- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Nobody home! What Kerala’s ghost houses whisper about migratory trends

Forty-seven-year-old Krishnakumar P, from Athekkad in Trissur, has been working in the sales department of a multinational company at Philadelphia in the US for the last 15 years. His wife, a paramedic by profession, also works there. The couple’s two children are US citizens by birth. Well-settled in a faraway land, living the quintessential American dream, the family has no intention...

Forty-seven-year-old Krishnakumar P, from Athekkad in Trissur, has been working in the sales department of a multinational company at Philadelphia in the US for the last 15 years. His wife, a paramedic by profession, also works there. The couple’s two children are US citizens by birth. Well-settled in a faraway land, living the quintessential American dream, the family has no intention of returning to Kerala. Yet what awaits them back in Athekkad are relatives, friends and an empty house – standing two-storey tall, spread over 3,600 square feet built up area.

The house stays locked for most part, except for when a distant relative, who is paid a monthly salary, checks on it to ensure it is not illegally occupied or falls into ruins due to a lack of repair.

A drive across the state brings one across umpteen such houses, whose doors and windows have not been opened for years for fresh air to enter, and which are guarded by sturdy locks. The occasional visitors of these houses, owned by NRIs, are local caretakers.

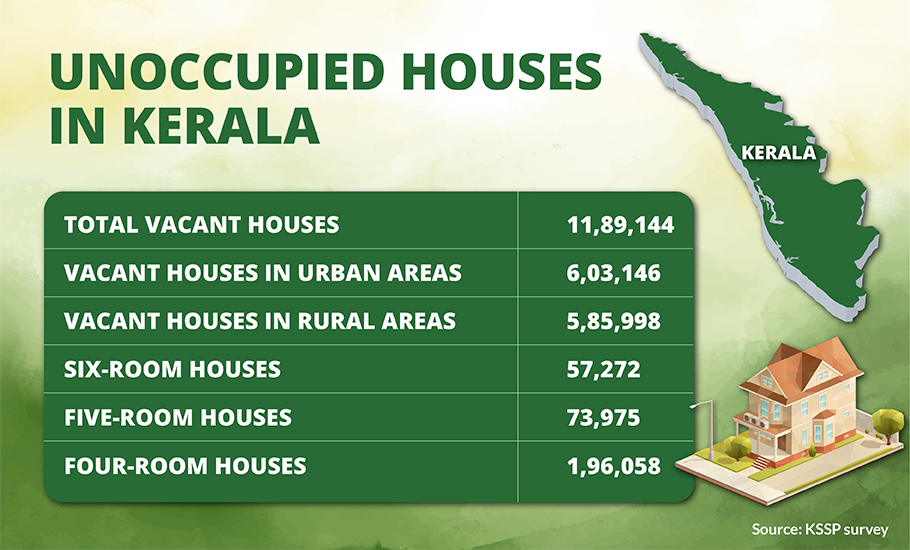

There are 11,89,144 vacant homes in Kerala, according to a 2017 survey by the Kerala Sastrasahitya Parishath (KSSP), which the organisation claims is based on data from the 2011 census. A total of 6,03,146 vacant homes are in urban areas, while 5,85,998 are in rural areas. The report also notes that there are 57,272 vacant homes in Kerala that have more than six rooms. As many as 1,96,058 vacant houses have four rooms, compared to 73,975 vacant homes with five rooms. While the main concern of KSSP was the environmental impact of too much construction in the state, they have also called for extra homes to be distributed to the homeless.

According to the report, “If all the extra houses are distributed to the people who don’t have a house, it would be a great revolutionary policy after the land reformation movement.”

As per the data available with the local self governments, there were around 18 lakh houses that are vacant and locked in the state in 2022.

