- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Politics and theatre: A story of the oppressed in Bengal

“I was murdered today. Yesterday. Day before… I get murdered every day. I will be murdered tomorrow.” Khoka cries out loud. He speaks to the audience and tries to tell the same to a police officer. But his screams fall on deaf ears. The principal character in theatre-great Badal Sarkar’s Michhil (Rally, in Bengali), Khoka, has been the epitome of the oppressed,...

“I was murdered today. Yesterday. Day before… I get murdered every day. I will be murdered tomorrow.”

Khoka cries out loud. He speaks to the audience and tries to tell the same to a police officer. But his screams fall on deaf ears. The principal character in theatre-great Badal Sarkar’s Michhil (Rally, in Bengali), Khoka, has been the epitome of the oppressed, whose woes find no audience, and his suffering, no end. And Khoka dies time and again, daily.

A harsh reminder to the contemporary situation, Michhil and several other plays by Sarkar and other playwrights have shaped modern political or protest theatre in Bengal over the last few decades, and over a century, if we count the pre-Independence movements.

But with changing times, political polarities, and suppression of dissent and throttling of free voice, political theatre in the state has seen several makeovers. Still, what remains is the enthusiasm and unswerving determination of some artistes who are keen on taking forward the legacies of Badal Sarkar and his likes who dared to raise voice for the voiceless.

The change in political environment in West Bengal, from a 34-year Leftist rule, has fuelled the rise of more productions in this genre. And now, with the rise in right-wing politics in the state, theatricians believe there are more reasons to worry.

Pre-Independence era

The history of modern political theatre in India can be traced back to the pre-Independence era when it was perceived as a major tool of propagating nationalistic ideas. However, it has long been used as a means of protest against injustice and oppression.

Writer Pushpa Sundar in her article Protest through theatre — The Indian experience, says that theatre was revived in India only after the British established its rule firmly in 1818.

“Used initially only to entertain, it later became a vehicle of protest against the political domination of the British and the social ills of the society,” she writes.

In Bengal, what could be regarded as one of the first political theatres would be Neel Dorpon, written by Dinabandhu Mitra, and concerned the exploitation of indigo farmers by the British. Reverend James Long, who published a translation of the drama, was in 1861 tried for libel before the Calcutta Supreme Court.

How the performances of Neel Dorpon and other similar plays across the state in 19th century prompted the authorities to push for suppression of a rising nationalistic feeling in performance art would itself be a vast topic to discuss. Nonetheless, what ensued was the arrest of actors and a law later that aimed at preventing dramatic performances which were seditious in nature.

In the mid-20th century, a rise in Marxist and anti-Fascist sentiments among the oppressed middle class led to a revival of political and protest theatre in India. It was during this time that the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) was formed and over time, found relevance with the urban as well as rural masses. Among its prominent members were Balraj Sahni, Prithviraj Kapoor, Ritwick Ghatak, Utpal Dutt and several others.

“Political theatre became popular during World War I but during the eighties some people started playing safe. More ‘art for art sake’ plays were produced during that time,” says popular thespian Sridip Chattopadhyay. However, a few groups kept on and plays like Lal Ghase Nil Ghoda were staged, he says.

Legacy of Badal Sarkar and others

Sudhindra Sarkar, popularly known as Badal Sarkar, remains a benchmark for people’s theatre not only in West Bengal but across the country. He has been the epitome of third theatre in the country whose plays have been translated by theatre greats such as Amol Palekar in Marathi and Girish Karnad in Kannada.

Third theatre, to Sarkar, is a form that is different from the first that is the traditional folk theatre, and the second, the urbanised and westernised one. It discards the conception of elitist entertainment and focuses on the creative expression of a human body to highlight socio-political issues.

Recipient of Padma Shri and Sangeet Natak Academy Award, Sarkar popularised third theatre, a new theatre movement, with his anti-establishment plays during the Naxalite movement in the 70s. He aimed at creating a new theatrical language, one that breaks the conventional notions and looks beyond the restrictions set by the state.

For instance, in one of his most iconic plays, Michhil, Khoka speaks to the audience of his suffering, but remains invisible for most part of the play, while the drama keeps showing scenes from the daily life, of funerals, communal tensions and more. No one lends an ear to Khoka, his suffering remains unacknowledged throughout the play.

