- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The fault in our calendars: How Pongal moved from January 14 to January 15

This year Pongal was celebrated on January 15. For most, who grew between 1940s and 2000s, it was January 14 which became synonymous with Pongal, with the festival advancing by a day occasionally during leap years. But now, Pongal falls more often on January 15 than January 14. What many may not know is that there was a time when Pongal was celebrated even on January 13. About a hundred...

This year Pongal was celebrated on January 15. For most, who grew between 1940s and 2000s, it was January 14 which became synonymous with Pongal, with the festival advancing by a day occasionally during leap years. But now, Pongal falls more often on January 15 than January 14. What many may not know is that there was a time when Pongal was celebrated even on January 13.

About a hundred years ago, Pongal was observed on January 13 in 1901 and 1905 and on the 14th in 1902, 1903, and 1904. In 2015, 2019, 2023, January 15 marked Pongal. In 2024 and 2027 too Pongal would be celebrated the same day but for the intervening years — 2016, 2017, 2018, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2025 and 2026 — January 14 is the day.

So, what brings about this change?

Short answer: incorrect computation computation of the panchāngam.

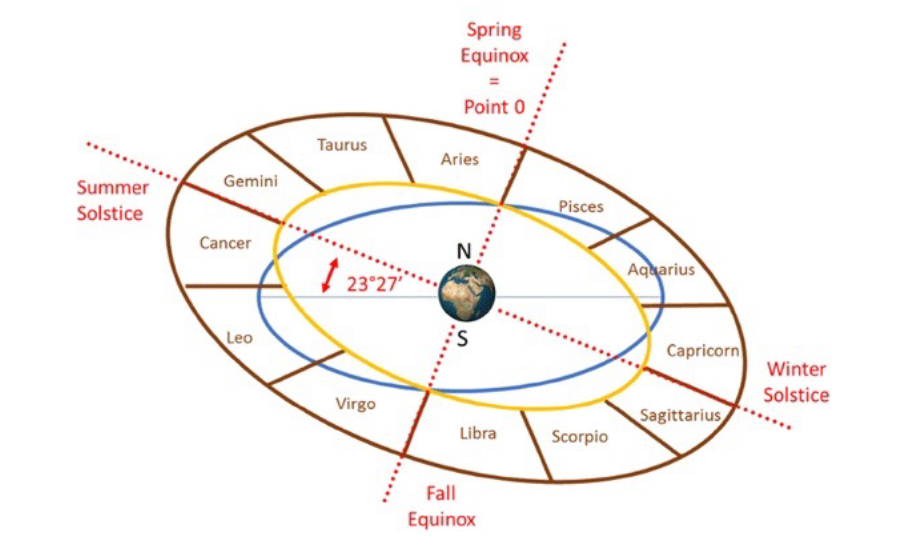

Earth orbits the Sun in an elliptical path and around its axis. Earth’s rotation axis is tilted 23.5 degrees to the plane of revolution around the Sun. Apart from these two movements, the Earth has a third movement called precessional motion. This aspect is not accounted for in the panchāngam. This is the main reason for the error in panchāngam.

Precessional motion

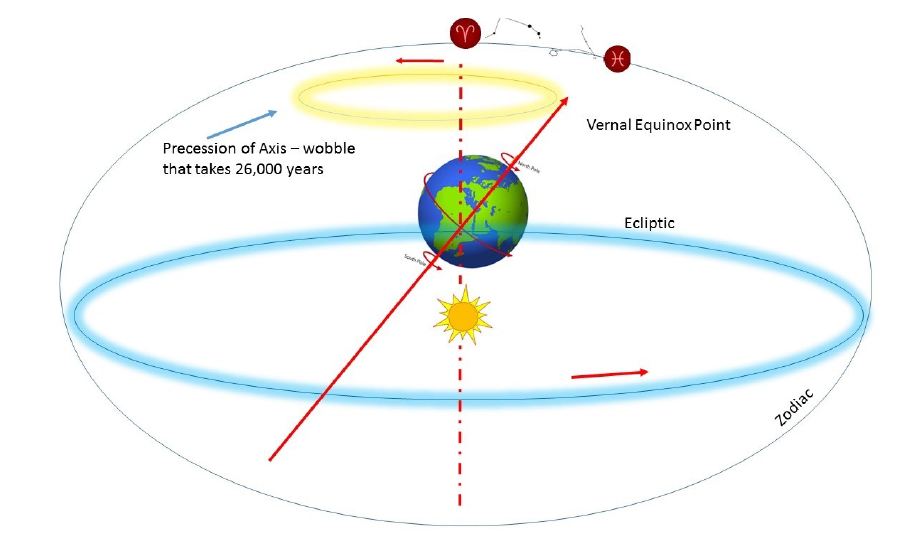

In addition to rotating on its axis (resulting in day and night) and orbiting the Sun (giving us our year), Earth has another, more gradual motion that few people know about. Like a child’s top, our planet’s axis tips around in a circle slowly as it spins. The Earth’s tipping, called the precessional motion, is relatively slow. Our planet’s axis takes over 26,000 years to make a complete circle. As a result of precession, the Earth’s axis will point in a different direction as time passes. For example, today, the Star Polaris (Dhruva tara) is near the north celestial pole. But in AD 15000, the Earth’s axis willlet us point towards the star Vega, and it will be near the north celestial pole and not Dhruv Tara.

