- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Space: The new wild wild west

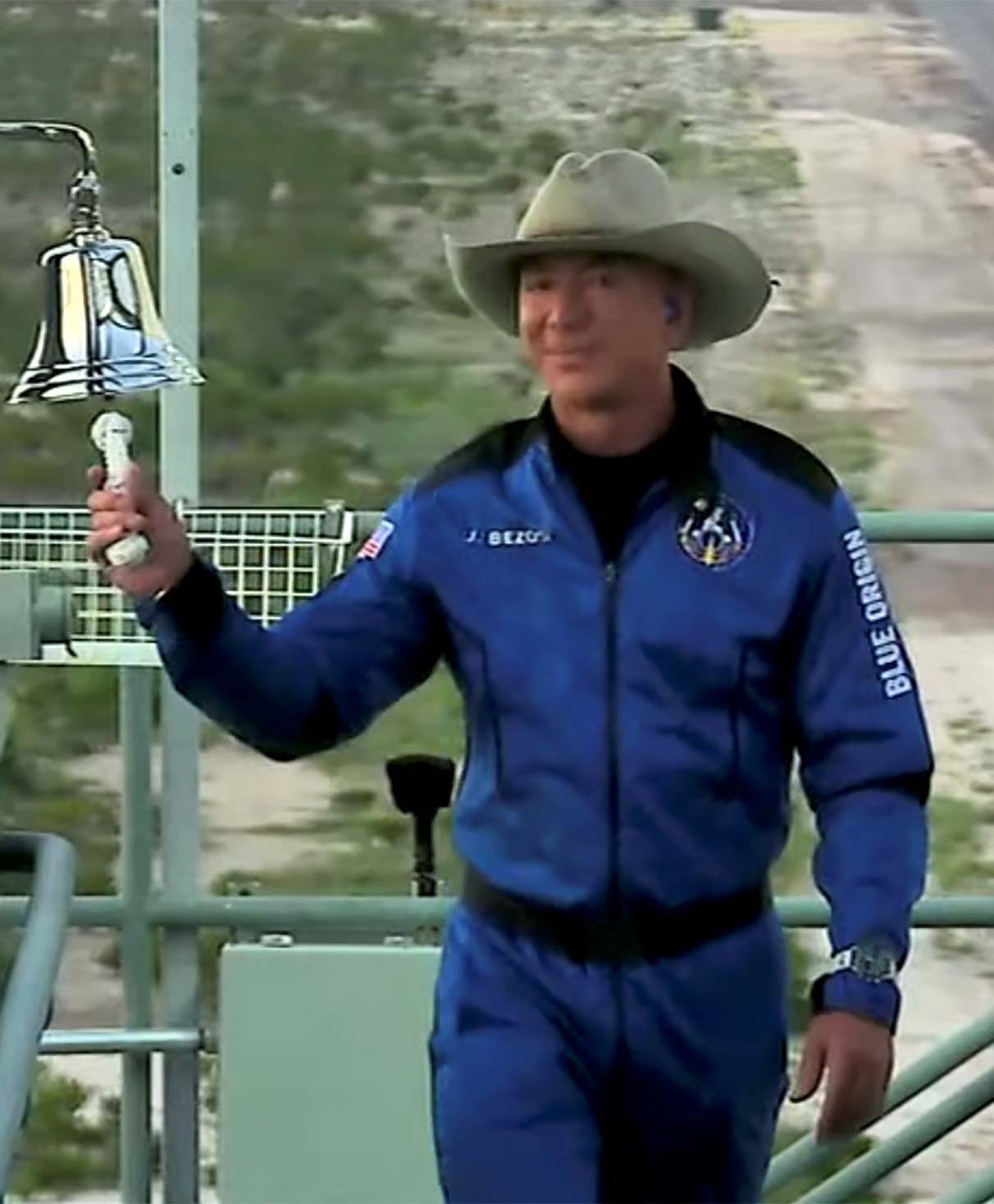

The world watched with awe the suborbital flight of Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo Unity by British business magnate Richard Branson and his team on July 11, 2021. A few days later, Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket took Amazon founder and Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos and his small team just past the edge of space. Heralded as the birth of NewSpace, these ventures by starry-eyed new...

The world watched with awe the suborbital flight of Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo Unity by British business magnate Richard Branson and his team on July 11, 2021. A few days later, Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket took Amazon founder and Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos and his small team just past the edge of space.

Heralded as the birth of NewSpace, these ventures by starry-eyed new age billionaires, including Musk’s SpaceX, are seen as the advent of space tourism as a commercial venture. With a ride costing about USD 250,000, it is reported that already 600 firm bookings have been made by these three enterprises.

