- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

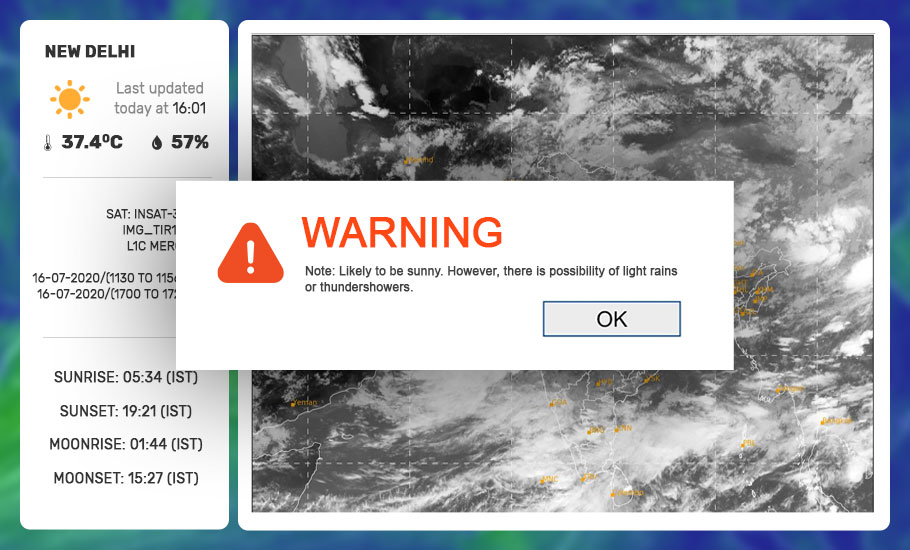

Rain or shine, IMD has been under the weather for a long time now

IMD’s repeated failures have given a leeway to private weather monitoring companies to come up, with a number of state governments hiring private agencies to firm up their plans.

In July 2017, farmers in Beed district of Maharashtra, a drought-prone area in Marathwada region, filed a police complaint against the government-run India Meteorological Department (IMD) for misleading farmers with incorrect weather forecasts during the south-west monsoon. The farmers who were largely dependent on IMD’s forecast for sowing activities even alleged that the department...

In July 2017, farmers in Beed district of Maharashtra, a drought-prone area in Marathwada region, filed a police complaint against the government-run India Meteorological Department (IMD) for misleading farmers with incorrect weather forecasts during the south-west monsoon.

The farmers who were largely dependent on IMD’s forecast for sowing activities even alleged that the department had “colluded” with seed and pesticide manufacturers, and had “inflated” the monsoon forecast figures.

The Beed unit of Swabhimani Shetkari Sangathan, a state-level farmers’ organisation, threatened to lock up the IMD office in Pune as the department’s long range forecast of normal rainfall for the year did not turn out to be true.

Farmers who invested thousands of rupees in seeds, fertilisers, pesticides and farm labourers, were staring at long dry spells after an initial spell of rains, and it threatened the survival of kharif crops such as soybean and cotton.

The state government which took note of the concern, issued an advisory to delay sowing. But this announcement by the then-chief minister Devendra Fadnavis came on July 9, two weeks after several farmers had already started sowing. Fadnavis later wrote a letter to the Ministry of Earth and Science over the wrong predictions and urged the Centre to take measures to improve the accuracy.

The following year, farmers from another village filed a similar complaint against the IMD. These are not isolated incidents. IMD’s predictions have gone wrong multiple times over the years. In one of the worst cases, the department had predicted a near-normal rainfall in 2009, the year India faced one of the worst droughts in four decades.

With erratic rain patterns and changing climatic conditions even at panchayat levels, the standard district-level and state-level weather predictions by the IMD were not catering to the needs and demands of farmers today. With IMD failing to provide localised weather information, it resulted in confusions and also wrong categorisation of yellow, orange, and red alerts.

Private players step in

IMD’s repeated failures have given a leeway to private weather monitoring companies to come up. A number of state governments have started relying on private weather companies to plan agriculture, water and transport management.

Upset with IMD’s repeated failures, the Fadnavis government in 2018 started a public-private partnership with Skymet Weather Services that set up 2,060 weather stations to monitor and disseminate real time information to users.

Come 2020, a similar thing has happened in Kerala. Even as Skymet announced early onset of monsoon in the state considering various parameters like rainfall, wind speed and electromagnetic radiations, the IMD maintained that conditions were not ripe for the declaration.

Kerala has now engaged Skymet Weather Service, IBM Weather Company and Earth Networks on a one-year pilot project at a cost of ₹1 crore to help the state tackle disasters better, having seen two in quick succession in the last three years.

“By accessing the service of the private players, we are only trying to bring value addition and a comprehensive approach by giving more focus to localised forecasts,” Dr V Venu of Kerala Disaster Management Authority had said.

