- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Teetering on the edge of extinction, the Koraga tribe remains unseen

With a tripundra tilak on the forehead, broken in the middle by the imagery of a third eye, the much-revered Koragajja looks at his worshippers with raised eyebrows and widened eyes, and a chin outlined by a flower garland. The deity is ubiquitous in the coastal Karnataka districts, including Dakshina Kannada and Udupi. He resides in homes in the form of idols and also travels across stuck on...

With a tripundra tilak on the forehead, broken in the middle by the imagery of a third eye, the much-revered Koragajja looks at his worshippers with raised eyebrows and widened eyes, and a chin outlined by a flower garland. The deity is ubiquitous in the coastal Karnataka districts, including Dakshina Kannada and Udupi. He resides in homes in the form of idols and also travels across stuck on car stickers showing the faith people place in the deity, considered to be a form Shiva.

Koragajja is the ‘spirit’ of Tulunadu and almost everyone seeks his blessings to ease their hardship. For the uninitiated, the Tulunadu region comprises the districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi in Karnataka and the northern part of Kasaragod district of Kerala up to the Payaswini river.

While Koragajja is revered even beyond the region of Tulunadu, the Koraga community to which the adivasi deity is said to belong to, is facing an imminent risk of extinction due to years of neglect, discrimination and exploitation.

The Koraga population over the years has seen a rapid decline with the tribal community being identified as one that is fast moving towards extinction. The Koragas are, in fact, classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG).

The Koragas have a rich history not just in Tulunadu, but even beyond, though the versions of this history differ.

According to one popular version, it is said that the land of Tulunadu came to be ruled by Koraga king Hubashika after he defeated Mayuravarma and established the Koraga kingdom.

Later, Hubashika was killed stealthily by Kadamba dynasty emperor Mayura Varma’s son Lokaditya. Legend has it that when Hubashika’s land came under attack from the invading forces of Mayur Verma, he fought back hard, driving the Kadambas out. Left with a bruised pride, the Kadambas plotted revenge. Lokaditya invited Hubasika for peace talks with the prospect of a marital arrangement. But Hubashika, along with his nephew, was held captive and killed.

With their king dead, Koragas took shelter in forests and came to depend on forest byproducts for their livelihood.

But in his novel Kotta, former Karnataka chief minister and Union minister M Veerappa Moily writes that king Hubashika was killed by one Angara Varma, king of Manjeshwar (now part of the region in Karnataka bordering Kerala).

Some historians also say that Hubashika invaded the coastal areas of Karnataka at a time when Jain king Lokadiraya was ruling Banavasi.

According to Colonel Mark Wilks, a historian who has done extensive work in Mysore, the incident took place in 1450 CE. Hubashika mobilised an army of Koragas and invaded Mangalore and Manjeshwar areas, established his kingdom and ruled for over 12 years.

According to some experts, the word Hubashika may have its origins in the Japanese language. Hubashi in Japanese means ‘invading the forest’. Some also believe that the Koraga community may have a connection with the ‘Siddi’ tribal community, which hailed from southeast Africa and came to India during the time of Portuguese rule. Some others say that they might have arrived from Ethiopia and come to India and served under Mughal kings as soldiers.

Describing their spread, in his accounts, traveller and scholar Ibn Battuta mentioned that he found ‘Habashis’ working as soldiers in north India and as sailors in Sri Lanka.

He writes that one Mallik Sarvar, a Habashi, announced a separate administration in present-day Jaipur. Those found in south India are said to have been brought there from West Bengal by rulers of the Hussain Shahi dynasty in 1456.

The people of the forest

While there are many mentions of Koragas (also referred to as Habashis) in history, indicating that they were spread far and wide, their numbers today tell a sordid story of their plight.

“Our community lived happily in the forests, thriving on minor forest produce. They ate tuber yams, fibre and roots. But once they were thrown out of forests, following the Forests Act, they began to perish as they were not adept in surviving outside the forests and successive governments never focused on their well-being,” Baabu Koraga of Nelyadi in Dakshina Kannada told The Federal.

The Koragas follow a patrilineal system and practice endogamy with regard to their three main subdivisions, the Sappina, the Ande and the Kappada Koraga. While each of the three subdivisions are further divided into clans known as Balis, the Koragas do not marry within their own clan.

