- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

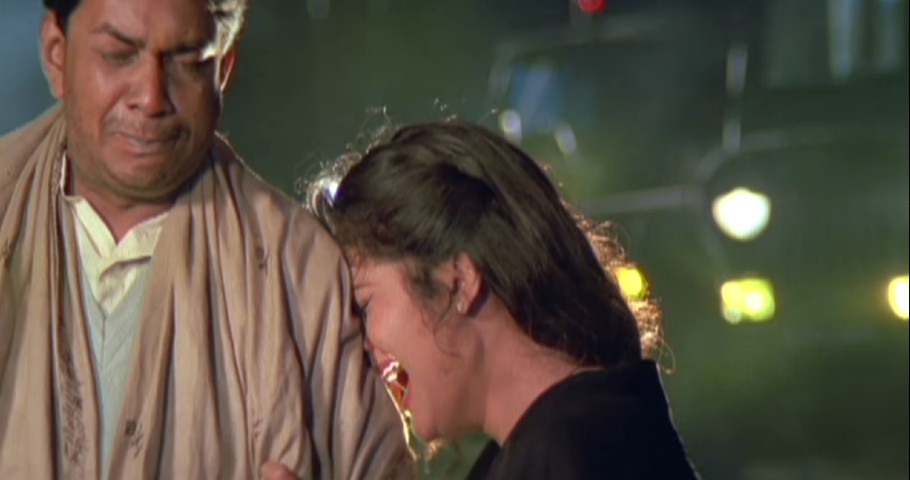

Roja and the making of a whole new generation of nationalists

Wittingly or not, Mani Ratnam’s acclaimed film Roja, released on August 15, 1992, about a woman's battle to get her abducted husband back from Kashmiri terrorists set the trend for more such one-sided ‘patriotic’ movies.

About 55 minutes into Mani Ratnam’s Roja, newlywed couple Rishi (Arvind Swami) and Roja (Madhu) find themselves all alone, surrounded by the snow-kissed peaks and the clear blue skies of Kashmir—Puthu Vellai Mazhai (Yeh haseen vadiyan, yeh khula aasmaan, the Hindi version of the song). As Roja—who has never experienced snow before—slips, trips and falls on the snow, she also...

About 55 minutes into Mani Ratnam’s Roja, newlywed couple Rishi (Arvind Swami) and Roja (Madhu) find themselves all alone, surrounded by the snow-kissed peaks and the clear blue skies of Kashmir—Puthu Vellai Mazhai (Yeh haseen vadiyan, yeh khula aasmaan, the Hindi version of the song). As Roja—who has never experienced snow before—slips, trips and falls on the snow, she also falls passionately in love with her husband.

In a way, this scene—love blooming in the verdant Valley—epitomised the image of Kashmir portrayed in Indian films—a land of dreams and dreamers, of lovers and honeymooners, of beauty and limitless possibilities.

For ordinary movie-goers of the pre-1990s, Kashmir was synonymous with heaven on earth. Apart from the famous proclamation by the 17th century Mughal emperor Jehangir—Gar Firdaus bar-rue zamin ast, hami asto, hamin asto, hamin ast (If there is a heaven on earth, it’s here, it’s here, it’s here)—the images evoked in Indian cinema particularly sealed that idea of Kashmir for most Indians. Tamil Nadu was no exception.

The 1961 film, Then Nilavu (Honeymoon), starring Gemini Ganesan and Vyjayanthimala, was the first South Indian film to be shot in Kashmir.

Although filmed in black and white, the CV Sridhar-directed movie was the first to transport the Tamil audience to the idyllic valley and the famed Dal Lake and its shikara rides. The romcom was one of the biggest hits of that year. Old-timers still admit that the film had such an effect on the youths of the time that everyone dreamed of a honeymoon in Kashmir.

There were many more films after Then Nilavu wherein Kashmir and romance blended smoothly. Even if not entirely shot in Kashmir, it became a norm to capture the beauty of the land through a dream sequence song. And then came Mani Ratnam’s Roja that hit the screens on August 15, 1992.

Changing times

Between 1961 and the summer of 1992, a lot had changed across India and in Kashmir. In the late ’80s, a tidal wave of militancy and popular uprisings swept the Valley. In 1991, while Kashmir was smarting from the Kunan-Poshpora incident (the alleged mass rapes by armymen in two villages of Kashmir), the rest of the country was in the cusp of economic liberalisation. By the summer of that year, the Valley was in the grip of full-fledged armed rebellion.

Amid all this, noted filmmaker Mani Ratnam decided to dish out the beauty of Kashmir but with a contemporary tale.

Initially, released in Tamil, the overwhelming reception to the film made the makers of Roja dub it in all south Indian languages and later into Hindi. With that, Mani Ratnam, too, shot to national fame.

The film in many ways, was a pathbreaker. Famous Tamil writer Sujatha started to write dialogues for Mani Ratnam from Roja onwards. The soul-stirring music by AR Rahman made the Indian cinema and cine-goers turn towards Kollywood. Santhosh Sivan’s mind-blowing cinematography took Roja to another level.

All these things came together to tell an old story—of love in times of trouble—in a new format. The film went on to win the National Award for the Best Film on National Integration besides Best Music Direction and Best Lyrics.

Those who follow the works of Mani Ratnam would know that in his earlier films he used Indian mythology as a canvas to weave and paint his art. Thalapathi (1991) is one such example. He used the friendship of Karna and Duryodhana from Mahabharatha to portray the friendship of Surya and Devaraj.

