- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

NRC: Once bitten, twice shy – Hindu immigrants in West Bengal

A sense of anxiety and déjà vu hung like a dark cloud over Cooper’s Camp, one of the oldest refugee settlements in India. Hunched over a rickety table on the verandah of a small brick house, overlooking the marshland, stretching east towards the 2,216-km Bangladesh border, Ashok Chakraborty was busy rummaging through old documents. A paltry group of people that had gathered in his...

A sense of anxiety and déjà vu hung like a dark cloud over Cooper’s Camp, one of the oldest refugee settlements in India.

Hunched over a rickety table on the verandah of a small brick house, overlooking the marshland, stretching east towards the 2,216-km Bangladesh border, Ashok Chakraborty was busy rummaging through old documents.

A paltry group of people that had gathered in his house looked equally fretful. Rising from a bundle of old files and pale papers, Chakraborty, the general secretary of the refugee council, said most of them — he was pointing towards the crowd — had lost refugee cards issued to their families.

“Until now, they did not feel those old pieces of papers, issued to their parents decades ago, will be so vital for their identity. I am of not much help to them either as many old files in our office here too have been lost. We have had to shift base several times,” he rued.

Technically, though a refugee camp, the fence that once surrounded it has long gone and Cooper’s Camp over the years has grown into a town, sprawling over 200 hectares, in West Bengal’s Nadia district.

Established in March 1950 in what was a military base during World War II, Cooper’s Camp is today home to over 20,000 people and has its own markets, medical clinics and schools. Most of the residents, including women, are menial workers.

Each resident here traced back their lineage to those who escaped the bloodbath in erstwhile East Pakistan to settle in this part of Bengal amid the horror of British India’s Partition in 1947.

“I was eight when my parents were forced to leave behind their house, land and livelihood to make a new beginning from the debris of deaths. Initially, we put up in Bangaon (now in North 24 Parganas district), and then shifted here,” recalled Chakraborty.

The albatross of NRC

Tales of Partition and flight of their parents and grandparents to India have been part of every household’s family lore here.

Sanjib Sarkar, 30, was not even born when the great exodus — the largest ever human displacement in recorded history — took place at the stroke of midnight on August 14, 1947, uprooting about 10 million people. But he could narrate the trials and tribulations of his grandparents as if it had happened before his eyes. Well, he grew up listening to them, he said.

“My grandparents came here as refugees in 1948 from Dhaka after their house was burnt down and land was forcefully captured. My grandmother used to narrate the traumatic tale to us. They sailed to India on a cramped boat in the darkness of night,” he recounted.

Listening to those stories, Sanjib had never imagined that seven decades later, the same horror of displacement would come back to haunt him and others in Cooper’s Camp.

“Panic has gripped people here after they came to know that names of mostly Hindu refugees were dropped from the updated National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam,” said Pintu Dutta, a local councillor.

Failing to retrieve any relevant document — even after rummaging through tucked away old family materials — that would prove his parents had migrated to India in 1950, Amar Halder had come to the refugee council’s office hoping to find any relevant piece of paper that would establish his Indian identity.

Soon after its establishment, the camp was divided into several blocks and each resident was enlisted in the relief office and registered in the “Ranaghat transit centre records”. After this classification, the displaced were allocated a hut each but they were not given bhoomi pattas or land deeds.

“In the absence of land deeds and identity documents of my late parents, how will I prove my Indian citizenship,” asked Halder, articulating an apprehension that is gnawing in the mind of every resident in this refugee settlement and elsewhere in West Bengal.

Assam vs Bengal

Since the issue of illegal migrants has never been a hot topic in West Bengal until recently, not many people had bothered to preserve the identity documents of their parents long dead.

Even government officials admit they aren’t sure if they have the electoral rolls of all the elections held in the state since 1952, making the prospect of an NRC in West Bengal more complicated.

“Even I won’t be able to produce identity documents of my late parents. Many will not be able to do so,” West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee had said recently.

Moreover, it is also not clear what would be the basis for the NRC in West Bengal and what would be the cut-off date to determine citizenship.

In Assam, the NRC was updated with March 25, 1971 as the base time to determine citizenship as agreed upon in the Assam Accord signed in 1985 to cap a seven-year long anti-foreigners agitation in the state.

Nevertheless, much like it happened in Assam, the fear swirling around the NRC has turned into a mass frenzy across West Bengal, as has been evident from eight suicides so far linked to the contentious proposition.

Nibhas Sarkar, committed suicide on October 4 in Ranaghat allegedly over the NRC issue, though his family denied it. Sarkar, an RSS functionary, had caught the imagination of BJP supporters in the state by actively campaigning for the saffron party’s Ranaghat Lok Sabha candidate in 2019 general elections, dressed as Hanuman. His neighbours, however, told the local media that Sarkar, who was himself a migrant from Bangladesh, was concerned over the NRC development in Assam, where names of many Hindus were excluded from the citizenship list.

