- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

On his birthday, let’s see the world through Ruskin Bond’s window

Sitting at an altitude of 7,000 ft, a tiny space has become home to India’s celebrated author Ruskin Bond who’s turning 86 today (May 19).

“To me as a writer, the mountains have been kind. They were kind from the beginning, when I left a job in Delhi and rented a small cottage on the outskirts of the hill station. Today, most hill-stations are rich men’s playgrounds, but twenty-five years ago, they were places where people of modest means would live quite cheaply.” – Ruskin Bond, Rain in the Mountains: Notes from...

“To me as a writer, the mountains have been kind. They were kind from the beginning, when I left a job in Delhi and rented a small cottage on the outskirts of the hill station. Today, most hill-stations are rich men’s playgrounds, but twenty-five years ago, they were places where people of modest means would live quite cheaply.”

– Ruskin Bond, Rain in the Mountains: Notes from the Himalayas

A small 6ft by 15ft room with big windows opens to the forests on its left, the hills of Mussoorie and its quaint lodges in the middle and, on days when the sky is clear, one can see the city of Dehradun at the far end on its right. The road beneath the windows leads to the town’s commercial hub in Landour, a cantonment area in the foothills of Garhwal range of Himalayas.

The maple trees, the Himalayan rhododendrons, the pine and walnut trees, the macaques, the wildflowers, the changing skyline, the clouds that encompass the surroundings offering misty views, changing every few seconds, are all part of the narrative he builds in his books.

The tourists and locals — fruit vendors, vegetable sellers, the kids playing outside his house, the postman, the bookseller, civic workers along the road beneath his windows, all form important characters in his books.

Sitting at an altitude of 7,000 ft, this tiny space has become home to India’s celebrated author Ruskin Bond who’s turning 86 today (May 19).

A room painted yellow, a single cot where he takes multiple siestas through the day, a chair, a table and a rack full of writing materials and books, an extra piece of spectacles, all placed opposite to the windows are the much-needed elements for his writings. He has been immersing himself into reading and writing from this space for four decades now. It is from this very room that he has won two of India’s highest civilian awards — Padma Shri (1999) and Padma Bhushan (2014) — for his contribution to the world of literature.

His home has become a tourist destination in Landour so much so that sometimes even honeymooners turn up at his door to seek blessings. He says he doesn’t entertain his readers at home as he prefers to live in tranquillity.

With nearly 150 titles—including children’s books, short story collections, poetries and memoirs, his books are engaging to all. His fictions and novels have also made it to the big screens such as Junoon by Shyam Benegal (1979), the Blue Umbrella (2005) and Seven Sins Forgiven (7 Khoon Maaf, 2011) by Vishal Bhardwaj.

He prefers to talk less and save much of his conversation for his readers and those invisible listeners on radio, with whom he strikes a congenial connect. A reasonably contented man, he calls himself a writer without regrets.

Here is a conversation with India’s most loved writer when the author of this piece had the opportunity to see the world from Ruskin Bond’s windows in 2017. Excerpts:

How important are these windows for you and how does the world look from here?

For writing and sleeping I’ll have to be near a window. It keeps you in touch with the world even if you are not a great traveller or a very social person (describing himself). You need a window on the world. And, the more you see from it, the better.

From that window, I see the sky above and the hills, the mountains and the front, the roads, people on them and the rubbish dump too. You can get to see everything—from the blind to the ridiculous.

You do get used to it (the views and the place) and that’s the danger being in one place for very long. And you take it for granted. I stopped admiring it in a way because it’s just become a part of my daily life.

The sky is constantly changing, the climate goes from very cold winter into mild summer and a lot of rain nowadays. And the autumn and the foliage is totally different.

How do you pick your characters?

Well, some are familiar people who we see regularly, like vendors, school children, labourers working on the road or it could be tourists of course.

How do you manage the slew of tourists/readers wanting to see you all time?

The tourists come banging on my door from time to time disturbing me. Like seeing waterfalls, they think seeing the local author is part of their tour agenda. And that can be irritating and it turns up at odd times—early morning or in the afternoon when I am sleeping, without warning actually. I do see people. But it’s better if I know when they are coming. Otherwise it can be bothersome.

