- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Struggles of African-origin Siddis expose India’s ‘black lives matter’ pretence

Most Siddis still reside in the forests, surviving on agriculture and minor forest produce. One of the reasons for that, according to the community, is racial discrimination.

About 420 km north-west of Bengaluru, in Yellapur, Haliyal and Mundgod regions of Uttara Kannada in Karnataka reside the Siddi tribal community of African origin. Neglected and isolated for decades, their gradual emergence into mainstream society got a boost recently with the nomination of a member into the Karnataka Legislative Council of Karnataka. Shantaram Budna Siddi, one of the first...

About 420 km north-west of Bengaluru, in Yellapur, Haliyal and Mundgod regions of Uttara Kannada in Karnataka reside the Siddi tribal community of African origin.

Neglected and isolated for decades, their gradual emergence into mainstream society got a boost recently with the nomination of a member into the Karnataka Legislative Council of Karnataka.

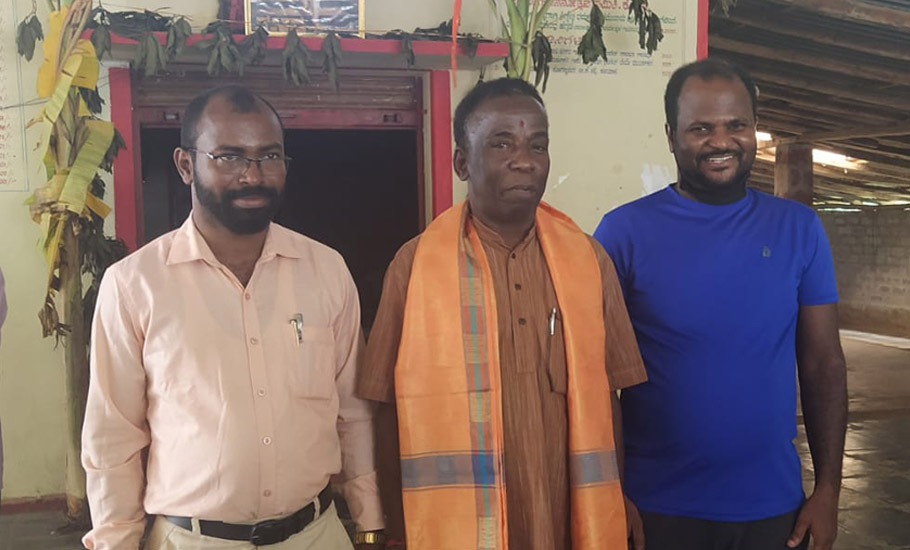

Shantaram Budna Siddi, one of the first from his community to graduate in 1988, has been involved in social service for the upliftment of his community.

His nomination to the Council by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came as a surprise even to him.

“Like all others, I too got to know about my nomination only after it was done. While it’s a matter of pride, the role also comes with additional responsibility. Now I have to not just fight for my people, but also for other communities who are marginalised,” Shantaram says.

Before he became a legislator, Shantaram was for long associated with the Vanavasi Kalyan Prakalpa, a tribal welfare initiative of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

That link aside, his community is largely cut off from the mainstream. Most Siddis still reside in the forests, surviving on agriculture and minor forest produce.

Racial discrimination continues

One of the key reasons for that, according to the community, is racial discrimination.

Nagarathna Siddi, one of the few who ventured out of the forests and became an anganwadi school teacher in Hasanagi village, says it’s not easy for a Siddi to climb up the ladder, whether with education or jobs.

One haunting question that she always encounters is — “Why do you look different?”

“People refer to us as Africans because we have curly hair and other similar facial features. But we are very much Indians. We are born and brought up here. We follow the customs and practices of Indian tradition. So why see us differently?” she asks.

Siddis, who are descendants of Bantu people of East Africa, were largely brought to India as slaves by the Arabs and the Portuguese between the 16th and 19th centuries. Researchers say when the Portuguese brought them as slaves to Goa, many escaped from the increasing atrocities of the colonisers and moved into the interior forest regions in Uttara Kannada.

With no option to return, they lost their links with their roots and ended up assimilating with their present surroundings over the years. As per the Census 2011, there were 10,477 Siddis in Uttara Kannada. Overall, there are an estimated 30,000 Siddis, mostly confined to dense forest ranges of Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh across India.

While the tribal community from Uttara Kannada got included in the official Scheduled Tribe list in 2003, the benefits did not percolate to all.

“We need equality. People still see us as inferiors. Probably only 10 percent of the population is out of the forest. Unless a favourable environment gets created, people will not come out to explore the new world,” Nagarathna says.

She worked as a maid outside the forest area and that made her get into high school. She worked in the morning before going to school.

People fear to come out of the villages because of the discrimination and racial abuses, she says.

For equality and rights

The fight for equality and rights is on Shantaram’s agenda. But his priorities will be education, tribal and forest rights, land transfer issues and protecting their unique culture.

The high school dropouts among the children from the community need to be addressed so that they go back to school.

On land and forest rights, last year, several Siddis complained that the government rejected their right to live in the forest under the Forest Rights Act. Many do not have documents. The government needs to re-conduct land surveys and take people into confidence, he says.

“Just because I am now politically active and that set the stage for us to be in the limelight doesn’t mean I want my people to come out. We need to improve their lives in such a way that they coexist with nature and not completely migrate,” he adds. “We can still impart education and give electricity to all in the forests.”

And for that, he seeks a special treatment to forest dwellers. “For instance, if 18 electric poles have to be erected to give electricity to 100 houses in a town, we may require to erect 100 poles to get 18-20 houses electrified in villages (in forests). So, one cannot treat all on the same lines like in the plains,” he says.

Shantaram, however, takes pride in the fact that Siddis do get recognised in sports due to their natural athletic prowess.

“While it is encouraging to get some recognition, we still have our own songs, dance and art forms which we want to retain and protect. The development process should not kill those,” Nagarathna says.

Shantaram wants the government to include his community in the planning and decision making of development projects in their region. “Otherwise they often tend to lose out.”

He is confident that a forest (Siddi) kid will know more species of trees than those who decide for them (government officials).

So far there’s unity — Hindus, Muslims and Christians — all within the community live peacefully in harmony with nature. That unity should be retained, he says.

But creating a favourable environment is somewhat dicey as the ruling BJP has been weakening the environment and forest related laws.

First lawyer and cases galore

Jayaram Siddi, the first lawyer from the community who graduated in 2011 and moved to Bangalore, welcomes Shantaram’s nomination, and says the community neither has the money to spend on elections nor is their voter base so big that they can influence other communities to vote for them.

Jayaram’s parents still live in the forests in Yellapur. He says they haven’t even visited Dharwad in north Karnataka, which is about 80 km from their place.

While he feels he needs to get back to the village and help his community, currently he’s focussed on gaining legal experience in Bangalore.

Jayaram, who’s grateful to the BJP government for giving them a voice in the political arena, feels there is still a lot to be done to improve the lives of his people.

“Many people still do not have title deeds. That needs to be sorted out. Also, the funds allocated for our development are never utilised properly. It gets looted by those who are rich and corrupt,” Jayaram says.

When asked what are the cases that he encounters from his community people, he says land issues and false crime cases dominate his case list. “False cases against our community members, particularly, equating us to (Nigerian) criminal gangs are common,” he says.

“Some come all the way to Bengaluru to get their land issue sorted. They are so poor that I have to pay them money to go back. I really want to serve them in the village.”