Roja, too, had a mythological backdrop—the tale of Sathyavan and Savithri, in which the latter rescues her husband from the clutches of Yama (the god of death).

The good Indian wife

In Roja, the eponymous heroine takes up the cudgels to save her husband from terrorists.

The story of Roja revolves around a very limited set of characters. Rishi Kumar, a cryptologist based in Chennai, who helps the Indian Army in coding and decoding, comes to Tirunelveli to marry a girl. Till the first half of the film, Rishi is shown as an ideal middle-class youth, which many young girls “dreams” of getting married to. A person who knows about the (then) complicated world of computers, a person who smokes in front of his mom, someone who owns a white Maruti 800 car and, above all, speaks English.

Besides the technical breakthroughs, the film was also noted for portraying a woman as the protagonist in the ‘good versus evil fight’. But Roja’s heroism is limited to saving her husband’s life and well within the shackles of Indian sanskar (culture). A ‘pattikaatu’ (village girl) who is ‘trapped’ into marrying Rishi, who had initially come to the village to marry her elder sister. But since the sister happens to be in love with another man and pleads with Rishi to turn down the alliance, he decides to marry the younger sister.

While Roja isn’t interested in getting married, nobody thinks her consent matters. As the story progresses, the film subtly justifies that as “everybody else but Roja knew what’s best for her”. Roja, who for long believed that her husband betrayed her family and her sister, suddenly changes her mind after a phone call from the sister who tells her how Rishi turned down the alliance on her request. After that, Roja comes and tells her husband how her sister told her that Roja should instead worship her god-like husband.

Soon after, Rishi is required to go to Kashmir as his boss is unwell. On being asked whether he has any issues given that he is newly married, Rishi happily agrees and says, “Even Kashmir is in India”.

In Kashmir, the village girl gets her first experience of a paradise entwined in terrorism. After getting out of the airport, she asks why the streets are isolated, Rishi says “that’s curfew”. A naive Roja asks what that means, and Rishi says it is to keep the terrorists at bay.

As Rishi gets kidnapped, Roja fights a rather inconsiderate system to get her husband back from the terrorists who want their leader Wasim Khan (Shiva Rindani) to be released in exchange.

Fighting the tough fight

She screams at the police in a language they don’t understand, and fights adamantly with an Army officer (Nasser) to get everything done for her husband’s release. She is bold enough even to meet Wasim Khan in prison and demand her husband back.

On the other hand, Rishi starts a conversation with his captor, Liaqat Khan (Pankaj Kapur), trying to reason with him and convince him to leave terrorism and join the mainstream. But Khan is unmoved, even after his brother and others are killed in cross-fire by Pakistani forces.

The most poignant moment in the movie is when the terrorists are shown burning the tricolour, and Rishi, despite his hands and feet tied, rushes to put out the flames. In the process, his clothes catch fire and he is beaten up. The scene with its heart-rending background score moves one and all.

The film is all about Roja’s determination against all odds to get her husband back, even if at the cost of ‘national interest’.

She doesn’t want to listen to the army officer’s argument that Wasim Khan is a notorious terrorist who has killed many innocents and would go on to kill more, if released.

Rishi, on the other hand, is an all-sacrificing, ready-to-die-for-the-country hero.

Not a complete picture

For a person like this writer, who was born and raised in the Nilgiri hills of the Western Ghats beside the Wellington military barracks, and where a good part of the film was shot, the narrative of Roja created quite an impact.

After the film was released, the people’s perception about Kashmir started to change. It was no longer a dream land for honeymooners, let alone tourism.

For them, Kashmir became a land of terrorists where Indian tourists get kidnapped at the drop of a hat. (According to some film reviewers of the time, Roja was loosely based on the kidnapping of Indian oil executive director K Doraiswamy by Kashmiri militants while his wife fought for his release.)

However, over the years, the once much-hailed film has come under criticism for stirring faux nationalism with the help of brilliant storytelling, music and cinematography.

Kashmir from the Indian gaze

Critics point to the gross misinterpretations that could be drawn from Roja. The key among them was how the film, which although it tries to humanise the Kashmiri militant, doesn’t give much voice to Kashmiris and sees Kashmir from the Indian gaze.

All along, the Army and the state are shown to be upright, sacrificing and securing the lives of common man. In all this, the film completely ignores the plight of the Kashmiris living under the shadow of guns and constant fear. The constant vigil by Indian forces and the alleged atrocities by them find no mention in the movie.

The film doesn’t attempt to tell its viewers why the paradise on earth turned into a valley of violence. It just restricts the militants’ voice to an unexplained “quest” for azadi (freedom) from the mainland.

“The film’s major drawback is that it doesn’t accept the fact that there is a problem,” says Rajan Kurai Krishnan, film scholar and associate professor, School of Culture and Creative Expressions, Ambedkar University, New Delhi.

According to writer and film critic Deepa Janakiraman, times as well as the audience’s sensibility have changed in the past three decades. “Now, people are more aware and tend to compare a film with the real scenario.”

Janakiraman is right. While films are a reflection of society, they can also influence the views of people, especially the young, impressionable minds. With the mercurial rise of pop nationalism and the recent string of ‘patriotic’ movies, Roja and the portrayal of Kashmir holds significance even now, more than ever.

There are always two sides to a story, Krishnan argues. “Roja is very one-sided and fails to tell the other side of the Kashmir story.”

Wittingly or not, he adds, Mani Ratnam’s Roja set the trend for more such one-sided ‘patriotic’ movies.