- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Our identity, legacy at stake in India-China face-off: Galwan family

For the Galwan family, the contested valley is at the core of their happiness and prosperity. They fear that if China won’t retreat from Galwan Valley, India may lose a strategic location and territory but the Galwans would lose the fulcrum of their existence, legacy and dreams.

“He was a celebrity of his times in Ladakh. Whosoever visited Ladakh from undivided India, China, Tibet or Afghanistan during the period (1890-1925), would want Ghulam Rasool Galwan to be their pointsman, and a record-keeper too,” Ghulam Nabi Galwan, his grandson, tells The Federal. Tales and legends of the famed 19th century Ladakhi explorer-guide have been revived by the recent...

“He was a celebrity of his times in Ladakh. Whosoever visited Ladakh from undivided India, China, Tibet or Afghanistan during the period (1890-1925), would want Ghulam Rasool Galwan to be their pointsman, and a record-keeper too,” Ghulam Nabi Galwan, his grandson, tells The Federal.

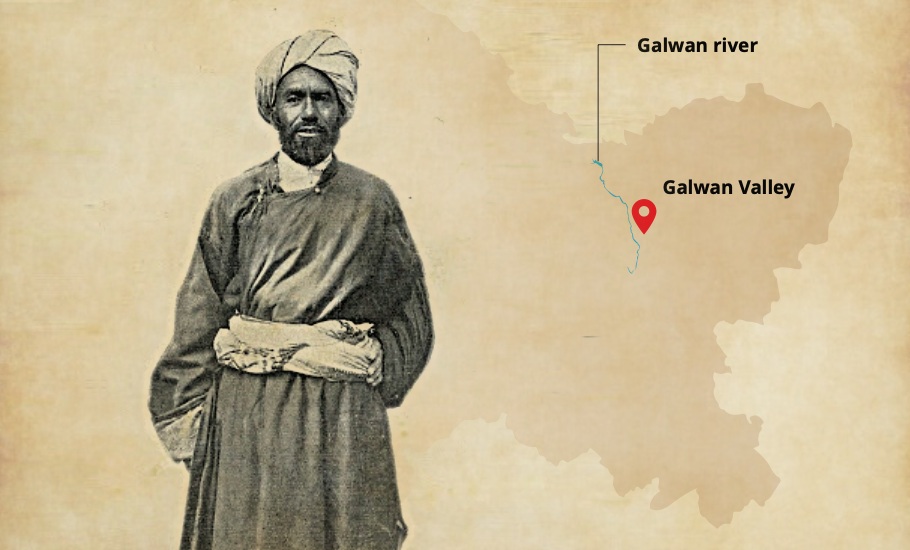

Tales and legends of the famed 19th century Ladakhi explorer-guide have been revived by the recent clashes between Indian and Chinese troops in Ladakh’s Galwan Valley, a treacherous icy terrain at 14,000 ft altitude where 20 Indian soldiers lost their lives.

“The place where our grandfather saved lives of 20 people, has now witnessed bloodbath of 20 soldiers. It reminded us of 1962 (India-China war),” says Ghulam Nabi.

The strategic key

The clash re-asserted the strategic importance of these freezing heights at the cusp of central Asia and south Asia.

It also brought to focus the Galwan clan of Ladakh and descendants of this great scout, whose necessity to earn money became a passion and landed him at the centre of several political adventures, diplomatic missions and spy stories, which defined the history of this mountainous region and its neighbours.

Around 95 years after his death in 1925, the family members are now at the centre of discussions around Ladakh. The family’s oral narrations about the Valley that their famous ancestor discovered also serves as a potent tool for the media and indirectly for the government to assert that the Galwan was part of Ladakh in India and not a Chinese territory.

The battle for Galwan Valley is more personal for the clan. It is about their identity, survival and legacy. The Valley remains at the root of their existence. In fact, many journalists currently stationed in Leh to cover the tensions between China and India are staying in a hotel owned by one of the descendants of Galwan.

Sixty-year-old Ghulam Nabi Galwan, son of Habibullah Galwan, the second son of Ghulam Rasool Galwan, recalls that for his grandfather, the Galwan river was at the centre of his life, and it changed the course of his whole clan.

