- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Delta of decay: Human folly, nature’s fury ravage the Sunderbans

For nature’s fury, people of the delta in Sunderbans in West Bengal could not escape their share of blame and the worst is yet to come, believe many.

A distance of 108 kilometres separates the Sunderbans from Behela, the oldest residential area of Kolkata today known more for being the home of BCCI chief and former Indian cricket captain Sourav Ganguly. This bustling locality in south-west Kolkata was once considered to be part of the Sunderbans mangrove forest, inhabited by farmers, fishermen and honey-gatherers. That was in the 12th...

A distance of 108 kilometres separates the Sunderbans from Behela, the oldest residential area of Kolkata today known more for being the home of BCCI chief and former Indian cricket captain Sourav Ganguly. This bustling locality in south-west Kolkata was once considered to be part of the Sunderbans mangrove forest, inhabited by farmers, fishermen and honey-gatherers.

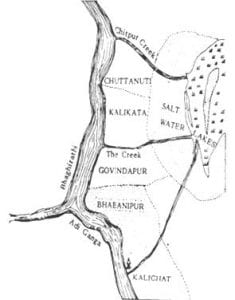

That was in the 12th century, when the Pala kings ruled Bengal and the river Ganges had a different course. It flowed through Kalighat — not far from Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s residence — to reach Gangasagar, the confluence of the Ganga with the Bay of Bengal.

The once mighty river has now turned into a narrow sewer; it’s still called ‘Adiganga’, or original Ganga, though.

“’From the fifteenth century,” wrote the geographer RK Mukherjee in his book The Changing Face of Bengal: A Study in Riverine Economy, “man has carried on the work of reclamation here, fighting with the jungle, the tiger, the wild buffalo, the pig, and the crocodile, until at the present day nearly half of what was formerly an impenetrable forest has been converted into gardens of graceful palm and fields of waving rice.”

Since that ancient past, the face of Sunderbans has been constantly changing due to ravages of nature and depredations of humans.

Coming home to devastation

As he stepped into Sandeshkhali on returning from Kerala where he was working as a worker in a road project, Tapas Sardar did not miss the change the recent Cyclone Amphan had inflicted on the island he grew up in.

He noticed the mangled wrecks and his heart sank immediately. Over a crackling phone call before boarding the train home, he had promised his wife not to step out of the island ever again for livelihood. But then Sardar can hardly control fate. Almost all the trees in the vast swathes of the island have turned yellow or red. Even a few species of mangroves have started changing colour, shedding evergreen shade.

Sardar is obviously not the only one to notice the alarming phenomenon.

“Yes, we have noticed that after Amphan almost all trees such as mango, neem, banyan are turning yellow or red. Leaves of some mangroves too turned reddish and yellowish. We have never seen anything like this before,” said Sukumar Mahato, MLA from Sandeshkhali in North 24-Parganas district.

Principal chief conservator of forests (PCCF), West Bengal, Ravi Kant Sinha told the media that this could be due to an increase in salinity of water.

Ingression of sea water into their land is the biggest agony for any resident of this riverine deltas, one of the largest in the world, almost entirely created by deposition of silt brought in by Ganga, Brahmaputra (called Jamuna in Bangladesh) and Meghna.

The Unesco world heritage site is an archipelago of 200-odd islands separated by about 40 interconnected tidal rivers, creeks and canals spread across India and Bangladesh. The Indian side of the delta comprises 102 islands spread over 9,600 sqkm.

On the banks of an extensive network of estuaries, criss-crossing rivers and creeks nestle 54 islands having human settlements, with a 3,500-kilometre-long embankment, a large stretch of which was built during the British rule some 250 years ago to prevent saline water reaching the fields.

Swamped by humans

As one travels further south, the profile of the area changes into a dense forest of mangroves impenetrable to human beings, barring a few desperate honey gatherers and woodcutters. Walking onto many of these islands is almost impossible owing to the dense jungle and prong-like breathing roots of trees that pierce upwards out of the ground. This is the territory of the famed Royal Bengal Tigers, whose number in the area has climbed to 96, up by eight from last year, as per the latest count.