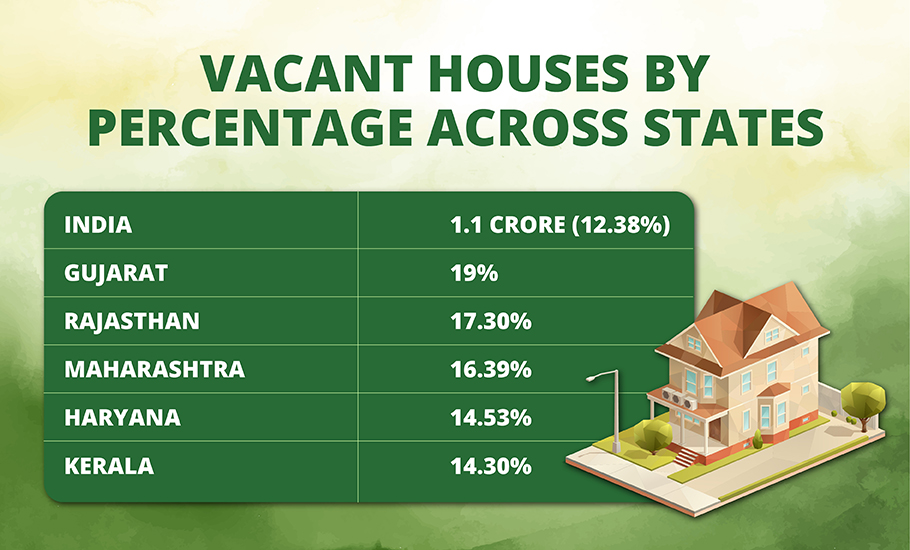

In terms of the percentage of vacant homes, Kerala is ranked fifth. Gujarat has the highest percentage of vacant homes to the total number of homes, at 19 per cent. Rajasthan (17.3) and Maharashtra are the next state after the state (16.39). There are currently about 1.1 crore vacant homes across the nation. As a percentage of all houses, this equals 12.38 per cent.

As a way to arrest the rising trend of leaving houses unoccupied and ensure the exchequer doesn’t suffer revenue loss due to houses being left vacant, the Kerala government decided to hike the tax.

In the budget for 2023-24, the government of Kerala announced an additional tax on vacant houses in the state. “A proper method of taxation of multiple ownership of houses by a single individual and newly constructed unused houses will also be taken up. A comprehensive revision of these will be taken up by the Local Self Government Department. If these measures are implemented, at least [Rs] 1,000 crore is expected as additional Own Fund of Local Bodies, which can be productively used,” said finance minister KN Balagopal in his budget speech.

“The fact is that many houses that are vacant do not pay even the regular building and property taxes because nobody is home to make the payment. This may not be deliberate. So, the government is planning to make arrangements for online notification and payment of taxes, as a starter. If there are defaulters even after that, we will think of denying services like electricity and water to these properties. For this, we may need amendments in rules,” LSG minister MB Rajesh told The Federal.

“There is a logic behind the additional tax. These houses are built using the resources of the state. So, they are bound to pay some kind of tax. Not all vacant houses are owned by expats, many people have more than one house and so they too are left unoccupied,” explained Rajesh. The minister is well aware of the complicated nature of the budget proposal. “First of all, we will have to define vacant homes according to the period of vacancy. As of now, priority will be given to collect the tax arrears. The implementation of new tax will be done only after detailed consultations,” added the minister.

“Migration is one of the main factors behind the closure of houses in Kerala,” said S Irudayarajan, the chair of International Institute of Migration Studies and Development, Thiruvananthapuram.

“It is the aspiration of every Malayali to build a house in their own village. They spend their life’s savings on it. The Keralites who migrated to the Gulf region in 1960s and 1970s contributed to the majority of concrete houses in the state. These days many of them move out of the Gulf region to western countries. For instance, according to one of our surveys, 30 per cent of the Keralites in Toronto, Canada had lived in some Gulf country at some time,” he said.

