- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

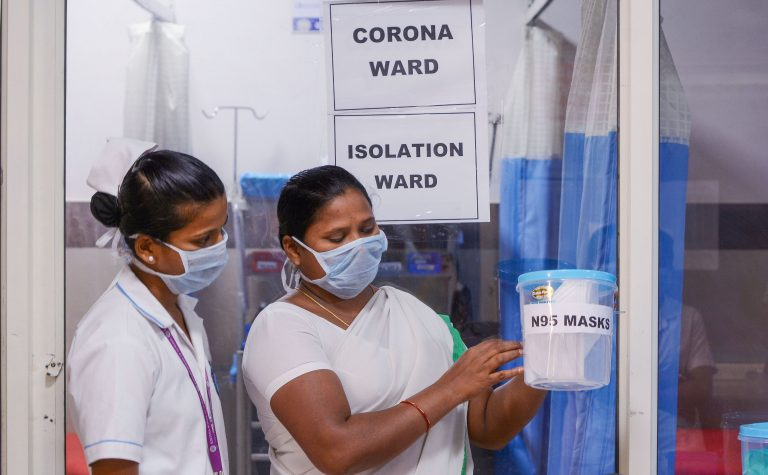

Taken for granted, nurses are overworked and underpaid

“I mutter a prayer every time I enter the COVID-19 ward in the hospital,” says Saroja (name changed), a 49-year-old nurse on COVID-19 duty in a tertiary government hospital in Chennai. The fear of contracting the virus lingers although she has 25 years’ experience and like nurses across the country, she has gone through the drill about precautions to be taken for coronavirus. And this...

“I mutter a prayer every time I enter the COVID-19 ward in the hospital,” says Saroja (name changed), a 49-year-old nurse on COVID-19 duty in a tertiary government hospital in Chennai.

The fear of contracting the virus lingers although she has 25 years’ experience and like nurses across the country, she has gone through the drill about precautions to be taken for coronavirus. And this is not her first tryst with infectious diseases.

“I have spent many years taking care of dengue patients in the fever ward. But nothing can be as distressing as this,” she says, adding that nothing can instill confidence in her. “I inadvertently think about my daughters, my husband and my family — what will they do if I get infected?”

When the first case in the city was reported and the patient was admitted to the hospital, Saroja remembers the anxiety nurses like her felt. “We had seen the havoc the infection wreaked in other countries. Naturally, I was very worried about how it would pan out here,” she adds.

Saroja, who had nurtured the dream of being a nurse since childhood, says now she can feel her heart palpitate when she enters the COVID ward in the protective overall. “I can feel the heat in my body, as long as I wear it.”

The personal protective equipment (PPE) is meant to protect doctors, nurses and healthcare workers against getting infected.

Infected despite PPE

“But despite the PPE, one of my colleagues who was posted in the room next to mine, has tested positive,” Saroja says. “I spoke to her the day her result was positive, she was as cool as a cucumber. But the next day, she broke down and cried over the phone. So, I have this uneasy doubt in my mind: will I be next?”

Her colleague was not the first one. At least 35 nurses in Delhi and 27 in Mumbai, besides one in Kerala, have been infected by COVID-19. Although no deaths have been reported of nurses, there have been at least two deaths of doctors due to coronavirus in Chennai.

Nurses and doctors also have to suppress their stress arising due to wearing the PPE continuously for hours, without food or toilet breaks as they have to dispose of the PPE once they take it off, which is usually done after a shift ends.

“The problem is that with the limited number of PPE available, I have to control my urge to visit the washroom, as we cannot afford to use more than one while on duty on a single day,” Saroja says.

But despite the risks, nurses continue to serve patients.

Joy Kezia, chief of nursing, Fortis Malar Hospital, says, “Some of them told me in the beginning that their parents and families are worried about them and they want to opt out of the duty, but that is part of parental concern. However, they have all continued to serve happily and call back during the quarantine period to tell us they want to rejoin duty soon, as they are bored,” she says.