Need for localised information

IMD issues five kinds of forecasts — Nowcast (up to 24 hours), short-range forecast (up to three days), medium-range forecast (3-10 days), extended-range forecast (10-30 days) and long-range or seasonal forecast (monsoons). Many times, the seasonal and short-range forecasts have gone wrong.

IMD last year declared deficit rainfall in its seasonal forecast. In reality, there were six rain-driven floods in the country. A good number of people died due to thunderstorms and there were landslides damaging public property.

Angshujyoti Das, director at Farmneed Agribusiness, says this could be a pocket phenomenon where some pockets receive good rainfall and some receive deficit so a broad forecast might not help.

If we have more weather monitoring stations, the weather can be more localised and accurate

“If we have more weather monitoring stations, the weather can be more localised and accurate. For that the government needs to invest in infrastructure,” says Das.

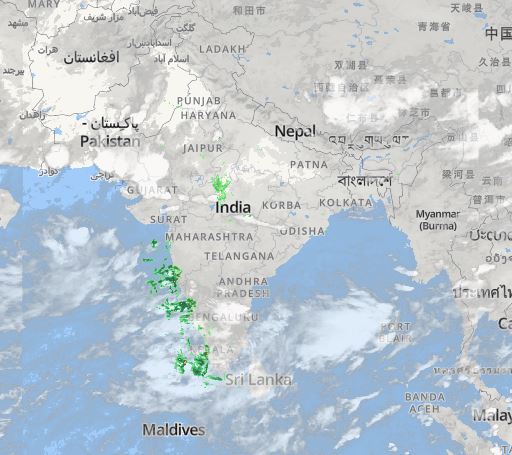

Private players and state disaster management centres in various states have 4-5 times the number of weather monitoring (gauging) stations across the country as compared to IMD, and hence their accuracy is much higher.

For instance, Karnataka’s Disaster Management Centre has 6,500 rainfall monitoring stations across the state, Skymet has about 7,000 stations across the country while IMD has only about 1,200 automatic weather stations (AWS).

Lack of interaction

Experts say another issue is that the IMD doesn’t have an interface with private players and they do not have the scope to integrate and work together to improve the efficiency.

“I think there is a crisis of identity with the IMD. They still think they have a monopoly over the sector. That thought needs to change,” Jatin Singh, CEO of Skymet says.

“They are great regulators and incubators. But they are not really known for services as they are not exposed to competition. A private enterprise can scale differently and serve better,” he adds.

While Singh accepts that no entity can match the national agency in terms of their capability, with the changing dynamics, he says, IMD cannot cater to everybody, and hence, it should become an umbrella organisation under which other players can collaborate and work.

Partnerships that help

On the other hand, the government itself relies heavily on private entities now. For instance, the US-based IBM-owned The Weather Company collaborated with Niti Aayog in 2018 to use artificial intelligence in precision farming. It also conducts on-ground research and provides data to the agriculture ministry from time-to-time. The company launched a global high-resolution atmospheric forecasting system in December 2019 and during the launch, its CEO said their forecasts were 30% more accurate than the IMD’s.

“In the tests we ran, our model is around 30% more accurate (than Indian system) and we have so far designed to issue 12 million pieces of forecast information through IBM GRAF, which will improve the forecast quality massively in India,” Cameron Clayton, general manager at IBM Watson Media and Weather, was quoted by Economic Times as saying.

Similarly, during the Kerala and Andhra floods in 2018, SatSure, a data analytics firm, worked with both the state governments and provided real-time information about affected areas to help in the relief and rescue operations. From locations of hospitals to rescue efforts and extent of floods, the whole thing was visualised on a web-based map for easy access.

Skymet recently partnered with National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange (NCDEX) to launch a weather index and facilitate derivatives trading on the index. The company offers services to insurance companies, banks, telecom giants, disaster management wings in Nagaland and Kerala and five other state governments.

“The field is relatively open. I am solving the agro-meteorological data problems of the government of India, directly or indirectly,” Singh says.

Is IMD stepping up its game?

Though IMD is still the nodal agency for weather related announcements, former director of Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre GS Srinivasa Reddy says one cannot expect them to provide panchayat level information and that has to be the role of state-governments.

IMD too is making attempts to improve its data and forecasting services. It has said that the error margin for monsoon forecasts has declined from 7.94% between 1995 and 2006 to 5.95% between 2007 and 2018.

In collaboration with ICAR, IMD is venturing into implementing block level agromet advisory services. District Agro Meteorological Units (DAMU) are being established in the Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) under the ICAR network. At present, 42 million farmers in the country are receiving Agromet Advisories through SMS directly, the Ministry of Earth and Science claims.

“I am sure IMD predictions are more accurate compared to 20 years before. But it hasn’t improved at a quick pace. The agility is missing,” Das points out.

He suggests IMD should play a support-centric role for developing the weather sector in India.

“Private players cannot come with big investments. So the government needs to improve infrastructure. Then the last mile delivery (of services) will not be a challenge considering the rising smartphone penetration in rural areas.”