- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

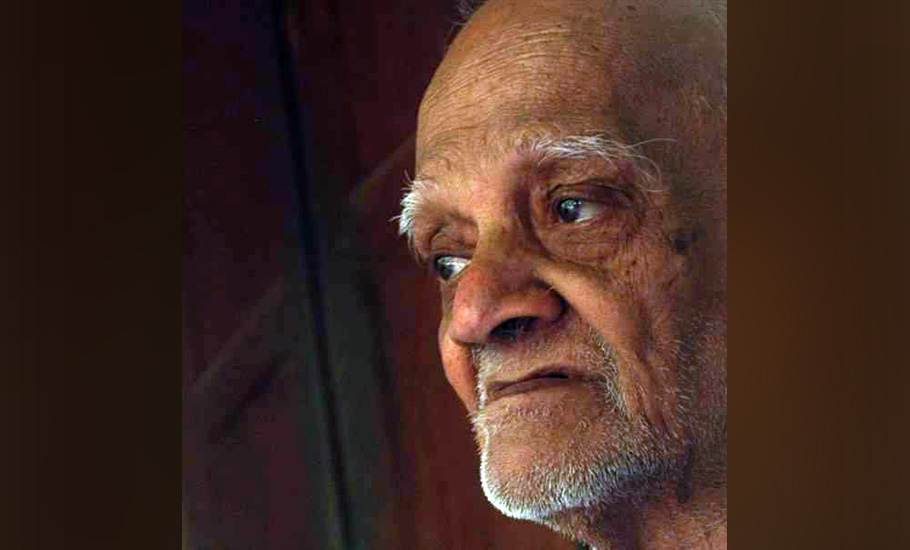

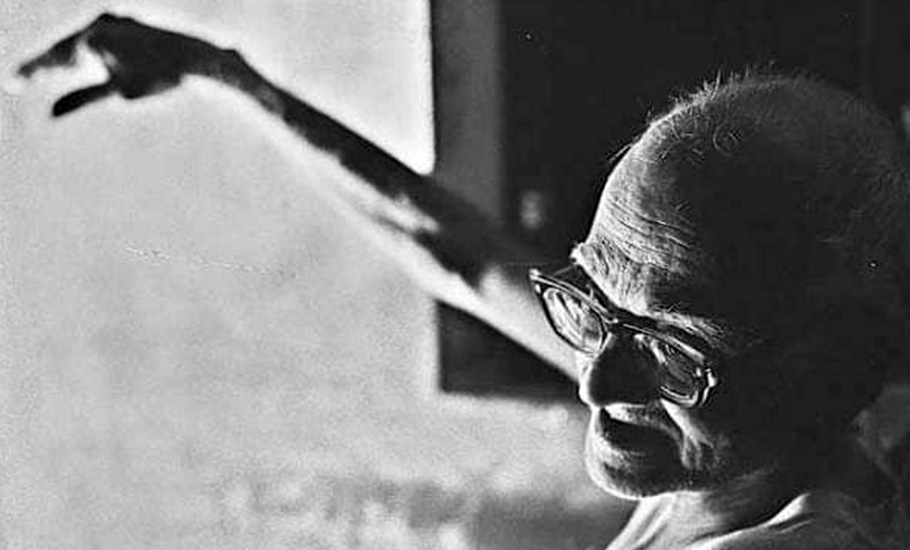

Remembering Nakulan: A poet-writer, his free verse and an imagined lover

If you feel a void in your heart, you will feel Nakulan’s words. They can fill that emptiness through his novels and poems.

“Naveenan is my name. I have been doing some writing for the past twenty five years. Not published a thing. That may be wrong—some fifteen pieces have been published so far, short stories, novels, poems. I didn’t receive any remuneration for thirteen of them. There was a cheque for the fourteenth and the amount realised after bank charges was four rupees and twenty five...

“Naveenan is my name. I have been doing some writing for the past twenty five years. Not published a thing. That may be wrong—some fifteen pieces have been published so far, short stories, novels, poems. I didn’t receive any remuneration for thirteen of them. There was a cheque for the fourteenth and the amount realised after bank charges was four rupees and twenty five paise.”

The opening lines from poet-author Nakulan’s short story, ‘A Pound of Mutton’, are enough to offer a glimpse into the lives of most writers—underpaid, unspirited yet writing undauntedly.

According to popular writer Ashokamitran, who translated ‘A Pound of Mutton’ from Tamil to English, only a handful of writers can afford to live their life without distancing it from their writing. And Nakulan, he says, was one of them.