Although the topography of the region by and large is not conducive for human habitation, the hamlets spaced around the edge of the forest is densely populated being home to over 4.44 million people as per the 2011 census.

Located at the mouth of the Bay of Bengal, a frequent epicentre of the origin of cyclonic depressions, the delta is frequently devastated by cyclonic storms. A catalogue of tropical cyclones shows that over 70 per cent of the deadliest tropical cyclones in world history have been Bay of Bengal storms.

Creation and destruction is the cyclical pattern of people’s lives in this region. An archaeological find a few years ago indicates the existence of an ancient civilisation in the mangroves dating back to the Mauryan period (322-185 BC).

The cycle of life and devastation

In folklore, the history of the Sunderbans area can be traced back to 200-300 AD. In Bengali folk epic Manasamangal, the earliest of the mangal kavya (a group of Bengali Hindu religious texts) composed between the 13th and 18th centuries, some passages were set in the Sunderbans.

What intrigued historians and archaeologists is the mystery of how civilisation suddenly disappeared, only to be repopulated again in the 18th century after the British administration built the embankment to keep the saline water at bay during high tide to encourage human settlement.

The 250-year-old embankment is no longer proving to be an effective barrier against cyclonic storms.

A large stretch of the mud embankment was breached when Cyclone Aila hit the delta in 2009, submerging human habitats under brine water, rendering swathes of agricultural track uncultivable, triggering a large scale exodus of people from the area to major urban centres of the country for jobs.

Sardar, 44, was among those who were forced to migrate to the cities for livelihood as their land had become unfit for agriculture in the aftermath of the storm surge.

On an average, about 200 people had been leaving for the mainland each day with their belongings and livestock, Down to Earth had reported after the cyclone, adding the migration had increased threefold since Aila struck.

A study by DECMA (Delta Vulnerability and Climate Change: Migration and Adaptation), found out that 64 per cent of the migration between 2014 and 2018 from the Sunderbans was triggered due to economic distress caused by the lack of agricultural opportunities.

The Amphan which made landfall on May 20 breached the embankments in 32 places, damaging nearly 17,800 hectares of agricultural lands, with saline water from seas entering the farms. An estimated 1.08 lakh farmers have been affected.

Sunderbans Affairs Minister Manturam Pakhira described it as a “black day” in the history of the delta.

In search of greener pastures

The worst is yet to come, fears Sardar as he scans the horizon laced with ‘decaying’ trees.

The increase in salinity means several more years of non-farming activities. The salt-tolerant paddy the state government proposed to grow in the affected islands did not enthuse locals such as Sardar.

Cultivation of one crop a year would not fetch enough income for his family to prevent him from migrating.

“Generally we go out to work in October-November and return to the village in May-June to grow paddy during monsoon,” Sardar said. This year he was planning to sow pulses as well in the winter and also grow vegetables so that he did not have to look for a job outside the island.

The colour of trees, however, is compelling him to rethink. “If this is the condition of mangroves, surely there will be no meaningful farming at least for another one to two years,” he added.

His concern is echoed by a member of South 24 Parganas Zila Parishad, Animesh Mandal. “The Sunderbans was just coming out of the devastating impact of Aila on its agriculture sector. Now this Amphan has again pushed us back,” he said.

The people of the delta though cannot escape their share of blame. The very mangrove forests which act as a natural flood barrier, protecting the coastal population from the devastating impact of cyclones, has been denuded, making the villages more vulnerable to storms.

Felling of trees for illicit logging, infrastructure development, construction of hotels and resorts, rapidly expanding shrimp farming and fisheries are taking a toll on the mangroves that acts as a wind barrier.

The mangrove cover depleted from 1,038 sqkm in 2011 to 999 sqkm in 2017, according to the state of forest report of the Forest Survey of India released in 2017. Moderately dense forest cover shrunk from 881 sq km to 692 sq km during the same period, according to the same report.

‘Top-dying disease’, which affects Heritiera fomes — a species of mangrove tree known as “sundari” — from which the delta derived its name, is also afflicting the region’s forest cover.

As the delta dies a slow death, Sardar contemplates again a life beyond Sunderbans.