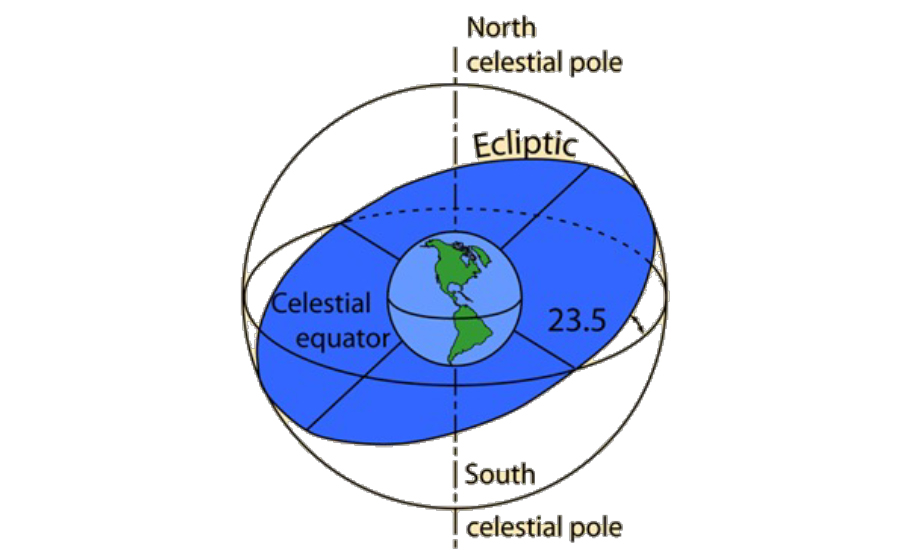

We can imagine the celestial sphere like a hollow ball surrounding all around us. Stars appear fixed on this sphere. We can project the equator of the Earth onto this sphere. This circle which is concentric to our equator is called the celestial equator. Because the axis of Earth is tilted by 23.5 degrees, the path of the Sun (called. ecliptic) on the celestial sphere will be a circle that is inclined to the celestial sphere at 23.5 degrees. There are two points where the celestial equator intersects the ecliptic, which is the path of the Sun in the sky.

It is when Earth is at the intersection points equinoxes occur — the day on which nearly all parts of the Earth experience roughly equal amounts of day and night time. Earth should return to the same juncture after one year as it revolves around the Sun. However, due to the precessional motion, Earth arrives 20 minutes early to this point each year. This means it will get to the same point about one day earlier in nearly 72 years. Panchāngams are oblivious of this aspect.

Also, there are blunders in the various parameters used by the panchāngam. Earth takes 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes 46 seconds to make one rotation around the Sun. However, according to Aryabhata, this parameter was 365 days 6 hours 12 minutes 30 seconds, and according to Surya Siddhantha, it is 365 days 6 hours 12 minutes and 36.56 seconds. These mistakes in the parameters also contribute to the mismatch between the actual position of celestial objects and panchāngam computations.

Let us consider Pongal to fall on the day when the Earth comes to that point in the sky. This means that the day of Pongal changes by about one day every 72 years. The festival was around January 14 earlier and now hovers around January 15.

Almanack error

Panchāngams do not consider precessional motion in their calculations and hence are faulty. Let us look at two examples. Pongal festival is also known as Uttarayanam.

First, what is Uttarayanam?