Those lines capture the typical Nakulan. He wrote a lot but he read far more, say those who knew Nakulan well. He was read by an eclectic bunch of readers, mostly because he broke all ‘rules’ of storytelling—both in theme and structure but without losing the purpose.

Most of his works are considered avant garde, or experimental. As K Sivathamby writes in The Growth of the Novel in India, 1950-1980—a collection of essays, edited by PK Rajan—“as is indicated by the semantics of the term, they (avant garde novelists) go for the latest techniques and themes. It also implies that they draw inspiration from writers who have earned that description in the Western world.”

Nakulan, who wrote both in Tamil and English, too drew inspiration from western writers like Samuel Beckett, James Joyce and Franz Kafka.

According to Sivathamby: “In the Tamilian context, avant-garde novelists have always been more concerned with the form and technique than with the theme. Nevertheless, there are two novelists from this group who deserve special mention. They are Ashokamitran and Nakulan. Both have allowed their novels to be described as ‘symbolic’.”

Sivathamby, however, felt that the “main problem with the avant-garde Tamil writers has been that they have not yet succeeded in striking an indigenous note in their symbolism”.

Probably, it was this missing “indigenous note” that prevented Nakulan from hogging the limelight, unlike many of his contemporaries. However, his contribution to Tamil literature is no way less than any of the literary giants from the state.

It is precisely why Nakulan’s novels are loved by readers even today, 100 years since he was born. But it’s not just his novels, his personal life intrigues his readers equally.

A life spent well, and alone

Born as TK Doraiswamy on August 21, 1921 in an orthodox Tamil Brahmin family in Kumbakonam, Nakulan’s family moved to Thiruvananthapuram when he was 14.

He did his post-graduation in Tamil from Annamalai University and, again in English, from the University of Kerala. He also did an MPhil on the modernist writer Virginia Woolf’s work, focusing on the ‘stream of consciousness’ method that she used—what is called the indirect interior monologue—in her writing. Then, for the next four decades, Nakulan worked as an English professor at Mar Ivanios College, Thiruvananthapuram.

Always dressed in a white shirt and dhoti, Nakulan led a solitary life. Although he wrote a lot about his imagined lover Suseela in most of his works, he never married.

“Although he had three brothers and two sisters, he was alone. He never complained about this,” writes writer-translator Sukumaran in an obituary published in May-June, 2007 issue of the Indian Literature, Sahitya Akademi’s bimonthly journal.

According to Sukumaran, Nakulan lived alone by choice. So that he could dedicate his entire time to literature. And he did so. “He wrote. He read. These two acts mainly constituted his life.” And this lifestyle made him a recluse. He travelled through his own mindscape that was imperfectly lit, lonesome but uncompromising. These qualities of his personal life are reflected in all his works—be it poetry, short stories or novels, Sukumaran adds.

While he wrote under his own name in English, he used the pen name Nakulan for Tamil. He published a novel, Words for the wind (1983) and six poetry collections in English—Words to the Listening Air (1968), Non-being (1986), and A Tamil Writer’s Journal I, II and III (1984 – 1989). He also translated Tamil poet Subramaniya Bharathi’s poems into English as The Little Sparrow (1982).

His Tamil works include five poetry collections and eight novels—Nizhalgal (1965), Ninaivu Paathai (1972), Naaigal (1974), Naveenan Diary (1978), Ivargal (1983), Sila Aththiyaayangal (1983), Vaakkumoolam (1992) and Andha Manjal Nira Poonaikkutty (2002).

“Nakulan was fondly called the ‘writer of writers’. It may be a cliche. But it did suit him in its real sense. Because he had found his own path and reached his own realm in modern Tamil literature. In this aspect, he could be compared with the short story writer ‘Mauni’—the first writer’s writer. No Tamil writer other than these two could enjoy the privilege of having this cliche associated with one’s name,” says Sukumaran.

The mysticism

Nakulan was also seemingly inspired by the writings of popular Tamil writer and critic Ka Naa Subramaniam. Of course, Subramaniam was a role model to many writers of the time.

In fact, it was Subramaniam, who gave space to Nakulan’s writings in literary magazines such as the Ilakkiya Vattam, of which Subramaniam was the editor, and also in Ezhuthu, edited by CS Chellappa. Like many other writers, Nakulan too started with poems.

It was a time when literature was at a crossroads. New trends were emerging in the literary arena. Tamil poetry, in particular, witnessed a renaissance—Puthu Kavithai. It was a new wave that brought about a poetic revolution in Tamil. N Pichamurthy experimented with his writings and it resulted in the birth of a new movement in Tamil poetry. With a good number of enthusiasts, Nakulan too contributed to the change, writes Sukumaran.

