- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Ram in Bengal: Why the truth is far from what the Right or the liberals claim to be

Five years ago, the then Bengal BJP chief Dilip Ghosh infamously declared that Ram Navami celebrations in the state was a fight between “Ramzada” (one born of Lord Ram) and “Haramzada” (illegitimate-born). Ever since, armed processions to mark the Hindu religious event have always spooked the state. That was the year when the saffron party decided to establish...

Five years ago, the then Bengal BJP chief Dilip Ghosh infamously declared that Ram Navami celebrations in the state was a fight between “Ramzada” (one born of Lord Ram) and “Haramzada” (illegitimate-born). Ever since, armed processions to mark the Hindu religious event have always spooked the state.

That was the year when the saffron party decided to establish the “birthday” of its biggest political linchpin as one of the dominating religious events of the state.

Youths sporting saffron bandana with ‘Jai Shree Ram’ inscribed in Hindi trooped the streets on their bikes, wielding swords and chanting “UP boley Jai Shree Ram, Bangal Boley Jai Shree Ram,” keeping the state on tenterhooks.

Even though the never-seen-before spectacle passed off without any major untoward incident in 2017, a year later, the similar show of saffron strength took an ugly turn as communal clashes broke out in Asansol and other areas of the state during the Ram Navami celebration.

Ram Mandir Mahotsav Samiti took out a procession on the occasion of #RamNavami where people were seen brandishing swords, in West Bengal's Siliguri pic.twitter.com/UZudBIo0Hn

— ANI (@ANI) March 25, 2018

The BJP’s effort to polarise the state in the name of Lord Ram did bring political dividend in the land of female deities – Durga, Kali and pantheons of subaltern goddesses such as Chandi, Manasa, Shashthi and Jagaddhatri – as was evident in the 2019 general elections. It sprang a surprise winning 18 of the state’s 42 Lok Sabha seats with a whopping 22.76 per cent rise in vote share. The result changed the political landscape of Bengal, propelling the BJP as a dominating force in the state politics.

The ruling Trinamool Congress and the CPI (M) were quick to point out that the BJP was using Ram Navami to create division in the society to increase its influence in the state.

It was, however, not the first time an attempt was made to mainstream Ram in Bengal to propagate a particular thought. Much before that when Vedic Hinduism was slowly developing in the region, co-opting local folk religions and customs, Ramavats form of Vaishnavism was practised.

A century before Tulsidas wrote Ramcharitmanas in local Awadhi language popularising Ram as an epic hero in the Hindi heartland in the 16th century, medieval Bengali poet Krittibas Ojha penned Sri Ram Panchali or the Bengali Ramayana.

But the Bengali version of the Ramayana was not a verbatim translation of the original Sanskrit text.

“It tells more about life and culture of Bengal in the 15th century. There was also this improvisation of Ram worshipping Durga before going to the battle against Ravana,” pointed out professor Dr Anusua Roy Choudhury.

It also delved on the concept of Bhakti and is believed to be the precursor to the establishment of Vaishnavism in Bengal and surrounding region. “So, in a way Krittibas’s Ramayana was an extension of the Mangal Kavyas. Only here the central character is not an indigenous deity as is the case in Mangal Kavyas,” she added.

Mangal Kavyas are Bengali religious ballads mostly composed between 13th and 18th centuries as an ode to indigenous deities. They also extensively described the social scenario of the then Bengal just as the Sri Ram Pachali of Krittibas Ojha.

Social anthropologists are of the view that these religious texts were actually an effort by Brahmanical elites to reach out to the subaltern classes by co-opting their deities into the larger Hindu fold to prevent their conversion to Islam.

Later, as the Gaurio Vaishnavism was popularised by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, a 15th-century saint, Ram was slowly replaced by Krishna in the Bengali Hindu consciousness. Although ‘Hare Krishna, Hare Rama’ is said in the same breath by Vaishnavite devotees, they mostly worship Krishna as their presiding deity.

Going by the frenzy whipped up over Ram Navami in the recent past, many in the state are now convinced that the BJP and its extended Hindutva family are again trying their best to project Ram as a central figure of Bengali Hindu religion. But the growing clamour for Ram hasn’t gone well with many, including the state’s intelligentsia, some of whom even went to the extent of claiming that Ram was never a part of the Bengali culture.

“Ram Navami is gaining popularity nowadays. I never heard of it before……I asked my four-year-old grandchild ‘who is your favourite deity’? She replied, ‘Maa Durga’. Maa Durga is so omnipresent in our lives,” Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen was quoted by media as saying at a programme in Jadavpur University in 2019.