It appeals to the audience, in the strongest unspoken words, to reconsider their role as responsible citizens of a civilised society. From a technical perspective too, the play needs no special infrastructure and can be staged as a nukkad natak (street play). Also the props, if at all anything is used, are common household items that can be found easily.

Among other playwrights whose theatre contributed to the rich heritage of political theatre were Girish Chandra Ghose and Utpal Dutt. Ghose (1844-1912), who was manager of the Great National Theatre of Calcutta, wrote on issues of socio-political significance and was one of the leading dramatists of his time. His plays, Siraj-ud-daula and Mir Qasim, were banned under the Dramatic Performances Control Act for their “explicit” content about the emergence of the British rule in Bengal.

Utpal Dutt is one of the biggest names in Leftist political theatre and was arrested at least twice due to his extremist views. He was not reluctant to voice his political ideologies through his work and the same was seen in three of this plays written during the Emergency period — Barricade, Dushwapner Nagari and Ebar Rajar Pala. Dutt had also staged a play on religious fundamentalism titled Janatar Afim in 1991, a year prior to the demolition of Babri mosque in Ayodhya.

Was theatre ever apolitical?

The answer is no, thespians believe. Theatre was never apolitical, says Chattopadhyay, who is associated with the theatre group ‘Akto’. Directly or indirectly, he says, politics has been a major component of theatre.

Other dramatists too agree. For Md Selim, a theatre practitioner who works with the group ‘Swapnochar’ in North 24 Paragana’s Gobardanga town, theatre or art in general cannot exist without politics.

But what all is political?

Political theatre is an umbrella term for all kinds of theatre that does not exist for the sole purpose of entertaining. It seeks to give a message to the audience. In a modern environment, it has adapted itself to become widely accessible to the masses and diminish the urban-rural divide.

Selim says political theatre doesn’t mean just calling out the good party from the bad. “It’s not like as if a performance will conclude that the BJP is good, or the TMC, or any other party. The significance of political theatre lies far beyond these party-based politics,” he adds.

For instance, Selim cites the popular Bengali fable Raja o Tuntuni, which narrates the story of a king and a bird living in his premises, to draw a comparison between the ruler and the ruled, and the relationship between these, to refer to two different classes.

“Showcasing politics through such simple and easy-to-understand topics is the essence of political theatre for the masses. Such performances may not make use of politics-oriented phrases to agitate people, but could silently convey a message,” he says.

He also stressed on the aspect of mobility of theatre for it to be accessible to the masses. “This is why my performances are always based on a free form, where light, sound and stage are not a necessary component.”

Panchali Kar, who is associated with the theatre group ‘Samuho’, says theatre is not possible without politics. “Not just mainstream political theatres, even feminist and queer theatres are political in nature,” she adds. “For me, all plays by Badal Sarkar were political. Some may not be about parliamentary politics, but they were essentially political. Even Rabindranath Tagore’s works were political, be it Chandalika, Chitrangada or Raktakarabi.”

But the times, they are a changin’

In the last one decade, West Bengal has witnessed the rise of not one, but two political powers. In 2011, Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress defeated the Left front and formed the government, resulting in a change that affected political theatre in the state.

On the difficulties faced by theatre practitioners under the new regime, Chattopadhyay says, “After 2011, we saw a big change. It’s not that the previous Left rule was any better, but TMC government was not the right substitute for it. We spoke against the authorities before and we did the same even after the change in the government. After this change, more political theatres started coming up in the city and many of them were not affiliated with any party and remained independent.”

One of the major issues that these theatre groups faced, he claims, was that they did not receive government funds if they spoke against the government of the day. “But some people did question those in power even after receiving grants. Money doesn’t belong to them, it’s public money,” Chattopadhyay says.

Analysing the current situation that indicates a potential saffron wave in the state, he also expressed concern saying, “If they become the principal opposition in the state, we will start getting more threats.” However, on a positive note, he adds that more productions of political dramas are being done in Kolkata.

Kar agrees with Chattopadhyay. “The current situation is making it difficult for political dramas but productions are still on across the city. This is why we don’t take grants from the government,” she says.

The difficulties, as we speak, can be better understood in simple terms through an incident that Selim narrates. He recalls a play he was a part of and was supported by local authorities.

“At a railway station, a ruling party worker, much younger than me, calls me and asks whether the play says anything about the chief minister. ‘Didir byapare kichu nei toh?’ I was shocked to hear that. Imagine an artiste being pulled up in the public and interrogated,” says Selim. Such is the embarrassment, he claims.