His poem in free verse—’Kollippavai’ (The Siren) — published in Ezhuthu left an indelible impression on the reader’s mind. Although the poem was based on an ancient story, the expressions and the intellectual content were very new to the poetic environment, he adds.

“Nakulan continued with this style until his very last poem. He had experimented with words, sounds and images which continues to inspire new poets to experiment with their verses. This could be a reason why he was one of the most sought after literary figures among new age writers and poets,” Sukumaran says.

Nakulan’s poetry assumed deeper meaning with his unusual style. For instance:

Between the

writer and

the reader

words stand

as a

b

a

r

r

i

c

a

d

e

(எழுத்தாளனுக்கும்

வாசகனுக்கு

நடுவில்

வார்த்தைகள்

நி

ற்

கி

ன்

ற

ன!)

(Translation—Chenthil)

One wonders when the words should have acted as a bridge, how could they become a barricade? Whether a writer is able to convey the message they want to? Or the reader can read between the lines?

We come

here to be

and leave

without being.

(இருப்பதற்கென்றுதான்

வருகிறோம்

இல்லாமல்

போகிறோம்!)

(Translation – Chenthil)

Kavya Shanmugasundaram of Kavya Publications, which brought out Nakulan’s poetry collections in one volume, says in the preface that when Nakulan writes about his life experiences in his own way, one can see big bold traces of mysticism.

“Categorisation will be impossible with Nakulan’s poems. They are sometimes free and simple. Sometimes complex. His poems like ‘Kollippavai’, ‘Coat Stand’, etc., are examples of the complex nature of his poetic mind. ‘Mazhai Maram Kaatru’ (Rain, Tree and Wind) is deceptively simple. His poems like ‘Moonru’ (Three), ‘Ainthu’ (Five) are inspired by the Ramayana. They deal with ancient human predicaments in the contemporary background,” says Sukumaran.

They are, he adds, classical in form and modern in content. Some of his poems are surrealistic. For instance, this line from one of his poems: ‘He was sharpening the pencil like severing somebody’s head.’ In some poems, a riddle-like quality could be seen. “I mention all this to establish that Nakulan could not be put into any one category, as he had developed his own genre in literature, because of his enigmatic life,” adds Sukumaran.

Thoughts become things

Although Nakulan’s poems are well-received mostly because of the brevity, his creativity is on full display in his novels. His Ninaivu Pathai (Memory Lane) is considered to be the first Tamil novel that explored the ‘stream of consciousness’ method. It’s neither an autobiography nor a fiction, but traverses both realms. It is a sort of memoir with both imaginary and real characters in it.

In Ninaivu Pathai, the author talks about himself, his friends Sivan and Natarajan, and his imagined lover Suseela.

“There is no story or characters as one can see in a conventional novel. It is mostly about what is going on in his mind. He constantly touches upon the existential question. Somewhere he inquires about life,” says poet Shankarramasubramanian.

Similarly there are no individual characters, who take the story forward. All the characters are part of the situation, he adds.

“For example, who is Shankar?” asks Shankarramasubramanian.

“I am a creation of my father, mother, teachers, musicians, the books I read, the films I saw, etc. So, we all are a reflection of something. We all are a part of a collective society. Nakulan inquired about this notion of ‘self’. That is why he was able to ask ‘why can’t Naveenan be called a dog?’.”

Because Nakulan believed that a man could very well be a reflection of a dog. “Naveenan is an alter-ego of Nakulan,” says Shankarramasubramanian, who is now working on a book on Nakulan.

If you feel a void in your heart, you will feel Nakulan’s words. They can fill that emptiness, he adds.

His other novels, too, experimented with this ‘stream of consciousness’ and that is why writer S Ramakrishnan, in one of his articles, says Nakulan has written eight novels or “we can say he wrote different parts of one novel eight times over”.

In Vaakkumoolam (Confession), he writes about a government’s new idea of ending people’s life after the age of 60 through ‘National Development Act 286’. While Naaigal (Dogs) deals with the question why people get angry when compared to a dog, Nizhalgal (Shadows) talks about generation gap and the role of family in shaping or destroying an individual’s life.

“Sadly, none of these novels were published by any big banner. They are distinctly different from one another. They do not have a storyline, which is considered a must for a work of fiction. His novels are voyages through the human mind. Exploring the human mind is an unending task. But Nakulan effortlessly took over the task in his writings,” says Sukumaran.

Having been born in a Tamil family, living in a neighbouring state and teaching a foreign language—all this added a unique colour to his writings, which are neither bound by geographical frontiers nor by language, he adds.

“He created a mindscape which is incomparable. He created an idiom in the language which is inimitable. And this makes Nakulan distinctive.”