That does not mean that Bengalis have completely forgotten Raghubir, (one of many names of lord Ram). He continues to appear in Bengali literature and culture, although not always as an endearing figure.

Chasing the enigma

Tales from the Ramayana are still popular themes in Bengali folk theatres and traditional Chhau dance dramas. Stories from the epic are also found inscribed in the plaques of terracotta temples of Bishnupur and other parts of Bengal, immortalising them for generations.

Besides, there are also centuries-old Ram temples dotting the state’s landscape, mostly in Hooghly, Nadia and Murshidabad districts bearing traces of the past when Ram, unlike today, was a unifying force.

Interestingly, even a city in Bengal – Srirampore – is named after the mythical king of Ayodhya. It is said that Sheoraphuli king Rajchandra Ray had a dream while sleeping on a boat wherein lord Ram instructed him to build a temple. As per the “instruction”, he constructed a Ram temple in 1753 and donated three villages – Sripur, Mohanpur and Gopinathpur – for the purpose. The three villages altogether came to be known as Srirampore.

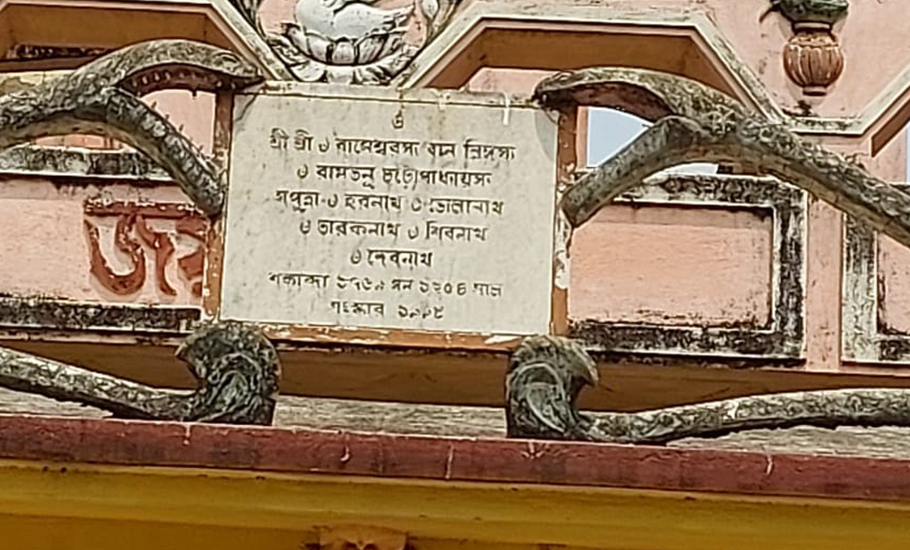

“It is wrong to say that Ram was never worshipped in Bengal and that he was an alien god. Our family has been the custodian of a Ram temple for more than 250 years,” Purushottam Chattopadhyay tells The Federal. Chattopadhyay is a fourth-generation descendant of Ramtonu Chattopadhyay, who built a Ram temple in Uttarpara in Hooghly district around 1797.

“Ramtonu was a very influential zamindar who committed several sins like forceful acquisition of land and punishing those who failed to pay him taxes. But later he felt remorse for his misdeeds and wanted to purge his sins. At that time, a saint advised him to devote himself to religious works. That was when he built the Ram temple,” Chattopadhyay adds.

Since then, the entire Chattopadhyay clan worships Ram as their Ishta-devata — the family deity.

Grand celebrations used to be held at the temple premises even a few years ago. But now the celebrations have been scaled down, says Chattopadhyay, adding that most Ram temples in the state have lost their past glory.

The irony behind political forces propping up the deity leaving his abodes in shambles is not lost on all.

“Ram is now dragged to the streets [rallies] from temples for political gains by all parties,” he adds.

This year, too, Hindutva organisations like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) have made elaborate plans to take out more than 1,000 rallies across West Bengal as part of celebrating Ram Navami on April 10.

Sevaits of state’s existing Ram temples like Chattopadhyay feel that it would have been better had the VHP focused its attention on the condition of the temples.

In the past, even the TMC took out processions on the occasion of Ram Lalla’s birthday, which has now turned into more of a political than religious event.

Considering the growing popularity of such celebrations, this time Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee instructed officials to ensure that no Ram Navami procession, coinciding with the Ramzan (Islamic month of fasting), is disturbed.

From a mythical deity to a cultural icon to now a political linchpin, Ram truly has many avatars in Bengal.