- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Soothsayers see an uncertain future with saffron surge

At 10 pm, men dressed in black coats and saffron dhotis, with saffron turbans resting on their heads, walk into a village burial ground. Carrying cloth sacks filled with their bread and butter — cowrie shells, a mat, damaru, picture of their deity — they pray there till midnight, before walking the streets of the village telling fortunes. They stand in front of each house, rolling the...

At 10 pm, men dressed in black coats and saffron dhotis, with saffron turbans resting on their heads, walk into a village burial ground. Carrying cloth sacks filled with their bread and butter — cowrie shells, a mat, damaru, picture of their deity — they pray there till midnight, before walking the streets of the village telling fortunes.

They stand in front of each house, rolling the damaru to announce their arrival, and predict the future of the residents, who listen sleepily. The next day, the soothsayers take off the black coats and visit the houses again to ask if the occupants heard their fortunes. If a family has any questions about the predictions and is satisfied with the sayings, it gives the soothsayer some money, food or clothes. The soothsayers roam from village to village doing this.

This is how about 500 Kattu Naicker families in Satyamurti Nagar village in Madurai district eke out a living ever since they migrated from the Nilgiris generations ago.

Origin story

In 1954, a group of soothsayers from the Kattu Naicker community surrounded the then chief minister Kamaraj on the roads of Madurai, demanding a permanent residence in the area. The chief minister was hesitant to give them the land at first as they were known as wanderers. But the community convinced him that they would settle on this land.

Acceding to their demand, Kamaraj gave ‘patta’ land to a few people and named it after the Congress leader Sundara Sastri Satyamurti. However, villagers believe Satyamurti Nagar was named after their ancestor who won them the land.

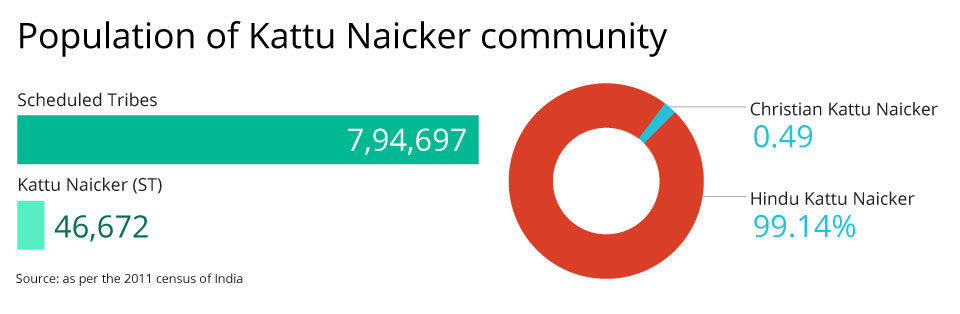

From a small group of soothsayers, the village’s population has now swelled to about 500 families. At one point, it was a Hindu-dominated Scheduled Tribe village. But a few conversions to Christianity to escape the caste system brought religious diversity to the village.

The first person who converted to Christianity from the village did so in 1982. Talking about why he converted, Paul Murugesan says, “After the death of my father and mother in 1980, no one was there to take care of me. I was 19 years old at the time and I had to eke out a living by doing odd jobs. Since I belonged to the Kattu Naicker community, I was not given any decent job, even though I had completed my high school.” He went to Madurai where he met Christian missionaries and spent time with them.

He returned to the village in 1988 in order to get rid of his people’s caste identity. That’s when several people opted to join Christianity. Paul is a pastor in the village now.

Though some sought refuge in the arms of a different religion, the village of Satyamurti Nagar was never divided along religious lines. Everyone continued the same practices as before.

“Since we are all relatives and we knew that our origins were the same, we never minded the religious differences. All marriages, including inter-religious ones, were conducted in our traditional way and Hindu people used to visit churches here,” Paul says.

United in the past

This unity is a thing of the past now, as the converted Christians face discrimination at the hands of the Hindu Kattu Naicker community.

During a village panchayat meeting held a couple of months ago, the village leader issued an oral order telling people of the Hindu community to stay away from the Christians and to not have any sort of communication with them.

When The Federal visited the village, there were posters pasted on the temple and the community hall stating that religious conversions are strictly restricted in the village. This reporter interacted with both the Christian and Kattu Naickers, and found that discrimination is rampant in the village.

According to the villagers, the Christians are not supposed to enter the main streets of the village and should not be given drinking water by any Hindu. If anyone violates the village sarpanch’s oral order issued a couple of months ago to refrain from talking to the Christians, they will have to pay a fine of ₹5,000.

M Alexander and M Eshwari, a young couple that married around three months ago, are not allowed to talk to their parents, who are now Hindu Kattu Naickers.

Talking about the discrimination they face, Alexander says, “I am a Christian and Eshwari is a Hindu, and we married in our traditional way. Our families used to talk to each other, we had a good relationship. But, in the last one month, after the gag order by the village sarpanch, my parents have returned to Hinduism.”

Unlike his parents, Alexander is reluctant to convert to Hinduism. “I know the consequences. If I return to the community, either I have to apply for a government job through ST quota or I have to become a soothsayer, following in my father’s footsteps. So, I have not return,” he adds.

