- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

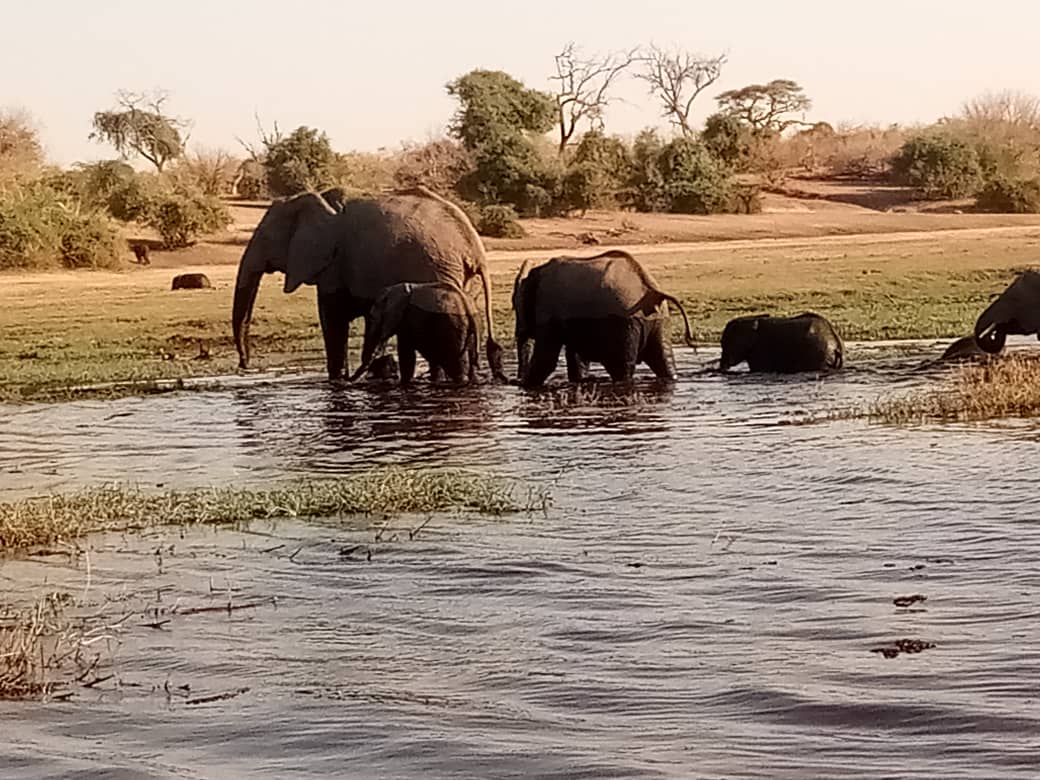

Mysterious elephant deaths in Coimbatore: A Botswana in the making?

Following reports about the mass elephant deaths in Botswana, conservationists in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore are worried if a similar bacteria is causing elephant deaths here.

In May and June this year, one after another more than 350 elephants dropped dead in the Okavango Delta in Botswana, a small landlocked country bordering South Africa. If that wasn’t shocking enough, the fact that some of them appeared to have collapsed to death all of a sudden while “walking or running” added to the mystery behind the mass deaths. Also, all the bodies had their...

In May and June this year, one after another more than 350 elephants dropped dead in the Okavango Delta in Botswana, a small landlocked country bordering South Africa. If that wasn’t shocking enough, the fact that some of them appeared to have collapsed to death all of a sudden while “walking or running” added to the mystery behind the mass deaths.

Also, all the bodies had their tusks intact and had no bullet holes ruling out the involvement of ivory poachers.

There was almost nothing that could explain the possible reason behind the flummoxing deaths even as carcasses were found clustered around waterholes. Some of them appeared to have died “falling flat on their faces,” news reports from the time quoted Niall McCann, director of conservation at United Kingdom charity National Park Rescue, as saying.

About three months later, on September 21, officials revealed the reason behind the mysterious deaths — a kind of bacteria called cyanobacteria found in contaminated water.

Following reports about the Botswana incident, conservationists in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore are worried what if a similar bacteria is causing elephant deaths here.

As many as 19 elephants have died in Coimbatore forest division alone, out of the total 64 across the state, since January this year.

The Asian elephants and its subspecies — Indian, Sri Lankan and Sumatran — are considered endangered animals. Based on the data from 2017 Synchronised Elephant Population Estimation, as many as 27,312 elephants are found in India. In Tamil Nadu, the number is 2,761. This is a sharp fall from the 2012 census numbers — 4,015.