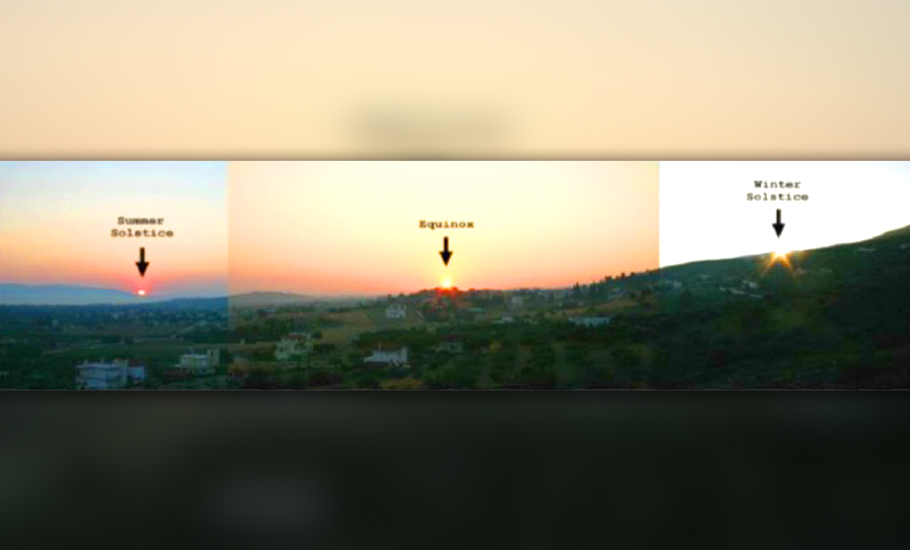

The sunrise point is not strictly due east every day of the year. The sunrise point moves north-south due to the tilt of the Earth’s axis. On Uttarayanam, the sunrise point on the eastern horizon is at the maximum southeast. On subsequent days, the sunrise point is slightly north compared to the previous day. After around six months, the sunrise point reaches utmost northeast on the eastern horizon. That day is called Dakshinayanam. After Dakshinayanam, the sunrise point appears to move south compared to the previous day. During this motion, the Sun appears to rise from due east two times a year.

The Uttarayanam or winter solstice occurs on December 20-21. However, both the Vakkya and Drigganita panchāngams mark January 14-15 as the day of Uttarayanam. Similarly, April 14 is celebrated in many parts of the country as Vishu (the day Sun rises precisely in the East). Nevertheless, the equinox actually occurs on March 21-22. In the same way, there are several grave errors in the traditional computations in Indian traditional astrology that differ from the actual position of celestial objects.

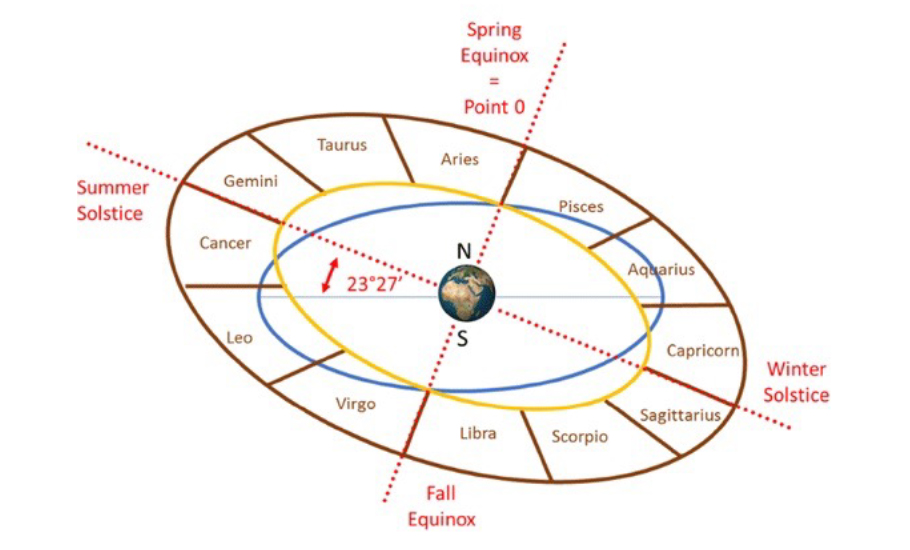

Pongal is also said to be Makar Saṁkrānti. Saṁkrānti means transmigration of the Sun from one zodiac to another and marks the beginning of solar months in the panchāngams. The ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun in the celestial sphere, is divided into 12 equal parts called zodiacs. Makar Saṁkrānti marks the transition of the Sun from Dhanu Rasi (Sagittarius) into Makar Rasi (Capricorn) on its celestial path.

Anyone with access to the internet and a software like Stellarium can easily find that on January 15, the Sun is still in Dhanu Rasi and not in Makar. In its apparent motion around the ecliptic, the Sun will be positioned in the Dhanu Rasi from December 19 to around January 19. It enters Makar Rasi only on January 20. Again a grave error.

The flaws in the panchāngams calculations are clear as crystal. Thus, the astronomical association of Pongal computed by the panchāngam are wide off the mark.

Were our ancestors ignorant?

Do the defects in the panchāngam imply the ancient Indian astronomers were clumsy? No. They were the best of their times. Naturally, we are much more precise with sophisticated telescopes and other instruments than them. Still, with the then-available crude tools, they discovered intricate motions of the celestial objects.