The 80-kilometre-long river, an upstream tributary of Indus river, flows through a Valley in eastern Ladakh. Galwan passed the untrodden crests and troughs of this region and assisted many European explorers during scouting missions, at the turn of the 19th century. His eagerness to face challenges and survival tactics made him famous among Europeans, who were in awe of his raw courage and traditional expertise.

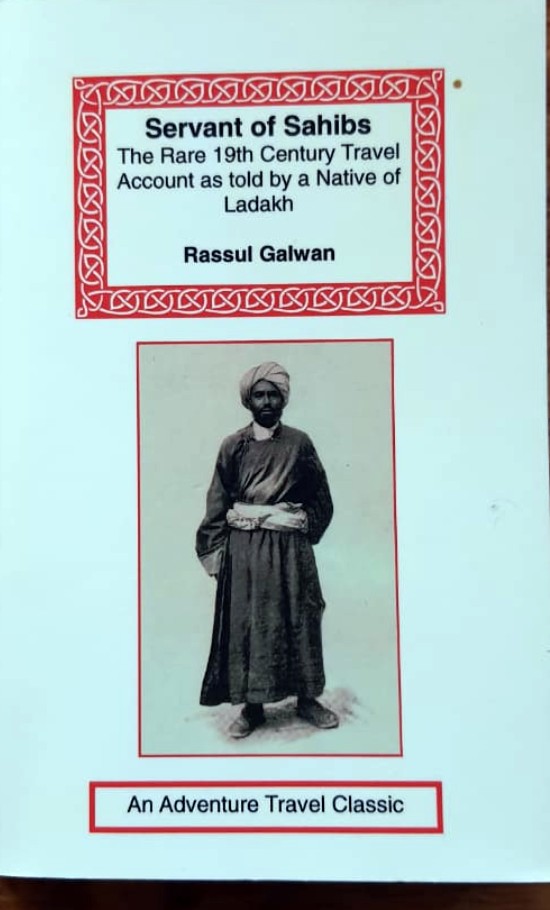

The adventures of Galwan are recorded in a book penned by him, Servant of Sahibs, in broken English. A British Army officer and explorer Francis Younghusband, who had taken Galwan on his expeditions in the Valley, wrote the foreword and published it as well.

The book was result of the legendary explorer’s interest in reading and writing. He would always maintain a tour diary. He used to send it to Robert Barret, an American adventurer, for correction and editing, as his English wasn’t good. “Later Younghusband printed his diary in its original form at Cambridge in 1920,” Ghulam Nabi says.

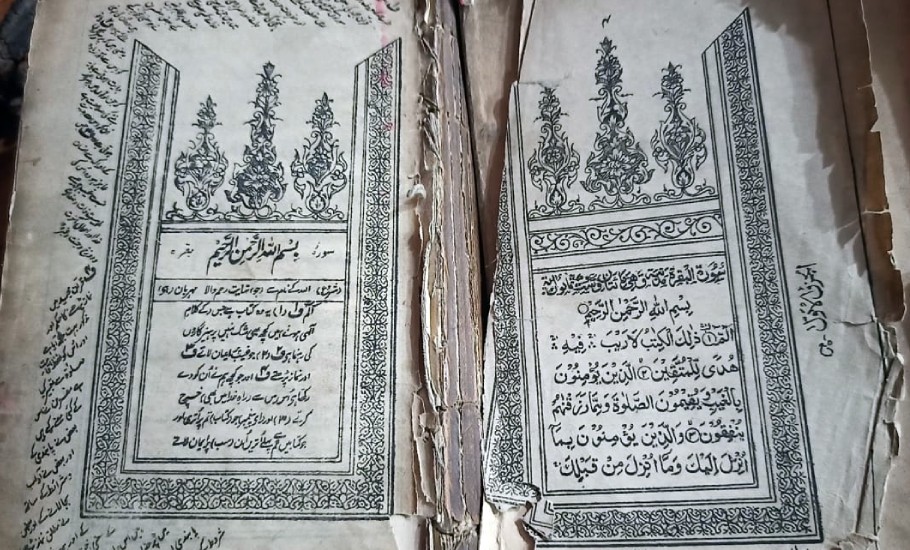

Galwan, with his exposure and interaction with the travellers had learnt six languages, including Turkish, Chinese, Tibetan, Kashmiri, and English.