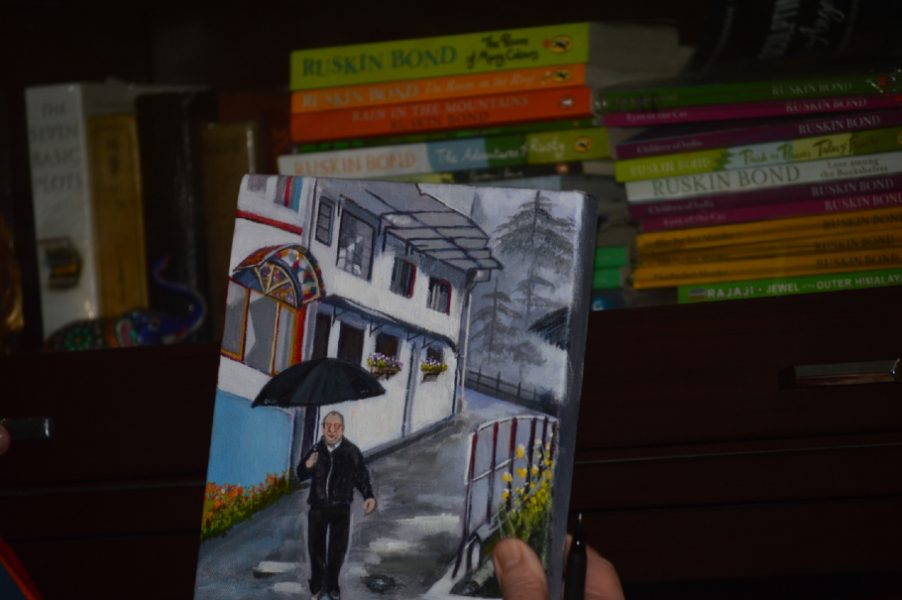

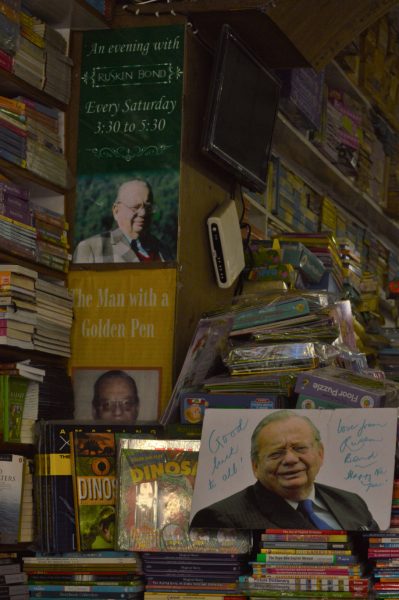

Sometimes, they (the Cambridge Book store in Landour) disturb me because they’ll expect me at the book shop for a reading session on Saturdays. I usually go there and sign some books. And there I am quite happy to meet visitors, tourists, readers, and chat to them because they are passing through and they are not putting any pressure on me.

It’s nice for an author to have people coming and wanting him to sign their books and talk to them. It’s better than not being noticed at all. But sometimes it gets a bit too much.

How has Mussoorie/Landour, which you describe in your books very often, changed over the years?

Be it Shimla in Himachal Pradesh, Mussoorie in Uttarakhand, Darjeeling in West Bengal, hill stations have changed a lot over the years. In the 1950s and ’60s when I came to live here, businesses were bad. The Indian middle class had not yet discovered hill stations. Only Anglo-Indians, Europeans and Britishers used to flock to the place.

But from the ’70s onwards, the middle class became quite affluent and hill stations became popular and caught on. Most of the towns like Mussoorie are not equipped to handle the crowd. Too many people and too much traffic as everyone now has, if not one, two or three cars at home and they come from Delhi or other nearby towns. And you can’t escape from the noise. It’s hard to find a quiet spot anymore.

It’s become a weekend place because people now no longer have time for long holidays but they can easily drive up from Delhi or even fly from places like Bombay, Bangalore and Chennai, for short holidays. It’s good for the hill station’s economy.

When I came to live in Mussoorie in 1963-64, there were three cars in town. Two were owned by the doctors and one by a school. Now there are about 1,000 taxis and a few thousand cars and motorcycles of all kinds. It’s become a problem in a way.

Mussoorie has advantages — it’s convenient and close to Delhi — compared to other stations like Shimla and Nainital. Which is one reason why I came and settled back in the ’60s.

Although I wanted to be in the hills and away from the daily rat race, I didn’t want to be cut off totally, because I still wanted to be able to go and drop in on a publisher or newspaper office or an editor in Delhi. And gradually all the publishers have moved to Delhi over the last 30 years or so.

Is there something that you yearn to do at your age and are not able to?

Not too many things, you know, I’m a reasonably contented man because I’ve never wanted too much out of life. The thing I miss of course is a garden at home.

I would like to have a nice garden where I can grow lots of flowers and different plants for which you need some space on the ground. Here, I am in a flat actually without any garden space. I know a lot about plants and flowers, especially the wild flowers. When I used to go for walks, I would sort of study them.

The only time I really had a garden was when I was very small and my grandmother had a bungalow with a nice garden in Dehradun. So, I often sort of picture that in my mind. I don’t think I’m going to have that garden ever.

But by and large, you can say I am ‘a writer without regrets’.

It took many years to get established. But the very fact that I did in the end and that too in India where freelancing was very difficult for anyone in the 1950s, ’60s and even ’70s. It was not easy for writers here. But it’s much better now. Many writers now actually make fairly good money out of their books. That wasn’t the case always.

