- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

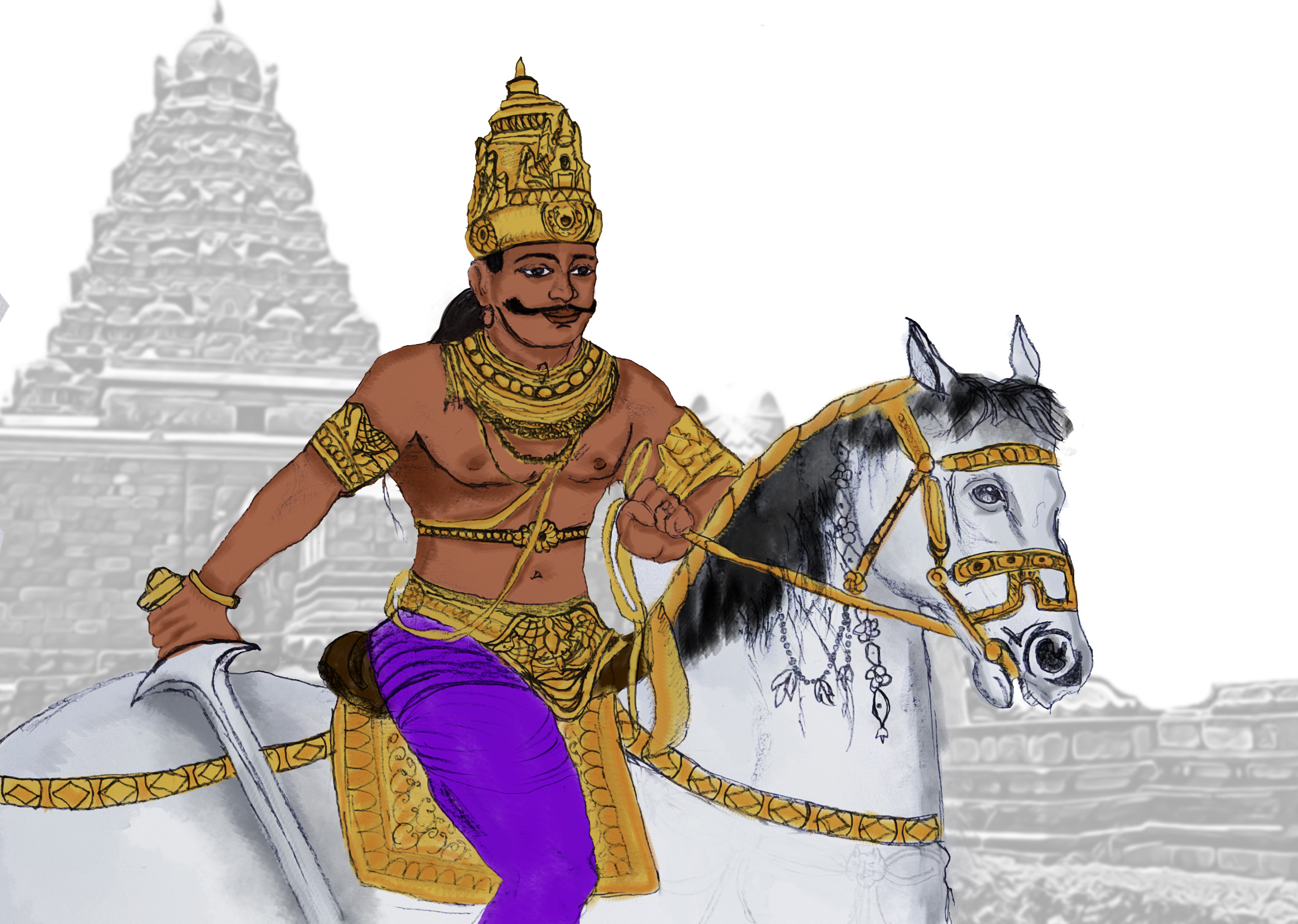

Remembering Rajendra Chola I, greater of the greats

With the help of his three sons, Rajendra Chola was able to spread his kingdom far and wide across India and even across the seas.

An inscription found in 1923 in an old Uruni Alwar temple in Kalakkattur hamlet in Tamil Nadu’s Kanchipuram describes a meeting between a local chieftain named Kadan Mayindan and the Chola king Rajaraja. Kadan Mayindan wanted Rajaraja’s permission for an endowment for setting up a perpetual lamp for the welfare of the king. “In those days, it was impossible for a chieftain to meet...