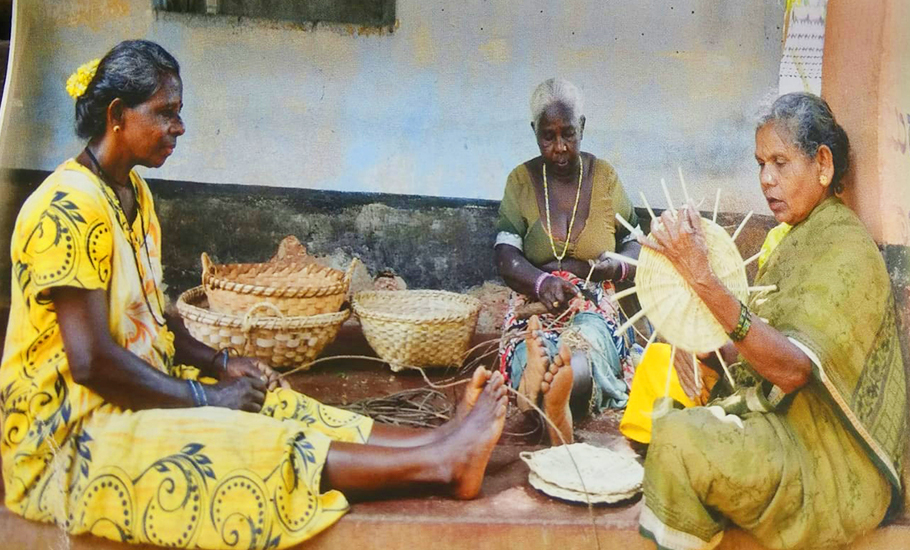

Members of the community mostly make a living by weaving baskets. The fact that they continue to follow pre-agricultural practices and practice endogamy makes them vulnerable. Economic backwardness and low literacy rates increase the risk of exploitation for them.

So acute has been the discrimination against Koragas that they widely were subjected to the inhuman Ajalu practice. The government of Karanataka defined the practice as “differentiating Koraga people and persons belonging to other communities, treating them as inferior human beings, mixing hair, nails and other inedible obnoxious substances in the food and asking them to eat that food and to make them run like buffaloes before the beginning of Kambala”. The inhumane practice was banned in 2000 under the Karnataka Koragas (Prohibition of Ajalu Practice) Act, 2000.

Despite the ban, there have been several instances in the recent past where Koragas have been humiliated and subjected to such inhuman practices.

What continues to hurt the community is that neither the Koraga tribe nor their language, also known as Koraga, has got due representation in Karnataka. In 2011, as many as about 15,000 out of 23 lakh people in Dakshin Kannada and Udupi districts of Karnataka spoke the language, which was described as a ‘secret Dravidian language of Madras’ by Irish administrator and linguist in British India George Abraham Grierson. Grierson also said that Koraga could be a dialect of Tulu.

The Koraga language hasn’t been recognised by the Sahitya Akademi nor is there any centre for development of the language. It doesn’t even have a sub-department under an existing language centre – be it Tulu or Kannada – in the district.

The systemic oppression and discrimination has left the community traumatised and lacking in confidence.

“Members of the Koraga community are ostracised and discriminated against even now. This leaves them feeling inferior and shy, preventing them from joining the mainstream,” says Sabitha PG, assistant professor at the Department of Sociology at Mangalore University, who did her PhD research on the Koraga community.

Even though some NGOs have tried to help the community, the help has proved inadequate in the absence of any sustained governmental intervention.

“For decades our families have been considered less than human. We have been subjected to abuse and exploitation, made to eat food mixed with nails and hair. Our wounds are deep. Lack of education prevents us from making a decent living. NGOs help us get access to some help here and there, but it is inadequate,” says Anitha Koraga, who lives in Belthangady.

Members of the civil society also admit that they have not been able to make a significant impact because of reasons of social and cultural moorings of the Koragas and the apathy of successive governments.

“The community has suffered unimaginable cruelty and discrimination, including untouchability and forced labour. Even though several NGOs are working to help them out of this situation, the lack of educational opportunities and basic facilities continue to strike hard at their very existence,” says Ashok Kumar Shetty of Samagra Grameena Ashrama.

It is this existential threat looming over the community that should worry everyone.

Drastic decrease in population

Before India achieved Independence, the population of Koragas was around 77,000. In 1981, it was 23,000. By 1991, it had shrunk further to 22,900 and in 2001, only 18,000 were left. The population of Koragas in 2011 stood at 15,991, and reached 13,500 in 2021, as per an interim survey by the state government.

In Karnataka, there are around 52 tribal communities, while the population of most tribal communities is increasing, it is the Koragas who are facing extinction.

“Many Koragas are dying of Sickle-cell disease, excessive consumption of alcohol, anaemia, and various other poverty-induced illnesses. Moreover, inbreeding has also led to a weakened gene pool for the community,” Dr Sabita, who has done extensive research on the Koragas, tells The Federal.

“The Koragas are yet to understand that endogamy is proving fatal. The government has failed in sensitising the community to the problem,” she adds.

A visit to any Koraga colony shows malnourished children living in unhygienic conditions. Health officials, who did a survey on the housing status of the Koraga community people, made startling revelations about their squalid conditions. Many of the Koragas have no BPL ration card and depend on their meagre earnings from making cane baskets. Some work as daily wage labourers to make ends meet.

“Their condition is pitiable. If the government does not act quickly, it will be responsible for the disappearance of a whole community from our country,” says one of the officials who wishes to remain unnamed.