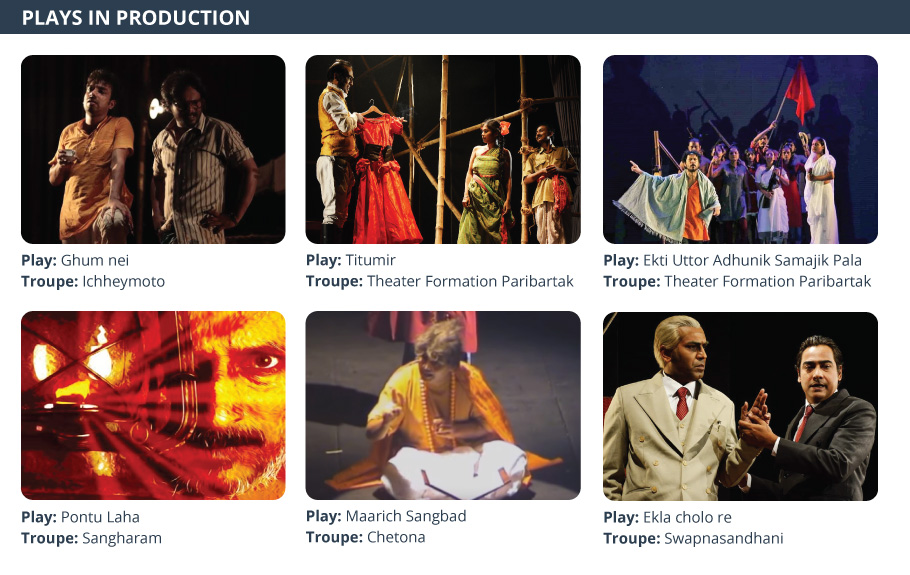

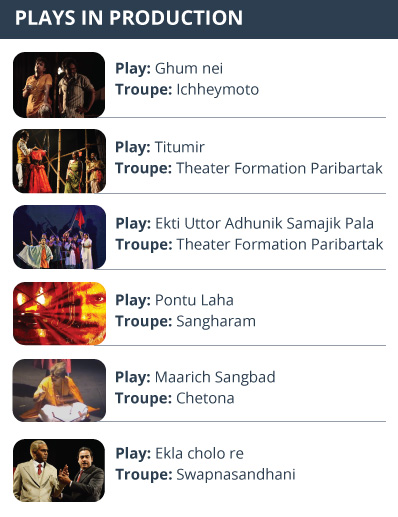

Some of the political dramas that are in production now in Kolkata are Ghum nei, Titumir, Ekla cholo re, Shekol chera haater khoje and Ekti Uttor Adhunik Samajik Pala, says Kar.

Titumir, being produced by the Theater Formation Paribartak group, is about a peasant leader who tries to fight against oppression by treacherous zamindars and the Britishers. Set in the backdrop of the British Raj in 19th century, the drama encompasses politicisation of religion and usage of sectarian politics, and draws a relevance to the current times. The original play was earlier written by Utpal Dutt. Another play by Theater Formation Paribartak, Ekti Uttor Adhunik Samajik Pala, is an absurdist, Pythonesque political satire that critiques every political avenue.

Political theatre and contemporary audience

Theatre in erstwhile Calcutta was mostly an urbanised one until the emergence of the pre-Independence protest movements. But as it picked up sentiments of nationalism and widened its scope to erase the rural-urban divide, it gained mass acceptance.

However, with the emergence of popular mode of communication, such as the television and the cinema, theatres took a hit.

“Theatre is a strong medium of communication. But after television and cinema arrived, it has somewhat lost its respect among the newer generations. They lack an understanding of political dramas. What’s the point of performing a piece with political overtones if the audience doesn’t understand? At times, I have experienced, they also treat street theatre in a disrespectful way,” says Selim.

He says that to make street theatre, especially political or third theatre, more successful, it needs mass participation. “Also, the artistes need financial assurance; even they need to survive.” He further says that there has been a fall in audience, not by numbers, but as per their thought process.

“Earlier, there used to be one-act drama competitions in rural Bengal. There, the participants focussed on receiving more cheers from the audience — something that even the judges used to take into account while deciding the results. This exact mentality pertains to being audience-oriented, which has been dangerous for any form of art. Art is meant to convey the philosophies of the artist, and its market-oriented functioning is ruining its essence,” he says.