Cheap thrill

Neither Branson nor Bezos is the first tourist to space. Toyohiro Akiyama, a journalist from the Tokyo Broadcasting System, spent seven days aboard the Soviet Union’s Mir space station, about 500 km above the earth, for a fee of $12 million from his employers. The fete of Branson and Bezos pale in comparison.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Roscosmos entertained wealthy space tourists for a ride at the cost of about USD 20 million for hitching a ride on a Russian rocket to the International Space Station (ISS). So far, seven tourists have paid their way to the ISS on Russian craft.

Virgin Galactic Unity reached an altitude of above 80 km, which the Federal Aviation Administration of the US classifies as ‘space’. In contrast, Blue Origin crossed the so-called Kármán line at an altitude of 100 km, recognized by the Outer Space treaty.

Passengers of both the ships will earn astronaut wings for their suborbital flight. Still, their entire space flight lasted for about 10–12 minutes, and they would have experienced weightlessness for a measly 2–3 minutes.

For ‘real’ space adventure, both the Roscosmos and NASA have propositions. The cash strapped Roscosmos is planning a slew of commercial space travel to the International Space Station and the first tourist spacewalk at the station in 2023. NASA will soon market ISS for roughly $35,000 per night and an additional $50 million for a seat on the space flight.

NewSpace is less about space tourism or selling bread and breakfast on the ISS; it’s all about mining celestial bodies for precious metals and building a space economy. If the American pioneers risked the frontier trials and sought virgin land, a generation of NewSpace entrepreneurs are launching rockets and satellites to reap profit. They want to inundate the planet with cheap mobile phone signals, manufacture novel materials in the zero-gravity of space stations, and dream of harvesting water from the Moon and precious metals from asteroids. Outer space is the emerging new frontier.

The rare earth frontier

Nicknamed ‘vitamins of modern society, their unique properties, particularly in terms of magnetism, temperature resistance and resistance to corrosion make rare earth elements (REE) indispensable for manufacturing from flat TV to smart missiles. Video screens from smart TV to mobile phones need europium; it is also crucial for the manufacture of nuclear reactors’ control rods.

Smartphones, televisions, lasers, rechargeable batteries and hard drives need neodymium magnets. Petroleum refining requires Lanthanum-based catalysts, and Cerium-based catalysts are used in automotive catalytic converters. Holmium has the highest magnetic strength and is used in creating powerful magnets.

From magnetic resonance imagery (MRI) to genetic screening tests, radar detection devices, highly reflective glass, computer memory, high-temperature superconductors, next-generation rechargeable batteries, and biofuel catalysts, Rare earth elements are crucial.

Rare Earth is not really ‘rare’; for instance, thulium is 125 times more common, and cerium is whooping 15,000 times more abundant than gold. However, unlike gold or other minerals, they are mostly “dispersed,” in relatively low concentrations, making it harder to mine economically.

Heavenly solution

When earth does not provide enough, it is human to look up to the heavens. Helium-3, an isotope that could fuel future fusion reactors, is extremely scarce on earth. Called ‘lunar gold’, the moon has an estimated 1,100,000 metric tonnes of helium-3 down to a depth of a few metres.

Furthermore, the rocks in the Procellarum KREEP Terrane region of the moon are rich in “KREEP” –potassium (K), rare earth elements (REE), and phosphorous (P). While C-type asteroids are abundant in water-converted rocket fuel, the S-type asteroids are rich in nickel, cobalt, gold, platinum, and rhodium.

If only we could mine and bring the minerals from the moon, if only we could tug a small asteroid near earth.

The audacious NewSpace business plan is to develop, build and send robotic crafts to space to scout asteroids for precious metals and set up 3D printed mines to bring resources back to Earth.

The Asteroid Miner’s Guide to the Galaxy says: First, a fleet of satellites will be dispatched to outer space, fitted with probes that can measure the quality and quantity of water and minerals in nearby asteroids and space rocks. Armed with that information, mining companies like DSI will send out mining space robots to mechanically remove and refine the material extracted. Some semi-processed materials would be returned to earth whereas in some cases, they will be processed in space itself. For instance, extracted water would be processed into space fuel, stored in the space station and serve the outbound space crafts like a gas station in space.

Sci-fi to reality

Are we dealing in hypotheticals? No. Not really. Surely this will not be realized the day after but it is in the realm of reality around the corner.

The returning astronauts of the Apollo mission brought a pocketful of moon rocks. Although the Soviets abandoned human-crewed moon missions, they successfully executed three robotic sample return missions. The last of these, Luna 24, returned with samples from Mare Crisium, located in the Moon’s Crisium basin, from as deep as two meters below the surface on August 22, 1976.