“During the Gulf migration period, people were always thinking of coming back to Kerala and that’s why they constructed these houses. There was no scope for permanent residency in those countries. However, their children who migrate to other countries like the UK, Canada, Australia, or New Zealand, do not want to come back. This is a new trend which could have long lasting impact,” Irudayarajan told The Federal.

According to a recent study conducted by Sulaiman KM and Bhagat RB with a sample size of 491 students in Kerala — published as Youth and Migration Aspiration in Kerala, 2022 — “Two out of three youths aspire to migrate abroad in the future for a job and related activities.”

“In the case of Kerala, migration will continue as a potential life choice for achieving life goals for youth in Kerala,” the study’s conclusion read. The reasons for migration of students from Kerala range from the better quality of life and education to the political climate prevailing in India.

Angel Francis, and Meera TP, two nursing graduates working as staffers in a Kochi hospital, are all set to migrate to Ireland for “better lives” this year. Both were classmates in a Karnataka nursing college but have different reasons for their migration, apart from the financial angle.

Angel is the eldest of three siblings from a lower middle-class background, and has the responsibility of her entire family and she was finding it hard to manage with her present salary. “I have been working for the last six years with a starting salary of Rs 13,000. We had this foreign opportunity in 2020, but could not travel because of the Covid pandemic. For me this is a life-saver, otherwise, I don’t know how my family would have survived,” Angel said.

Meera, who has already lost both her parents, on the other hand, comes from an ‘aristocratic’ family, now controlled by her uncles. She has opted to leave the country to be able to exercise her choices. “Of course, salary matters. It’s hard to work here at this meagre income. But my real issue is that I am not in a good relationship with my family and I have a relationship with someone from outside our community. I cannot live with him peacefully here, so we have decided to migrate at the first available opportunity,” Meera told The Federal.

Her boyfriend, who is a radiologist, is also trying to get a job in Ireland. “If he cannot find a job soon enough, we will get officially married so that I can take him as my spouse. Most probably, I won’t be coming back or settling here in Kerala. I have a house in my name in Trissur, which I would probably sell off, once we are settled abroad,” she shared.

“I migrated to Canada not only because of the educational and job prospects, but living in India in the present political circumstances is pretty tough, especially for people like me, Bina, a student who identifies herself as queer, told The Federal from British Columbia, over phone.

This is not a phenomenon exclusive for Kerala, by far. These testimonials should be read along with the data provided in Parliament. A total of 2,25,620 Indians renounced their citizenship in 2022, the highest in the past 12 years, and more than 1.66 million people have given up their nationality since 2011.

“Houses will be for sale on a large scale – many children are in fact waiting for the parents to die to sell the houses. This will cause a huge outward remittance. We always talk about inward remittance and its impact on our economy, but we never have discussed about outward remittance. Crores of rupees are going from Kerala as student fees,” Irudayarajan said.

Irudayarajan thinks the introduction of new tax will expedite this trend. “This trend will result in the collapse of housing real estate. People will stop buying houses in Kerala as investment. Keralites may go to other states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka and buy houses. Or else the investment will shift to gold. Given that a strong gold racket is already in play, this could be a game changer causing long lasting impact on the Kerala’s economy’ warns the migration expert.

The introduction of tax for vacant houses has not gone well with many expats, especially those who live in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Many want to return to their hometown houses once they retire from their jobs. “The government is exploiting those it claims are the backbone of India’s economy. Most of us build houses in hometowns to come back and spend the fag end of our lives, with our loved ones and taxing that is un ethical,” said Sulfikkar Marakkar of Chavakkad, who has been working in the construction sector in the UAE since the last three decades.

On the other hand, there are people who believe that the government’s decision is justified, considering these additional houses are staycation homes which come under the category of service industry and should be taxed accordingly.

The decision to levy a tax on additional houses has triggered yet another round of discussion on migration from the state and its impact on the state’s economy.

(Some names and locations have been changed to protect identities)