- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

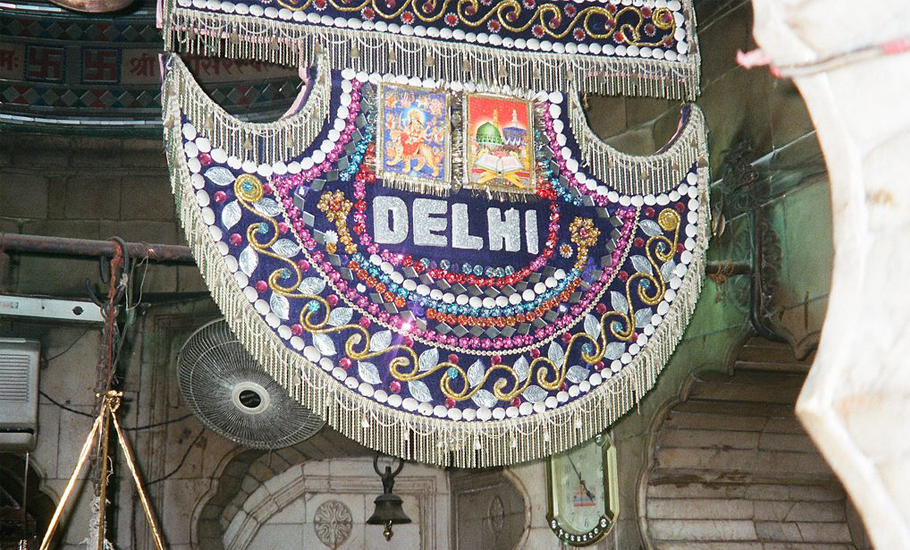

Saying it with flowers: Delhi’s Phool Walon Ki Sair needs to find its feet again

Just when a hot and humid Delhi would begin giving way to a cool respite signaling that winter was on its way, the city of many seasons, would enter a unique syncretic festival underlining that it was also a city of many faiths, many religious hues and also many flowers. For over two centuries, the arrival of autumn in Delhi was also the time for the city to celebrate Hindu-Muslim unity...

Just when a hot and humid Delhi would begin giving way to a cool respite signaling that winter was on its way, the city of many seasons, would enter a unique syncretic festival underlining that it was also a city of many faiths, many religious hues and also many flowers.

For over two centuries, the arrival of autumn in Delhi was also the time for the city to celebrate Hindu-Muslim unity subtly through a ‘rosy walk’—Phool Walon Ki Sair. The walk was interrupted in 2020 when the Covid pandemic changed life as we knew it. For Delhi, however, the loss has been more pronounced. While there has been an attempt to resume all that halted in 2020 through improvisations and adjustments, the Phool Walon Ki Sair seems to have been conveniently relegated to oblivion with no concerted efforts to revive it.

On a day, tableaux from various states of India moved down Rajpath, the fact that Phool Walon Ki Sair, which traditionally sees the participation of floral chhatris from several Indian states, has been missing became even more pronounced.

Ironically, even as opposition-ruled states—West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Kerala—sparred with the Centre over the exclusion of their Republic Day tableaux in the run up to the parade in Delhi, the Phool Walon Ki Sair has been missing without any demand from any quarter for its resumption.

The significance

Phool Walon Ki Sair is a festival that was started way back in 1812 by Mughal emperor Akbar Shah II and his queen Begum Mumtaz Mahal. As part of the annual festival, people of Delhi from across communities participated in a procession led by the royal family.

Taking off from the tomb of Nizamuddin Auliya, the seven-day annual procession meandered through the city to reach Mehrauli before culminating in the offering of a chadar of flowers at the dargah of Sufi saint Khwaja Bakht. What made the festival truly secular was that the emperor offered a floral chhatri at the ancient Yogmaya temple close by.

Phool Walon Ki Sair both literally and figuratively stands for a floral, or rather a florists’ stroll, even as it actually—among other things—signifies a long haul of a mostly painful and troubled history that Delhi braved till destiny could see it through. The festival commemorates this aspect of Delhi with a colorful carnival.

Much like Delhi, which has endured many invasions and plunderers, Phool Walon Ki Sair too has had its share of existential struggles.

In 1942, during the Quit India Movement, the British stopped the celebration in a bid to further divide Hindus and Muslims. Despite the spanner thrown by Muslim League in the struggle for freedom in the 1940s, Phool Walon Ki Sair continued to symbolise India’s composite culture nurtured down the ages through the vast swaths of Indo-Gangetic basin.