He discovered the Galwan Valley at the age of 14 in 1892 when travelling with Charles Murray, the seventh Earl of Dunmore. Younghusband had referred Galwan to Murray, after his extensive expedition with him. The 20-something group of Lord Dunmore lost their way in bad weather and were stuck in a mountainous valley.

“Being the expedition team leader, the British officer ordered my grandfather to find a way out,” Galwan’s grandson says. “After walking for several miles, my grandfather found a river and a route ahead of it. When he informed the group about the new route, the group was extremely happy and Lord Dunmore named the valley and river after Galwan.”

Conqueror of the unconquerable

The adventures of Galwan took place in the shadow of the great game of the British Imperial Era, when both the British and Russians were competing to take control of Central Asia. The complexities of the great game between the then world powers were equally reflected in the deceptive terrain of the region, which Galwan not only traversed but conquered.

“It was all about inhospitable expeditions in difficult terrains of Karakoram ranges, into Tibet, Yarkand (now in Xinjiang China) and other central Asian regions like Afghanistan,” says Ghulam Nabi, a former finance officer of NGO, Leh Nutrition, funded by Save the Children and UNICEF.

Galwan’s group would trek into no man’s lands on ponies and camels at a time when any modern day trekking gear was even unheard of. The perseverance of travellers coupled with Galwan’s traditional intelligence and experience led them to destinations, which became landmarks in the history of several nations.

“It took them 40 days to reach Yarkand from Leh,” the grandson said. Travelling across the cold desert’s barren mountains, Galwan would always lead from the front on a Central Asian two-humped camel adaptive to extreme cold temperature. It was never an easy undertaking.

“Explorers would often run out of food and other essentials. Those rugged terrains and treacherous treks would devour animals whose bones would be found on those tracks next season,” recounts the grandson.

But as someone who had traversed those tracks as a master explorer, Rasool Galwan knew desperate measures for desperate times. He made sure that people travelling with him survive come what may.

A legend has it that during one such Himalayan tour led by Galwan, the group ran out of food. “In order to survive, the leather shoes were boiled and served,” he says. “It was my grandfather’s idea, which saved many lives then.”

Back home in England then, the British explorers would repeatedly give references of ‘the broken-English speaking Ladakhi explorer’ to their country’s travel enthusiasts.

“Once, a British woman named Mrs Little Dale wanted to meet Dalai Lama 13th in Lhasa. Galwan not only made her journey possible but made it a memorable experience for her,” Ghulam Nabi reminisces.

Central plot

The British officers, happy with Galwan’s hard work and honesty, gave him the title of Aksakal of Leh, or chief assistant of British India. In 1923, the British gave 12.5 acres (100 kanals) of land in Leh as a gift to Galwan.

Leh back then was a bustling trade centre for Central Asia, where people from India, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Tibet and Aksai Chin would trade in a barter system.

The happy moments Galwan shared with the travellers are reflected in the collection of souvenirs the family has preserved as memento of the successful but short life of their ancestor.

Even today, adventure-seeking foreigners often show up at the Galwan residence in Leh.

Some years back, Ghulam Nabi says a British traveller came enquiring about the progeny of Ghulam Rasool Galwan.

“He was surprised to see me,” he says. “Perhaps he had imagined that he would run into some superman, but seeing a commoner sitting on a chair sweetly surprised him. I don’t blame the curious soul. Such, I guess, is the legend of my grandfather that he continues to rule over imagination of masses.”

Despite living in Ladakh for decades, Ghulam Nabi says his father and many of their relatives have never visited the Galwan Valley. But the mere mention of it evokes emotions. The recent news of clashes has unsettled the whole family.

For the Galwan family, the contested valley is at the core of their happiness and prosperity. They fear that if China won’t retreat from Galwan Valley, India may lose a strategic location and territory but the Galwans would lose the fulcrum of their existence, legacy and dreams.

“Galwan Valley is the central plot in our family story. It is the skeleton, which made us what we are,” Ghulam Nabi said.

(The author is a Srinagar-based freelance journalist)