- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Shramik Specials: Train to hell and back

A common refrain of migrant workers from across the country is that boarding the special Shramik train has become akin to winning a lottery.

At the Thiruvananthapuram Central station, Gopal Mandal, 33, runs out of patience as he awaits to board the Shramik Special train to West Bengal. Around 8 pm on May 26, as the train approaches the platform, Mandal cranes his neck to get a better look, his face mask soaked with sweat, slips below his nose. Once seated inside the train, the series of events that unfolded in the past two...

At the Thiruvananthapuram Central station, Gopal Mandal, 33, runs out of patience as he awaits to board the Shramik Special train to West Bengal. Around 8 pm on May 26, as the train approaches the platform, Mandal cranes his neck to get a better look, his face mask soaked with sweat, slips below his nose. Once seated inside the train, the series of events that unfolded in the past two months flash in front of Mandal’s eyes.

Following the countrywide lockdown announced in March, Mandal, a mason, found himself stuck with nine others from Bengal for more than two months at government camps in Thiruvananthapuram, looking for ways to return home. But nothing worked in their favour until May 26 — the day of their departure that followed a series of unimaginable chaotic events.

Similar, if not more, harrowing tales of wait emerged from across states, as migrant workers, left jobless and hungry by the lockdown, struggled to return home, before finally boarding a train home where more pain and hunger awaited them.

The chaos

From booking tickets to delayed departures, congestion, no food or water onboard to unexpected stops and detours, Shramik Special journeys for thousands of migrant workers returning home from across cities proved to be a harrowing experience of torture and mistreatment by a government with no plans and compassion.

The Indian Railways claimed to have run 3,274 “Shramik Special” trains till May 25 across the country and transported more than 44 lakh passengers to their home states.

But the big numbers fail to conceal the bigger mess unleashed on the railway tracks, triggering blame games between the Centre and non-BJP states even as stranded workers scamper for information on train schedules.

A common refrain of migrant workers from across the country is that boarding the special train has become akin to winning a lottery. Until the last moment, the stranded workers do not have any inkling about their impending journey.

They are huddled to stations only hours before the scheduled departure of trains. Neither those who are still stranded in camps nor the ones who have been fortunate enough to get the elusive second-class berth at a ‘premium price’ are able to figure out the criteria being followed in preparing the passengers’ list.

For instance, Mandal and his friends initially failed to book their train tickets even after trying every possible means. “A friend had called us on May 21 from our village in Sunderbans to inform us that cyclone Amphan had wrecked our houses and agriculture fields back home. He read out a list of trains the state government had arranged from various destinations to take back its stranded citizens,” Mandal says.

But their frantic attempts to book tickets online did not yield results. They then tried to reach the railway station to buy the tickets. But police stopped them from venturing out of their makeshift camp at a government school in Poojappura, Thiruvananthapuram.

“For five days we tried everything possible. We approached the local police station in Thiruvananthapuram and also officials back home in Gosaba in Sunderbans. A local guard at the school gave us a phone number of an NGO, we sought their help too,” says Mandal.

By May 26, they gave up all hope of boarding the train until a journalist of The Federal in Thiruvananthapuram took up their case with the “right authorities”. Following that, the migrant workers finally managed to board another train leaving for Bengal that very night, thus fast-tracking their journey by two days.

Mandal is furious that he had no inkling about the second train. “In the list, we found a train that was scheduled to leave for Malda (West Bengal) from Thiruvananthapuram on May 28. We were not at all aware of this train on May 26.”

Railway officials, however, are tight-lipped about the utter confusion. A senior Eastern Railways official, who doesn’t want to be named, says the responsibility of boarding passengers to the train entirely lies on sending state governments.

It is the sending states which prepare the list of passengers from their database of migrant labourers and bring them to designated railway stations, he says.

“Running trains between two states is a decision that the political class has to take. After they decide, we get a request and accordingly the trains are deployed,” says Ashok Kumar Verma, divisional railway manager (DRM), Bengaluru, almost echoing the version of his colleague from the Eastern Railways.

The non-BJP state governments, however, refute the Railways’ claim.