The festival, however, remained suspended till 1961when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to revive it. Nehru not only revived the festival but also ensured that it was observed with the same fervor that was witnessed during its observance prior to Independence.

Nehru entrusted Yogeshwar Dayal, a businessman, landlord and art connoisseur from Chandni Chowk, with the responsibility to organise the festival. Dayal set up the Anjuman-Sair-e-Gul Faroshan, a registered society, in 1961. When Yogeshwar Dayal passed away in 2006 his daughter Usha Kumar was tasked with taking the mantle ahead.

While the festival was organised in Delhi, floral chhatris came in from various states to symbolise participation and larger unity.

After Nehru, his daughter, late Indira Gandhi, ensured more floral chhatirs from other states were added as a mark of respect to Yogmaya Devi and to lend more colour to the pageant that goes up to the tomb of the Khwaja.

Today, Anjuman-Sair-e-Gul Faroshan organises the annual fest with support and collaboration of the Delhi government.

How the festival came into being

The origin of Phool Waalon Ki Sair dates back to the early nineteenth century, the reign of the Mughal King Akbar Shah II (1808 -1837). The emperor was quite unhappy with his eldest son Sirajuddin or Bahadur Shah Zafar and wanted to nominate his younger son Mirza Jahangir as the successor to the throne by declaring him Wali-Ahad (crown prince).

Then British resident at the Red Fort, Sir Archibald Seton, did not approve of the move. Historians say Seton’s dislike for 19-year-old Mirza Jahangir stemmed from the fact that the latter had once insulted Seton in open court. Jahangir is said to have gone to the extent of firing a shot at the resident. While Seton managed to dodge the bullet, his orderly was killed in the incident.

A livid Seton exiled Mirza Jahangir to far off Allahabad. Queen and Jahangir’s mother Mumtaz Mahal Begum was devastated by the news and took a vow that if her son came back from Allahabad, she would offer a floral wreath and linen chadar at the revered Mehrauli shrine.

A few years later, Mumtaz Mahal’s wish came true and Jahangir was released. Keeping her vow, Mumtaz Mahal went to Mehrauli. It is said that the imperial court also shifted with her to Mehrauli and so did a section of people from the Walled City.

Soon, the emperor ordered that tributes in the form of a floral pankha (fan) be offered at the equally revered Yogmaya Mandir which stood in the vicinity of the shrine. Encouraged by the enthusiastic response generated by this gesture among the people, the emperor decided to hold this new festive ritual every year after monsoon rain stopped. Legend has it that this is how offering pankha and chadar at the temple and shrine respectively came to be a tradition.

The scale and importance the emperor attached to the festival can be assessed from the fact that the Mughal court was also shifted to Mehrauli for the seven days during which the festival was observed every year.

The yearly show that had the royal patronage attained even greater glory during the reign of Bahadur Shah Zafar who succeeded Akbar Shah in 1837. The emperor went on to celebrate Phool Waalon Ki Sair until 1857 when Delhi came under siege of the British troops and his rule came to an abrupt end.

Celebrations en route

During the Mughal era, the people of Delhi used to walk with flowers from Chandni Chowk to Mehrauli, a distance of about 32 km. The path had several wayside lodges that offered rest. These were Arab Ki Sarai, Qutub Ki Sarai, Parsi Temple Ki Sarai, Yogi Ki Sarai, Sheikh Sarai, Badli-ki-Sarai and Katwaria Sarai.

A range of merriments were offered along the way. Qawalis and dances marked the journey. Fire dancers also performed on the way to add to thrill. When the procession passed through the streets of Mehrauli, Mughal Emperor Akbar Shah II watched it from the balcony of Zafar Mahal.

In recent years, some new features had been introduced to add to the festival’s charm and offer it a new look. Several cultural troupes joined to perform songs, dances and drama as part of the main function that is held at Jahaz Mahal in Mehrauli. The Mahal or palace was built during the pre-Mughal era of the Lodis and was christened as Jahaz (ship) because its reflection on the nearby water body, Hauz Shamsi, looked as such.

The annual performances at the Mahal reminded all that though stressed, the ship was never going to sink. Quite like the destiny of Delhi.

The festival was observed till 2019 even as Delhi changed prime ministers and chief ministers, hosted leaders dabbling in communally charged speeches and witnessed communal riots.

Over the last two years, Delhi has stayed much the same minus Phool Walon Ki Sair.