Eshwari says that her family is not talking to her, fearing that villagers will send them out of the village or issue a fine of ₹5,000. “I live on the edge of the village, and I couldn’t refrain from visiting my parents, who live in the main area. But after I would go over to their house, the village seniors would surround the house, humiliate and abuse them for talking to a ‘Christian’ woman. They threatened to fine my parents as well,” she adds.

So, Eshwari has stopped visiting her parents and talks to them over the phone after dusk.

Even elderly people who had turned to Christianity have been left alone as they are not ready to go back to Hinduism.

P Victor Subbaiah, who converted to Christianity along with his family around a decade ago, is now left outside a prayer hall in the village, after his family returned to Hinduism.

“After the villagers issued the gag order, my children went back to Hinduism and only my sister, Kaliyammal, used to take care of me. But, after the villagers threatened her saying that she would be denied her basic rights, including grocery items and water in the village, she also left me,” Victor says woefully.

The Christians in Satyamurti Nagar are completely clueless as to why they are being treated this way all of a sudden. They can’t help but wonder what went wrong.

Hindu radicalisation

According to villagers from another caste, who are settled in the village, it all started after Hindu Munnani, a Hindu outfit that strongly opposes Christian conversions, gained grounds in the village.

Talking about the emergence of the Hindu Munnani in the village, a shopkeeper says on condition of anonymity that it all started on one Ganesh Chaturthi day. “The villagers never had the tradition of celebrating Vinayaka Chathurthi. But, in 2017, Hindu Munnani entered the village and issued pamphlets saying that it is keeping a Vinayaka statue in a neighbouring village,” the shopkeeper explains.

A week later, its members visited the village again and said they wanted to keep a statue there as well. “Though the village sarpanch and village seniors were initially reluctant, after several talks, they agreed to keep the idol here and it all started,” he adds.

Thereafter, Hindu Munnani members started conducting street meetings and hurling abuses at the Christians and Muslims. “They also leveled baseless allegations against the churches in the village during meetings held in January, March, June, September and November of 2018,” the shopkeeper says.

Even then, there had been no discrimination between the Hindu Kattu Naicker and the Christians.

According to a village senior, it all erupted after police arrested two men from the Kattu Naicker community on charges of Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act.

According to people in the Kattu Naicker community, they have a unique system of marriage that does not involve either a mangal sutra or a ring. “If a man wants to marry a woman, he should take her and sleep with her for a night. The next morning, the couple should inform their parents. After that, the parents and relatives take them to a temple, where tulsi water is sprinkled on them three times, and the marriage is done,” explains M Mayandi, a senior soothsayer.

According to Mayandi, even though they are separated by two religions, marriage rituals have been conducted in their traditional style for years. But, recently, two young couples married in the traditional way and the girls were minors.

The two boys who married the minors were arrested by the police. The two girls were sent home. Ashamed that his sister was sexually active, a brother of one of the girls jumped in front of a train and died by suicide, says Mayandi. It hurt our traditions and cultural sentiments. “We strongly believe the Christians are behind this, since they are now grown and educated,” adds Mayandi. After this incident, Mayandi stopped his family from going to churches.

According to a senior soothsayer who did not want to be named, the campaign of the Hindu Munnani, after the arrest of the two boys and suicide of the youth, turned violent.

“They accused the Christians of owning crores of money by filing complaints against the Kattu Naicker in the village. The narrative of the Hindu Munnani men sat well with the community and now our community is against the Christians,” says the senior soothsayer, whose children have converted to Christianity.

When asked about the marriage practices, pastor Peter Krishnan, who was originally from the Kattu Naicker community, says that it was quite common in the community. “Even I married at the age of 17 and my wife was just 14. We do not have any intention of stopping such marriages. We still respect and follow our traditional marriage practice,” Peter says.

When asked about the discrimination, a soothsayer and Hindu Munnani worker, K Kaliappan, says that they don’t want Christians in the village. “Tamil Nadu itself is a Hindu state. Why should we allow Christians into our village?” he asks.

“We have the support of the RSS and we have the strength to bring more Hindu Munnani cadres into the village to support our cause. We will not rest until we chase the Christians out of the village,” says a Hindu Munnani worker

“We have the support of the RSS and we have the strength to bring more Hindu Munnani cadres into the village to support our cause. We will not rest until we chase the Christians out of the village,” he says.

Village sarpanch R Alagar Pandi, who is also a Hindu Munnani cadre now, says that he can’t tolerate Christians who spoil their culture. “We are not against all Christians. We are only against the Christians who spoil our culture. We want all the Christians to come back to their mother religion.”

- Meenakshipuram is a village in Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu where over 1,000 people were believed to have converted to Islam from Hinduism citing discriminatory practices in the village in 1981. This not only got the attention of the Tamil Nadu government but the Centre as well.

- BJP leaders including Atal Bihari Vajpayee visited the village and asked the villagers to return to Hinduism. However, it did not work out. A year after, a few people supposedly returned to Hinduism.

- As a result of the mass conversions, the State government set up an inquiry commission and based on its revelations, former chief minister J Jayalalithaa passed an anti-conversion bill in the Assembly. It was not a blanket ban on conversion but to prevent forced conversion.