Recently China’s Change 5 lunar sample return mission safely returned on December 16, 2020, with 2 kilograms of lunar soil. After a torturous six-year journey, Japan’s Hayabusa2 returned with 5.4 grams of sample from an asteroid named Ryugu on December 6, 2020.

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission, which launched in September 2016, arrived on Bennu asteroid in December 2018, collected 60g of sample, and is on its return journey and is expected to land on September 24, 2023. India, Japan, and Russia plan to launch lunar robotic missions in the coming years as well.

As of July 19, 2021, nearly 26,238 Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs) have come close to the earth. Of these, about 6,417 are less than 30 meters in diameter. Shifting through this catalogue, a team of researchers have identified 12 candidates that we could reach out and capture using existing rocket technology.

Called Easily Retrievable Objects or EROs, these asteroids are 2–60 meters in diameter. They show that even with current technology, one can tow a 4-metre-wide space rock named 2006 RH120 to the Lagrange point. At these Lagrange points, the gravitational pull of Earth and the Moon are equal, making the object stay put, making it easy to mine.

Commercialisation of space

The marketization of space, albeit to a limited extent, took place almost from the beginning. In the Cold War context, the man in space and mission to the moon were played as part of the national ego.

The satellite sector, particularly the communication and remote sensing satellites, was commercialized early on. Intelsat, an intergovernmental agency, launched and commercialized the communication satellite network worldwide.

There are no words to describe the feeling. This is space travel. This is a dream turned reality https://t.co/Wyzj0nOBgX @VirginGalactic #Unity22 pic.twitter.com/moDvnFfXri

— Richard Branson (@richardbranson) July 12, 2021

Way back in the 1970s, Hermann Bondi, the head of the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO), wrote,“It is clear…that there must be three partners in space, universities and research institutions on the one hand, the government on the second and industry on the third.”

Boeing and other companies have also manufactured many components and systems used in NASA missions. By the 1990s, it was not uncommon for the Soyuz rocket to sport logos of the Tokyo Broadcasting System (TBS) and other corporate sponsors. The symbol for Pizza Hut was painted on the Russian rocket and commercials filmed at the space station.

What marks the birth of SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, Blue One, MoonEx and other NewSpace is not the commercialization of space technologies or ‘democratization of space travel’ by offering rides to those who can pay their way to space. They are but just the tip of the iceberg. What these symbolize is the ‘privatization’ of outer space.

Soviet moon

Do we have launch vehicles that can take us to asteroids? Yes. Have we landed on asteroids? Yes. Have we been able to collect soil and rock samples from asteroids? Yes. Have we brought back samples from celestial objects? Yes. So what stops us from sending a fleet of spacecraft to mine and bring back the riches? One word: Soviet Union.

The world woke up to a surprising news on February 4, 1996. Luna 9, the Soviet robotic lander, had successfully touched down on February 3, at 21:45:30 Moscow Time (February 4, 00:00:30 IST) on the eastern edge of the Ocean of Storms (Oceanus Procellarum), a vast lunar mare on the western edge. The petal-like outer shell of the craft opened, and mini Soviet flags and pendants were ejected all around. In 1959, the Luna 2, carrying several medallions with the national coat of arms, had impacted the moon.

By then, the Soviets had beaten the USA in launching the first spacecraft, the first animal in space, placing the first human being in orbit, photographing the never-before-seen far side of the moon with Luna 3, reaching Venus, the first woman in space and undertook the first spacewalk. The Americans were trailing in the “space race”, struggling with repeated failures of its Pioneer and Ranger missions to the moon with Surveyor 1 landing on the moon only in May 1966. It appeared that the first human to set foot on the moon would be a Soviet.

Based on historical precedents of exploration and conquest, no extant principle of international law would have prevented the Soviet Union from claiming the moon or a large part of it. With the Luna 9 landing, the western media went into a hyperdrive. Newspapers speculated that the Soviets were waiting for human landing to stake the claim. Many Western nations were worried that the Soviets could seize the ‘ultimate high ground.’

Province of mankind

The US was mired in the impossible Vietnam war. A cash strapped and worried Lyndon Johnson, the President of the United States, wanted to negotiate and prevent Soviet territorial claims.

Nonetheless, way back in 1962, Soviet Union had submitted to the UN a resolution that “Outer space and celestial bodies are free for exploration and use by all States; no State may claim sovereignty over outer space and celestial bodies”.

Arthur J Goldberg, Permanent Representative of the United States to the UN, enticed the Soviets to enter a treaty. After six months of intense negotiations, after the US agreed to sign the limited test ban treaty, the USSR settled. The UN General Assembly gave its approval to the Treaty on December 19, 1966.

As of February 2021, 111 countries are party to the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, or in short, ‘Outer space treaty 1967’. 23 other countries have signed the Treaty but have not completed ratification.