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee told a group of reporters that 36 trains were being sent to the state from Maharashtra by the Railways without taking consent of either the sending or the receiving state.

“After hearing about the movement of these trains, we got in touch with the Maharashtra government. But even it was unaware of the train schedules. The Railways has unilaterally taken the decision to run the trains,” she alleges.

Earlier, Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, too, made similar charges against the Railways for sending trains ‘without notice’.

The Ministry of Railways, in a press release recently, announced starting operations of 200 passenger trains from June 1, apart from the Shramik trains. Bookings for all these trains began from May 21. Passengers who want to book tickets can only do so from the IRCTC website or the mobile app. Reservation centres are shut across the country, the press release said.

However, just like Mandal and his friends, many others found it impossible to book tickets online even earlier when IRCTC had announced opening the online booking services on May 11 at 4 pm. Amit Kumar Dash, 25, was one of them.

As thousands of prospective travellers logged in to the website at once, the server crashed. As a result, the process that was supposed to begin at 4 pm, was delayed by two hours.

However, when the website went down for two hours, the Railway Ministry announced that “data pertaining to special trains was being fed in the IRCTC website”.

Amit logged in to the IRCTC website again on May 12, only to find that tickets were selling in a matter of seconds. “Surprisingly, getting a confirmed train ticket in this situation just depends on one’s luck, and not on availability of seats. The IRCTC website crashed several times and I had to struggle with the booking process for two-three hours.”

He finally got a confirmed ticket for May 18 in an AC-1 Rajdhani Express train (Mumbai to Delhi).

But even after boarding the train with a confirmed ticket in hand, there is no guarantee of reaching the destination without unprecedented delays and unusual detours.

For example, a Shramik Special train from Mumbai to Gorakhpur ended up in Odisha. The Railways’ explained the diversions as “route rationalisation” to navigate “network congestion”. The Indian Express cited a senior Railway official as saying that the detours were taken “so that trains are not held up at one place for hours without water and food”.

It also blamed the weather. “There’s no way a train can reach a different destination. At times in conditions like a cyclone or congestion in the route, we divert some trains to go on a different route. But they will reach their destinations,” Verma says.

The reasoning for the route diversions follows similar explanations over ticket prices earlier.