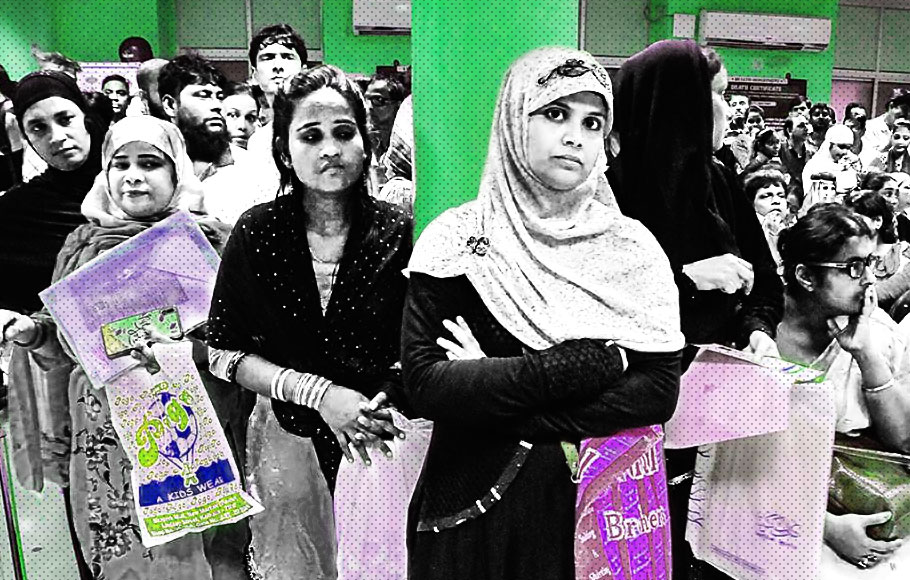

Amid fears that NRC could be implemented in West Bengal anytime soon, thousands of people, both Hindus and Muslims, had been queuing up regularly at government and municipal offices across the state, until the Durga Puja holidays began, for necessary documents.

This hard-pressed the state government to issue advertisements and video messages of Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, asking people not to be panicked by “NRC rumours”.

“There will be no NRC in Bengal,” the CM assured. But not many are convinced.

“How can we be so certain when Union Home Minister Amit Shah has been repeatedly talking about conducting NRC throughout the country,” said Tapas Debnath, who runs an eatery near New Cooch Behar railway station.

Interestingly, Debnath had voted for the BJP in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

BJP in tight spot over NRC

This fear over NRC among Hindu Bengali migrants, particularly those belonging to the Namasudra-Matua community, is increasingly becoming an Achilles heel for the BJP — something that many within the saffron party’s state unit admit in private.

The 2.87-crore strong community had overwhelmingly voted in favour of the BJP in the last general elections, helping the Hindu right-wing party to win 18 out of the state’s 42 Lok Sabha seats.

At least in seven seats — Cooch Behar, Alipurduars, Jalpaiguri, Maldaha North, Ranaghat, Bangaon and Bishnupur, the BJP’s victory was attributed to this scheduled caste community’s support.

It was then perceived that the NRC was primarily aimed at “weeding out” illegal Bengali Muslim migrants from Bangladesh as claimed by the Hindutva outfits.

What added to the BJP’s headache is the fact that most of the alleged NRC-related suicide victims in the state are from this community. They are in majority in 77 Assembly constituencies, out of 295 (294 elected + 1 nominated). The community also plays a vital role in deciding the fate of 21 other seats.

“There is no denying that our community had backed the BJP in the Lok Sabha elections. But the NRC results in Assam had come as a big shocker. As per some estimates, over 10 lakh Hindu Bengalis are on the verge of losing their Indian citizenship,” said Mukul Bairagya, a founding member of All India Namasudra Bikash Parishad.

He claimed that the BJP would be committing hara-kiri if it persisted with its NRC agenda in Bengal. “We are now holding village-to-village meeting to make people aware of the dangerous ploy of the NRC to make Bengalis homeless in their own state,” Bairagya told The Federal.

- The Citizenship Act of 1955 granted citizenship to every person born in India on or after January 26, 1950

- Diluting this provision, the Citizenship(Amendment) Act, 1986, provided citizenship by birth only if either parent was a citizen

- The Citizenship Amendment Act of 2003 restricted citizenship by birth only if both parents are citizens of India; or when one of the parents is a citizen and the other is not an illegal migrant

- The Citizenship (amendment) Bill, 2016 seeks to stipulate that Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afganistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh should not be considered illegal migrants

- Northeastern states are against the bill as they fear it will encourage Bangladeshi minorities to migrate to these states, eventually changing their demographic profile

- Many Bengali organisations such as All India Namasudra Bikash Parishad have opposed the bill, saying it does not specify the actual process by which illegal migrants will be eligible for Indian citizenship. The process is fraught with contradictions and will not help the cause of those excluded from the NRC list

- Moreover, these organisations argue, that after acquiring Indian citizenship — holding voter cards, passports and other citizenship documents — why should the citizenship of the Bengalis be put to NRC test again

The All India Bengali Organisation (AIBO), too has upped its ante against the BJP. “We are contemplating to hold a dharna in front of the BJP’s and the RSS’s state headquarters in Bengal to protest against the party’s anti-Bengali stand on NRC,” said Manas Roy, the national general secretary of the organisation.

To allay the fears of Bengali Hindu migrants, Shah during his visit to Kolkata on October 2 had asked the party’s state functionaries to reach out to the people with the assurance that no Hindu refugees would be targeted.

“The NRC would be done in Bengal only after the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) is passed,” he told party leaders and workers at Netaji Indoor Stadium.

The BJP is now trying to hard-sell the CAB as a protective shield for the Hindu Bengali migrants. But neither Bairagya nor Roy is convinced.

They argued, almost in unison, that if the BJP was so concerned about the Hindu Bengalis, why didn’t it declare this during its proposed NRC drive across the country — that no Hindu would be required to produce any archaic legacy documents to prove their Indian citizenship.