pirs, Poisk, or Zvezda ports, you squirm your way into the station through a narrow port into the sector called Node 1 — a central point connecting six compartments.

To the left of the entry is Columbus, where experiments are underway to grow plants in space. A panel on the wall is fitted with equipment to collect blood samples to monitor the astronauts’ vitals periodically. They are then stored in a freezer chamber on another wall to be stacked and sent back to earth for evaluation.

On Columbus’s right is a port that takes us to Node 2, a docking port earlier for the space shuttles but now modified to receive cargo. Node 2 is also the place where the astronauts have their sleeping quarters — small cubicles with sleeping bags and computers.

Ahead are a row of labs belonging to the different space agencies. It’s a maze of wires and equipment covering the walls, indicating that several experiments are running. Guard rails are placed all along for the floating people to hold on and navigate through.

At the end of the corridor is a gym. A specially designed equipment with modifications and harnesses keeps the user stationed on the machine. The astronauts are trained to workout on these machines for 2-3 hours daily to not lose muscle mass due to the absence of gravity.

On another wall is a control unit dedicated to operating the Canadarm, the robotic arm fitted to the Truss. The astronauts perform several repairs by using this, maintain the habitat’s external parts, and even haul docking modules to place from the ISS confines.

The corridor ends with turns on both ends. One end leads to the dining quarter — where the inmates assemble to eat prepacked, dehydrated food. Even the water pouch is specially designed. The astronauts must use it in a particular way so as not to let water bubbles fly away.

At the opposite end is the Airlock, the chamber where spacewalkers gear up to venture out for extravehicular activity (EVA), like repairs. The EVA suits are stored here. The Airlock leads to a small depressurising unit, which separates the inside from the outside.

At the entrance of Airlock is a downward port that leads to a big storage dock for the supplies. It is also the place where trash is stored to be stowed away by the cargo ship.

To the central shaft’s right is Node 3, housing the astronauts’ bathroom with suction pipes. You will also find a urine collector and water analyzer here. You guessed it right — water being a precious commodity in space, urine is purified and recycled to water on the space station. The water analyzer ensures the recycled water is germ-free and potable.

Further ahead, along with Node 3, is another port that leads to the Tranquility unit, where one can head to the Cupola. The Cupola is a dome-like structure fitted with glass windows on all sides, and it is positioned to face the earth at all times. It offers a fantastic view of our planet, showing the passing continents or brewing storms.

From Node 3, one can regain entry to Node 2 and into the Japanese module. Here, there is a specially designed equipment using which the astronauts can release small satellites to the outside space.

This assembly slides into the Airlock. With the flip of a switch, the Airlock opens to eject the mini-satellite. The ISS has launched several such satellites for scientific experiments and kept an eye on the space station’s external areas.

Although the different ports appear like a maze, a space visitor would find it easy to navigate once trained.

You are never a real tourist

Several crucial experiments are running on ISS at all times, providing valuable inputs for space science. Every moment in space is valuable, and hauling every gram costs millions. It is for this reason that there are no luxuries offered on the ISS.

The mission commander assigns even a tourist some task as per the protocol. Every individual who goes to space contributes to physiological experiments, adding to the database of how humans respond to space weather conditions.

Despite the rigors and demands of living in space, many vie to be astronauts. For the past two decades, the orbiting habitat has given humans a chance to experience life in space.

ISS remains etched in history as the glorious platform that leapfrogged human space ventures into the next era.