Who’s paying, how much and why

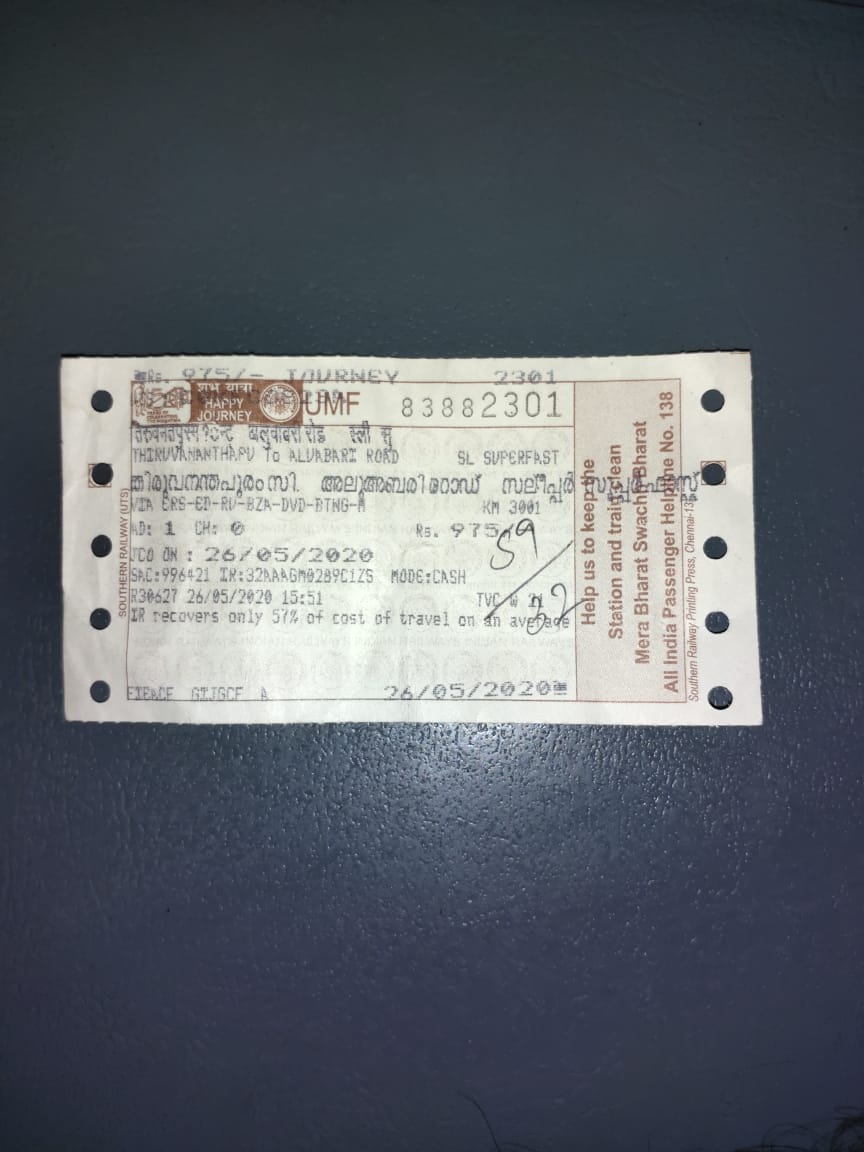

There is also no clarity on ticket prices. According to Mandal, he had to pay ₹810 in February to travel to Thiruvananthapuram from Howrah in West Bengal. This time, the price written on the ticket was ₹975.

Luckily, Mandal and other passengers from Bengal did not have to pay the fare as the West Bengal government is bearing the expense.

Many other states such as Chhattisgarh are also paying for the tickets of their homecoming citizens.

However, not everyone has been as lucky. Sunny Singh, one of the early birds to catch the Shramik Express from Bengaluru to Danapur in Bihar on May 5, had to pay ₹930 and “some more”.

“We were asked to pay ₹930. They did not even return the balance ₹70 when I gave them ₹1,000,” he tells The Federal.

The Railways have claimed that the ticket price includes the charge of meals served on the train. It claims to have distributed more than 74 lakh free meals and more than 1 crore water bottles to travelling migrants. However, numerous videos and personal accounts that have emerged in the past few days paint a different picture.

Food and water

There are a lot of complaints about food distribution to the onboard passengers. “We were only served with two proper meals, once when we boarded and one more next morning. That was it throughout the 38-hour journey,” says Sunny Singh.

Mandal’s experience was a tad bit better.

Before boarding the train at Thiruvananthapuram on the evening of May 26, the Kerala government handed over a dinner packet to each passenger containing chapattis and vegetable curry and a bottle of mineral water.

The next morning around 9.30 am at one station, which Mandal could not identify, 72 breakfast packets and an equal number of mineral water bottles were left near the door of the coach.

“There was no railway staff in the bogie to distribute the packets. Naturally, chaos ensued as passengers competed with each other to get the packets. Though there was one packet each for every passenger, many did not get anything while some got away with two,” he says.

Similar scenes were repeated during lunch and dinner time. Dinner packets of vegetable biryani were served around 9.30 pm on May 27. The following day (May 28) the passengers got their breakfast of cake, biscuits and noodle packet at Kharagpur only around 1 pm.

The passengers could not buy anything even on the stations where the trains stopped on the way as no kiosk was open. “The stations were empty except for a handful of police personnel and railway staff.” At some stations, even the water taps were running dry.

Similar complaints of inadequate supplies of food and drinking water, apart from clogged toilets with no water, during their journeys came from a number of passengers travelling on various routes.

The Indian Railways during normal times before the lockdown ran 13,452 passenger trains, transporting 23 million passengers every day. But now, it has failed to run a few hundred trains daily without long delays, forcing passengers to go without food and water. Some even had to face attacks from people on platforms trying to barge into special trains.