Managing patients

Saroja too says that she cannot afford to show her fear in front of the patients. “I spend the whole day with them. Some are bold, some need assuring words and some need our prayers. One patient, who is calm and composed on the day of their diagnosis, is a bag of nerves the next day. I always tell them that they will be fine soon and tell them to believe in God and their prayers,” she adds. “Giving them medicines is only a fraction of the job, the rest is all about counselling them in our own capacity.”

“The anxiety continues for nurses in emergency rooms and triage and a part of it is also because some patients are not telling us the truth about their history,” says Joy.

Hospitals like Fortis have made it mandatory for testing every patient getting admitted for any procedure — elective or planned — while they have closed the outpatient department.

Poor treatment, no dignity

Nurses in public healthcare facilities have been asked to stay in the hospital quarantine after a seven-day duty, but they are not being treated well, complains Saroja.

“I have been hearing from my colleagues that they wait for a long time for morning coffee and meals. I recently came across news of a hotel providing food for hospital staff on COVID-19 duty. Why can’t such things happen here in Chennai?” she asks.

Not just in Saroja’s hospital, but the secondary treatment meted out to nurses is the harsh truth across the country. According to reports, nurses and ward boys were treated secondary to doctors and were getting poor quality or no PPEs while serving in a COVID ward.

A nurse who is a member of the United Nurses Association (UNA) in New Delhi on condition of anonymity says that while doctors are taken care in luxury hotels, nurses settle for mediocre arrangements.

“Nurses including women staff are expected to be sharing a common dormitory with limited bathrooms,” she says, before adding that they had to fight with managements of many hospitals for some alternative arrangements with moderately better facilities to be arranged. “The Delhi government also agreed to provide nurses with food,” she adds.

Joy too says that they get complaints about nurses feeling nauseated because of the negative pressure in the rooms, with no windows or air conditioning.

Staff shortage, poor pay

Nurses are also stressed and overworked because of staff shortage and high attrition which is a result of poor facilities and working conditions. As per the Indian Nursing Council, there were 30.4 lakh nursing personnel in the country as of December 31, 2018, of which about 20 lakh were estimated to be active, the minister of state for health Ashwini Choubey told Rajya Sabha in July 2019.

However, this ratio comes down to one nurse for 675 Indians, and is much lower than the 3:1000 (or 1:333) prescribed by the World Health Organisation. According to Dr Devi Shetty, chairman of Narayana Group of Hospitals, India would need about 60 lakh more nurses by 2030.

Joy says that the fact that they are not paid well and not accorded dignity are interrelated.

The Supreme Court had in 2017 set the minimum salary for nurses at ₹20,000 per month, which Kerala began following from last year while the rest of the country is yet to implement it, points out the source from UNA. This after most do a four-year BSc Nursing course which costs almost ₹6 lakh.

“There is no gradation for nurses in India. The difference in pay between sectors is not much, be it the Centre, state or private,” Joy points out.

Migration to greener pastures

The nurse from UNA, who originally hails from Kerala, says because of this, you will find nurses migrating to better cities like Delhi, Mumbai or even abroad for better opportunities.

According to a study, despite the extremely low nurse to population ratio in India, nurses are encouraged by certain training and recruitment agencies to move abroad, especially from Delhi, Bangalore and Kochi to the US, UK and the Middle East, enabled by a well organised and profitable system.

Those who stay behind are often overworked and continue to toil because they cannot afford to give up the jobs, says Joy.

“At the end of this pandemic, I hope it is not assumed that they can be continued to be treated with disregard as they will serve come what may,” she says.

For now, as they serve in hostile and discriminatory conditions, psychological counselling has been provided to them.

“Some of them have been attacked by police or neighbours and have faced discrimination too in their localities. We have psychologists on board to address their queries and fears, and a helpline has been set up for this purpose,” adds the nurse.

Saroja says that in her locality, people treat her with a lot of respect after she has begun working in the COVID-19 ward. “But some also see me with fear, as they think I will end up infecting them,” she says.

The regard and concern for nurses remain as mere tokenism, they say. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared the year as ‘Nurses and Midwives Year’ and May 12 is observed as World Nurses Day every year.

Joy asks, “How about giving them the dignity and respect throughout the year, instead of making it a ceremony for just a day?”

(This story is part of a series on frontline personnel in the fight against COVID-19. You can read the other stories here)