An inscription found in 1923 in an old Uruni Alwar temple in Kalakkattur hamlet in Tamil Nadu’s Kanchipuram describes a meeting between a local chieftain named Kadan Mayindan and the Chola king Rajaraja. Kadan Mayindan wanted Rajaraja’s permission for an endowment for setting up a perpetual lamp for the welfare of the king.

“In those days, it was impossible for a chieftain to meet an emperor. But being a magnanimous king, Rajaraja invited him to his place Thanjavur, then capital of Cholas, and spent a whole day with him,” says well-known archaeologist Kudavayil Balasubramanian.

When the chieftain put forth his request, Rajaraja thought for a while and said instead of one, he would give grants for two lamps. One, for the welfare of the village and two, for the prosperity of all kings and the world at large.

A note published in the Annual Report of Epigraphy published in 1923, describes further about the inscription: “The inscription records the setting up of a lamp in the temple at Kalakkattur by a certain chief called Kadan Mayindan for the welfare of the king and of the whole earth, at the instance of no less a person than the king himself. The chief says that as his royal master himself was so pleased to order the grant of one lamp that he would give two instead of one.”

Balasubramanian adds that Kadan Mayindan after returning, set up an endowment for three lamps—two lamps as per the wishes of the king and one according to his wish, i.e., for the welfare of Rajaraja.

“Rajaraja wanted to light a lamp for the welfare of all the kings on earth. What is a bigger democratic view that a monarchic king can have than this?” asks Balasubramanian.

This is why medieval Cholas are still remembered over other kings—not only for their power and valour, but also because of their benevolence and the nature of treating other kings, even those captured after war, in a well-mannered way. And for this reason, Tamil and other people celebrate Rajaraja’s birthday in a grand manner.

“While there are no records about celebrating the birthdays of other kings such as Chera or Pandya, there are records that people continued to celebrate the birthday of Rajaraja even after his death,” says Balasubramanian.

Since Rajaraja was born in the seventh month of Aippasi (mid-October to mid-November) as per the Tamil calendar and under Sadhaya star, his birthday is celebrated as ‘Sadhaya Vizha’.

The Tamil Nadu government too started celebrating his birthday as a government function from 2010. Since then, there has been a widespread demand from historians that Rajaraja’s son Rajendra Chola’s birthday too must be celebrated as a government function.

Acting on the demand, the state recently announced that Rajendra’s birthday, ‘Aadi Thiruvathirai’ (Aadi is the fourth month of Tamil Calendar and falls between mid-July and mid-August. Thiruvathirai is the birth star of Rajendra), will be celebrated by the government in a grand manner from next year.

While Sadhaya Vizha is celebrated at Thanjavur Big Temple, since it was constructed by Rajaraja, Rajendra’s Aadi Thiruvathirai is to be celebrated at Gangai Konda Cholapuram, his capital in Ariyalur district, which now is shorn of all its grandeur.

Golden era of Cholas

The Cholas ruled what is now Tamil Nadu between 300 BCE and 1279 CE. Scholars categorise Cholas into four time periods—Cholas before Sangam Age, Cholas during Sangam Age, Medieval Cholas and Later Cholas. As records related to the first two periods are minimal, we are unable to know much about their rule except the names of some kings.

However, it was from Medieval Cholas that we have proper records. The Chola dynasty in its fullest sense lasted for 433 years between 846 CE and 1279 CE. King Vijayalaya Chola was the first king of the dynasty during this period and King Rajendra Chola III was the last.

Much about Chola history is known through stone inscriptions, copper plates, monuments, literature, coins and texts of foreigners.

The significance of this, according to Balasubramanian, is that the Cholas were conscious about their history and hence they recorded every major incident, so that the future generations can know. “This consciousness is missing in the other two dynasties,” he says.

“Vijayalaya Cholan, who ruled for 35 years, was the first king in the medieval period. It was claimed he had 96 wounds in his body, all because of the wars he had waged,” says historian Rajasekara Thangamani in his book ‘Rajendra Chola’.

In 880 CE, there was a bloody war between Pallava and Varaguna Pandya held at Sri Purambiyam, near Kumbakonam in modern day Thanjavur district. In this war Vijayalaya supported Pallava, says Thangamani.

“This war was a turning point in Tamil Nadu history. Known as the ‘Battle of Thirupurambiyam’, this war can be equated with the wars waged by Pandyan Nedunchezhiyan’s Thalaiyalangaana War, Karikaal Peruvalathan’s Venni War, Babar’s First Panipat War, Robert Clive’s Battle of Plassey. Following the war, Cholas regained their regime,” writes Thangamani.