As many as 1,300 people travelling by a special train from Haryana to Nagaland, came under attack from scores of people waiting at Danapur in Bihar. When the train halted at Danapur, an anxious crowd at the platform, desperate to reach their own homes, tried to barge into it. When the passengers inside tried to stop them, it led to an argument and an attack on the train. Many passengers were surprised to see such a huge crowd allowed to gather at the platform in complete violation of social distancing guidelines.

Not that the social distancing protocol inside the trains are any better. The Centre on May 12 announced to run Shramik specials with full capacity, withdrawing its earlier norm of keeping the middle berth vacant in order to maintain social distancing.

Where is social distancing?

Mandal got to experience it during his journey. “All the eight seats in each compartment are occupied. There is no mandatory one metre distance between two passengers. Moreover, every time food packets come, there is a mad rush to get them. No railway staff was on board to oversee the food distribution.”

Fortunately, toilets were cleaned twice in the entire journey, he adds.

Already, various states are witnessing a spike in Covid-19 cases with many migrant workers returning home testing positive for coronavirus.

In Bengal, the overall rate of detection of positive cases among those tested is 2.6%, while in case of migrant labourers it’s 10%.

Chief Minister Banerjee blames the lack of cooperation from the Railways in scheduling the trains for the surge in positive cases.

However, much remains to be said about the state’s own preparedness too.

The passengers after deboarding trains are ferried to their respective blocks in jam-packed buses without caring for social distancing protocols.

Amit Dash narrates a similar experience on his arrival at the New Delhi station. “When I deboarded the train, there was no RPF official on the platform to manage the crowd or divert them towards the exit gate. The coolies rushed towards passengers for ferrying their luggage outside the station, just like on usual days.”

The only visible change at railway stations right now is the mandatory thermal screening of passengers, he adds.

However, a Northern Railways official denied this. “Passengers deboarding trains are made to follow social distancing norms at the platforms and diverted accordingly to the exit gate of the station. Once outside, they are then directed to a team comprising officials of the district magistrate,” says the official who wishes to remain unnamed.

No one to listen

The same Northern Railways official tells The Federal that the feedback and grievance redressal mechanism of the Railway Ministry can only receive complaints/suggestions from passengers travelling in the special passenger trains (which began from May 12) and not Shramik Specials since these trains are not registered on the NTES (National Train Enquiry System). In case anyone wants to file a complaint related to Shramik Specials, they can do so on the IRCTC app.

(To put things in perspective, the Indian Railways on May 14 had cancelled all passenger trains till June 30 and said only Shramik Special trains and Special Rajdhani Express trains will continue to ferry stranded people.)

“It will also receive suggestions/complaints and respond to them from those travelling in the special passenger trains starting from June 1,” the official adds.

The operations of the Shramik Special trains are mostly under the control of the railway zones. The official explained that the railway divisions are responsible for the maintenance of the trains.

While stories of the Indian Railways’ mismanagement continued to emerge and rip open the covers off the Centre’s lack of plan for the biggest human migration India has seen in decades, Union Minister for Railways Piyush Goyal hasn’t addressed or acknowledged the crisis directly.

He, however, passed the buck to the states, especially non-BJP ruled governments — West Bengal, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Rajasthan (Congress) and blamed them for ‘defaming’ the Centre’s efforts.

As of Thursday, nine people had died on the Shramik trains in 48 hours. But what perhaps shocked and shamed Indians most was a heartbreaking video of a toddler trying to wake up his dead mother lying on the platform at a railway station in Bihar. Initial reports and social media posts suggested that the mother died of hunger and thirst after being on a train for four days. The Indian Railways, however, said she died of pre-existing ailments. A PTI report quoted the deputy SP of the Government Railway Police in Muzaffarpur as saying that the woman “was also mentally unstable”. The report, however, didn’t cite any evidence to confirm her mental state and how it could be connected to her death.

However, not every journey ended on such a grim note. Mandal, after nearly 46 hours of a train journey, finally reached Dankuni near Kolkata. But home is still a long way away. A mandatory quarantine means holding on to his train of patience for 14 more days.

(With inputs from Nikita Prasad, Samir K Purkayastha, Prabhu Mallikarjunan, Sanghamitra Baruah)