By making careful and methodical observations, ancient Indian astronomers such as Vishnucandra identified the precessional motion. Astronomers like Manjula CE 932 correctly argued that the Ayana–chalanam (precession of equinoxes in Indian terminology) is entirely circular, and yearly precession is about 56.82 arcsec. Manjula also stated that the precession should be carefully observed and corrected from time to time.

Astronomers like him argued for drik-tuliya (computation and observation matching). The school of scientific astronomers in India was free from astrological orthodoxy. But the obscurantist disagreed.

In his work Āryabhtīya, Aryabatta says, “from the ocean of true and false knowledge, by the grace of Brahman, the best of gems that is true knowledge has been brought up by me, by the boat of my own intelligence (svamati)”. However, obscurantists attributed the distinction of astronomers like Aryabatta, Bhramagupta Bhaskara and others to revelations. The works like Āryabhtīya and Surya Siddhantha were taken to be God’s word, revealed to them by the divinity. Once the scientific results of astronomy were deified, it became blasphemous to correct errors and improve them based on refined observations.

Let us look at Nilakantha Somayaji (1444–1544), an astronomer from Kerala who suffered at the hands of orthodoxy. He discovered the partial heliocentric solar system model much before Tycho Brahe. After undertaking methodical observation of many solar and lunar eclipses, he expounded Drgganita, a new system of astronomy that underscored the ‘observational exactitude’ (drsti-samya). He corrected the number of parameters initially computed by Aryabhatta based on accurate observations.

However, the obscurantists objected, “God Brahma was pleased by the penance of Aryabhata and so imparted to him knowledge about the astronomical parameters useful for planetary computation… Hence there is no necessity for any further experimentation, for God Brahma is omniscient and infallible.” Nilakantha Somayaji recorded this objection in his book and replied to his critics, “It is not so. Divine favour merely cleanses the intellect.

Never can God Brahma or the

Sun appear before one in person and impart instruction.” Nilakantha emphasises that the discipline of astronomy can be kept alive and accurate only by continued observation of the skies and effecting necessary periodic revision in computation.

Yet all these talks fell on deaf ears. Astrologers and panchāngam computers did not accept these scientific findings nor understand them. They continued to base their computations upon traditional texts and treatises, mainly following the Surya Siddhanta or commentaries based on it. Sometime in the middle ages, perhaps when the rigid Manuvad injunctions against blasphemy took strong roots, the tradition of evidenced-based knowledge production gave way to faith. The panchāngam mathematics ceased to take into account the development of astronomy. Therefore, it has stagnated.

Anything that ceases to rejuvenate languishes and putrefies. Perhaps, this is how once hijacked by obscurantist astrologers, panchāngam computations developed by Aryabhata, Bhaskara and other eminent ancient Indian astronomers, became moribund. Accumulating errors were overlooked, and as a result, today, Uttarayanam, Dakshinayanam, the day of entry of the Sun in rasis (Sankaranthis), the position of planets, and so on are at variance with the actual status of celestial objects.

So much so, during the partial solar eclipse on October 25, 2022, at Chennai, the maximum eclipse occurred at 5.42. Still, unabashedly, Vakkya panchāngam and Drik panchāngam computed it to be 4.18 and 4.19, respectively.

But it isn’t just the Indian panchāngam which is out of step with the rhythm of celestial objects?

The European calendar, too, was marred by the precessional motion. The Julian calendar took the year to be exactly 365.25 days long, while the actual length is 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes 46 seconds. Due to this error, the spring equinox drifted from its nominal March 21 date in the Julian calendar. This caused difficulties in the calculation of the date of Easter. Noting the anomaly between the Julian calendar and actual astronomical positions, Pope Gregory XIII reformed the calendar in October 1582 by removing 11 days. Thus in the new Gregorian calendar, Thursday, the October 4, 1582, was followed by Friday, October 15, 1582.

Indeed the obscurantists in Europe objected to this reform. Only a few countries accepted this readily. Russia implemented the change only after the Soviet Revolution of 1917; that is why the ‘October Revolution’ is celebrated on November 7 every year!

About 2000 years ago, the day of Pongal was the day of Uttarayanam. However, due to the precessional motion, over the years, the day of Pongal and Uttarayanam diverged at the rate of about one day in 72 years. About 50 years ago, during my childhood, Pongal usually fell on the 14th of January, 25 days after Uttarayanam on the 21st of December. With time, the deviation has increased by a day, making the Pongal fall on the 15th of January.

After hundred years, if no reform is undertaken, the Pongal will shift to the 16th of January. Moving a day later, every 70 years or so, about 2000 years later, the Pongal and Uttarayanam will coincide.

After all, a clock that is not working will tell the correct time twice a day.