Shaped by the socialist vision of the USSR, the Treaty is laced with a proto-communist idea. It declared that “outer space…is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means” and “exploration and use of… shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries and shall be the province of all mankind”.

It further stated that “astronauts shall be regarded as the envoys of mankind” and that the “states shall be responsible for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities”. It also stated that the “activities of the non-governmental entities… shall require authorization and continuing supervision by appropriate state party to the treaty”.

While the Treaty does not prevent nations from extracting resources from celestial bodies, it unequivocally states that these activities shall benefit all of earth’s inhabitants.

New wild west

The lure of virgin lands in the American west drove American settlers into native communal lands. In 1862, the US Congress passed the Homestead Act that opened up the American West to settlement. These areas were the traditional or Treaty lands of many American Indian tribes. Lands hitherto held as communal property by native tribes were violently wrested and given predominately white settlers.

Akin to the Homestead Act of 1862, the US congress voted for the ‘Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act’ in 2015. Signed into law by President Barack Obama on November 25, 2015, this law allows US citizens and industries to “engage in the commercial exploration and exploitation of space resources”, including water and minerals.

The Act states that “the United States does not … assert sovereignty, or sovereign or exclusive rights or jurisdiction over, or the ownership of, any celestial body”. However, prodded by NewSpace businesses such as Planetary Resources, Inc., Deep Space Industries and Bigelow Resources, this unilateral law permits a US citizen to “engaged in commercial recovery of an asteroid resource or a space resource… possess, own, transport, use, and sell the asteroid resource or space resource…”

In what appears to be the classic rendition of the “he who dares wins” philosophy of the Wild West, this Act allows the private sector to make space innovations without regulatory oversight during the first eight years and protect spaceflight participants from financial ruin.

Alarm bells

Perhaps the Space Act 2015 is the beginning of the end of the Outer Space Treaty that stood the test of times. As space becomes a probable site of profitable ventures, perhaps the Treaty’s proto-communism must falter and fade away.

What happens in the realm of cosmic might have an impact on the Terra Firma too. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) drew on the sentiments of the Outer Space Treaty to place the ‘seabed and ocean floor beyond a nation’s territorial waters as a common heritage of mankind’. International law says that exploration and exploitation must benefit mankind as a whole.

The International Seabed Authority was established to oversee the 1982 convention to allocate regions to countries for exploitation. Still, in principle, any profits arising from, e.g., the mining of polymetallic nodules, are to be shared with all humankind, including ‘developing States, particularly the least developed and the land-locked among them’.

In tandem with the increased technological feasibility of exploiting resources and accumulating profits, spatial justice in the outer and high seas might be denied to the weak and small.

Disaster in making

The environmental implications of NewSpace might seem ludicrously far-fetched. Take the case of the low earth orbit. Sky and Space Global (SAS), a new age business, proposes to launch a constellation of 200 shoebox-sized nanosatellites in equatorial Low Earth, each weighing just 10kg. To be air-launched in batches of 24 by Virgin Orbit, these trains of satellites would appear overhead one after another. The procession of satellites would act like a mobile tower providing digital access to any place on Earth.

Similarly, Elon Musk is planning for a vast 4,400-satellite constellation offering uninterrupted fast global internet coverage. OneWeb is looking to place an 800-satellite constellation, and Google and Samsung are mulling similar options.

Already the near-Earth orbit is so chaotic that a big disaster is waiting to happen. Recently SpaceX’s new Starlink satellites were almost colliding with a European Space Agency satellite (ESA). The catastrophe was averted at the last moment when the ESA satellite fired its rockets and move from the path.

Satellites have limited fuel to maintain their station in space. No one would like to waste it. With no international regulation to compel a satellite to move out of a collision path, space jam is the lawless wild west. With so much debris crowding the low earth orbit, a satellite can be wrecked by a random piece of junk with no trace of its origin. The free market is hardly able to self-regulate.

Wild west needs to be tamed

The outer space might seem limitless; so did our earth a few decades ago. Who would have imagined in the 1850s that the pollution from the industries would turn into an ecological disaster?

The space sector is not just enabling Netflix and entertainment. Satellites in space monitor weather, help in climate change studies and assist search and rescue operations. The social good outweighs it. Scarce resources must be used wisely and justly.

The water on the moon might be enticing with possibility. Still, the supply of ice on the moon is limited—just about three to five cubic kilometres. The water ice on the poles is just over 600 billion kilograms, just enough to fill about 240,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools. In no time, unbridled exploitation could chew away all the water and leave the moon barren.

The old witticism that the only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history finds a sorry parallel here. The glitter from outer space spectacle should not blind us to the fundamentals that shaped the outer space treaty. People before profit.