You penned your autobiography. Is there anything or anyone close to your heart that you missed mentioning in your book/s? Would you like to share with us?

Oh, yes. So many things in fact. Relationships basically. I always remember (after finishing the book) and say oh I should have written about that old friend, or someone you loved and valued where you sort of felt it’s over and done with long ago, but maybe I could have dwelt on it more.

I think maybe because I was so close to my father that I might have been a little unfair to my mother, who for reasons of her own led a life that didn’t suit me in a way as her son. So you sometimes have a few regrets like that.

You can never really write a complete autobiography. Although I’ve tried my best to be honest with myself and with the reader. It’s only human I think to hold back occasionally. Nobody ever tells the full truth about himself/herself.

How have you overcome technology changes over the years?

Technology hasn’t affected me at all. We’ve got this old landline which never works. And even when it does work, I do take it off the hook (laughs). So Rakesh (adopted grandson) has bought a mobile phone, and his sons and daughters are all equipped with laptops and latest cellphones.

Very rarely I read on computers. But I used to read (book reviews) more in the newspapers and magazines. But here, there’s no one to even deliver a newspaper. So, I don’t even get one. I keep up with the television news in the evening.

I get some very nice letters from readers. Sometimes handwritten. Young readers take the trouble of writing by hand knowing that I don’t use anything (computer or mobile phones). Unfortunately, I can’t reply to all of these because if I get about a dozen letters a week, it’s hard to sit down and just be doing correspondence all the time. Then I wouldn’t be doing my own writing that way.

Sometimes they write about being unhappy. Maybe they feel I am a nice elderly uncle or grandfather figure to give them some advice or comfort.

Sometimes honeymooners turn up at my doors and want my blessings. I don’t know why (from me) because I never married anyway. And as far as I can recall, my parents were quarreling most of the time. So, I don’t know if I’m the right person to give them blessings.

Tell us about your school life?

If I look back on my school days… we had a good library. And we were told to read books within a general class of 30 boys in boarding school. There were just two or three of us who actually use that library.

In those days, we had none of the things that we have now (tech gadgets) as diversions. There was no television, no internet, no video games and all these things. So even though readers were a minority, and they’re still a minority, it has grown in some ways with the spread of education and more and more schools.

So, even if only 2% (of the population) are reading, it’s actually far more than it was 50 years ago. Which is why books are actually selling and publishers are doing well.

In school, we all read comics, and went to the cinema once a month and that was it. You didn’t have the variety of entertainment you have now.

When was the last time you went to a cinema?

I used to go to the cinema two-three times a week as a young boy in Delhi or London. I was a great movie buff. But the last time I went was to a film festival in Goa about 10 years back when Vishal Bhardwaj had premiered The Blue Umbrella which was based on a story of mine. Through the 1940s-60s I was a terrific moviegoer.

But I’d prefer reading now. If I have a choice of what to do in the evening, and if I have a good book to read, that would be my first choice.

Tell us about your reading choices…

I like reading old favorites, biographies, history books, and not too much fiction. But crime and detective novels I enjoy reading now and then. I’ve always been a good reader and I always look out for old books which are hard to find.

In fact, there was a bookshop in Bangalore, Select Bookshop on Brigade Road, from where the owner sometimes sends me handwritten lists of old books that he’s picked up. And they send them through posts.

I mentioned him in my last book, Confessions of a Book Lover, in which I talked about favorite books and how I discovered them and when and what I was doing at the time. It’s a book about books.

What’s your daily routine like?

It’s fairly routine, except when I go out occasionally. Now with all these lit fests happening all over the place, sometimes I’m dragged around to them, though I am not particularly fond of them. But publishers, you know, sometimes make me go.

Rakesh or his wife brings me a cup of tea at 7.30- 8 o’clock when I’m in bed. That’s the best time to write. Before breakfast I’m reasonably fresh and not getting much in the way of disturbance. So for about an hour, I write before breakfast and maybe a little after.

But I get a bit drowsy around noon and take a pre-lunch nap. After lunch, I need another siesta to recover from the earlier siesta, so I take an afternoon siesta (laughs).

Then I might do some reading in the afternoon or in the evening. I used to go for walks. But now I have a bit of a knee problem. I go for walks but not very far.

And in the evening I sit with the family or whoever’s here. Like yesterday, one of my publishers, Ravi Singh (of Speaking Tree) turned up, the one who’s published the autobiography. We sat down and had a couple of drinks till 11pm and discussed future books and projects.

So it varies. No fixed routine?

I am a lazy chap. (Not so lazy as he says. In 2017, when this interview was done, Bond had already written three books—Confessions of a Book Lover, Looking for the Rainbow, and his autobiography, Notes from a Small Room. Besides, he also wrote a poetry book and a children’s book.)

There’s always something to write. I am a habitual writer and I don’t get writer’s block.