Rajaraja Chola

About 140 years later came Rajaraja Chola. His maiden name was Arunmozhi Devan. Although the medieval Chola time is generally said to be a golden period, the period of Rajaraja is considered the best.

According to historian KA Nilakanta Sastri, with the accession of Rajaraja, we enter upon a century of grandeur and glory for the dynasty of the Cholas.

“Quite obviously, the personal ability of the first Rajaraja, in some respects the greatest of all great Chola rulers of Vijayalaya line, laid the foundation for the splendid achievements of his son and successor Rajendra I, under whom the empire attained its greatest extent and carried its arms beyond the seas. The 30 years of Rajaraja’s rule constitute the formative period in the history of Chola monarchy,” says Sastri.

In the organisation of the civil service and the army, in art and architecture, in religion and literature, we see at work powerful forces newly liberated by the progressive imperialism of the time, he adds.

Great son of a great father

Rajaraja crowned his son Rajendra Chola I, in 1014 CE. However, Rajendra had started taking part in governance from 1012 CE as a prince. It was Rajaraja who first introduced the joint-rule system.

“Between 1014 CE and 1022 CE, Rajendra did three major things simultaneously. One, setting up of a new capital, two, waging war inside India and three, invading foreign countries,” says Balasubramanian.

The old capital of Cholas, Thanjavur, was a land of farms. Rajendra found it insufficient for his large army. So he chose the present day Ariyalur as his capital. To sustain life, he built a new tank and brought water from Kollidam and Vada Vellar rivers through canals. The excess water was drained into Veeranam lake.

“With the help of his three sons, Rajendra was able to defeat other dynasties within India and capture places in what is now Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal and Bangladesh. From Tribeni in Bengal, he took the Ganga water to solemnise his new capital and that’s how the capital came to be known as Gangai Konda Cholapuram and Rajendra was given the title ‘Gangai Konda Cholan’. Like his father, Rajendra too built a Big Temple in Jayankondam, Ariyalur,” says Balasubramanian.

The Cholas also dominated trade during those times. However, before Rajendra, traders feared to carry out maritime trade because of pirates. Rajendra changed all that.

“By invading countries like Maldives, Indonesia and Malaysia, Rajendra established his power in those countries and thereby created a fear among pirates. It was achieved by his powerful naval force,” claims Balasubramanian, arguing that this was why the Indian Navy celebrated the 1000th anniversary of Rajendra’s coronation in November 2014.

After every victory in war, the Cholas made it a practice to create a ‘Meikeerthi’, or inscriptions eulogising the valour of the king and the places he captured before writing any document.

“Rajendra’s war victories were recorded only from his fifth year of his rule. It goes on till the 13th year. The Thiruvalangattu copper plate and Karandhai copper plates are rich sources of information,” says Thangamani.

Rajendra’s wars also helped spread Tamil culture to northern states. He even brought Shaivite Brahmins to Thanjavur and Kanchipuram, ensuring the mingling of Tamil Shaivism with Saivism from other parts of the country. Interestingly, during the Chola period, students were taught northern languages too. Rajendra also introduced the concept of administration by viceroys in the countries he won, Thangamani adds.

Balasubramanian in his book ‘Rajendra Cholan’ records that contrary to popular perception that Brahmins were given lands by the Chola kings, they were paid only in rice or coins.

“The donations Rajendra made to Brahmins were known as “shares”. They were paid from government revenues only,” he said.

A push for tourism

It is interesting to note that until 1988, there was a confusion among historians about the birth month of Rajendra. Balasubramanian, while working for his book ‘Tiruvarur Thirukkovil’, collected 91 inscriptions of which, the 70th inscription clearly mentioned that the birth month of Rajendra was Aadi.

“Even Nilakanta Sastri safely played that the birth star of Rajendra was Thiruvathirai but remained silent on the birth month,” says Balasubramanian.

The Tamil Nadu government’s announcement to celebrate Rajendra’s birthday has given hope to the people of Ariyalur to improve the economy of the region by boosting tourism.

R Komagan, chairman, Gangai Konda Cholapuram Development Council, says that the place which served as a capital of Cholas for 267 years has now been reduced to a panchayat.

“It is only through such kind of government functions, the importance of the place and the achievements of the king can be taken to the world. Moreover, the Peruvudaiyar temple located here has been recognised as a world heritage site by UNESCO in 2004. After UNESCO’s announcement people started visiting here in large numbers. We hope, by the recent announcement of the state government, the numbers will go up and it will be a shot in the arm for tourism,” he says.