According to the state forest department data, every year, elephant deaths have been increasing. It was 61 in 2016, 78 in 2017, 84 in 2018 and 108 in 2019.

Deepak Nambiar, founder-trustee of Elephas Maximus Indicus Trust, feels the natural water resources in the Coimbatore forest range must be tested for toxins or any infections.

“Due to the increasing number of elephants in smaller areas, they are forced to share limited resources. Overcrowding can lead to contamination of water resources and increased occurrences of parasitic diseases,” he says.

Another possibility, Nambiar adds, could be that the elephants consumed water or fodder laced with chemical pesticides from nearby farms.

“Besides, the forest department should also check for diseases like anthrax, elephant pox, herpesvirus, trunk paralysis and tuberculosis that may become a reason for elephant deaths.”

Hotspot for human-elephant conflict

The Coimbatore forest division has an area of 694 sq km and is located in the southeast of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve (NBR). The division has six forest ranges namely Coimbatore, Boluvampatti, PN Palayam, Karamadai, Mettupalayam and Sirumugai. Of the 19 deaths in the division, about eight occurred in Sirumugai forest range. And in this division alone, 10-12 elephants are dying every year.

According to a paper published in 2014 by elephant expert B Ramakrishnan, the Coimbatore forest division is one of the hotspots for human-elephant conflicts with a sizable elephant population. Based on a 2017 estimate, the division has a total of 97 elephants.

It is also a viable habitat for resident and migratory elephants. More than 20% of the area of the reserve forest serves as a viable corridor for the movement of elephants between Silent Valley National Park and the Eastern Ghats and vice versa, says the paper.

“The movement of elephants in Coimbatore forest division is mostly restricted to the foothills due to the escarpment of steep slopes on the west and human habitations on the east. Therefore, human-elephant conflict is higher compared to other largely populated elephant habitats in South India,” says Ramakrishnan, who is also a member of International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Asian Elephants Specialists Group.

Since Coimbatore forest division shares a 350-km-long boundary on the east with human habitations and farm lands, the villages adjoining the reserve are highly prone to elephant depredation.

“Earlier elephants used to visit only the fringe villages, attracted by standing crops. These days however, elephants are coming frequently into the human habitation and crop fields located even more than 5 km from the forest boundary. The elephant movements in this division are mostly restricted to very narrow paths of the foothills of the large mountains naturally near the human habitations,” he says.

One reason for this could be that the Coimbatore and Hosur forest divisions have seen huge changes in land use pattern. Once forested areas have become revenue lands in the last two decades and have been diverted for agricultural usage and construction of buildings. “So these areas are highly prone to human-elephant conflicts,” says N Baskaran, assistant professor, Department of Zoology and Wildlife Biology, AVC College, Myladuthurai district.

Also, he adds, one cannot say for sure that the elephants which died lived only in Coimbatore. “Elephants tend to move to areas which have recently received rains because those areas have fresh grass. The migration coincides with cultivation and there are possibilities for conflict. We must check what the farmers did that led the elephants towards slow death,” he says.

Diseases a major concern

Elephant deaths are mostly reported due to train accidents, falling from slopes, electrocution, diseases and natural causes like fighting with other elephants. Apart from these reasons, experts are unable to arrive at any other concrete answers. Hence, classified as unknown deaths.

However, according to Ramakrishnan’s paper, elephant deaths between 1999 and 2014 were mostly caused by diseases. Out of 133 elephant deaths, 50 occurred due to diseases. The Sirumugai forest range had a high proportion of deaths at 24%.

“The Pethikuttai forest beat in Sirumugai forest range is the place where eight elephants died,” says K Kalidasan of environmental NGO Osai.

“The 2,080 hectare forest patch is situated near Bhavani Sagar reservoir. Elephants used to graze in the forests and come to the reservoir to drink water and return. But during that time, due to heavy rains, the water level in the reservoir increased and flooded the area. So, the elephant herd was pushed to stay in the forest for months together.”

The 19 deceased elephants — taking together all elephants male, female as well as makna (tuskless elephants) and across all ages — died due to various reasons like gunshots, in-fighting between elephants, pregnancy risks, falling from slopes, electrocution, old age and diseases.

K Kalidasan feels there isn’t much need for panic as this is not a sudden phenomenon but also cautions that a large number of elephant deaths happening in a particular area is indeed a reason to cause alarm.

In 2016, 22 elephants died and in 2018, 18 deaths were recorded, he tells The Federal.

“Elephants need grass. That’s their preferred staple food. But in Pethikuttai, the forest is largely filled with the invasive plant Prosopis juliflora and that affects the growth of grass. It is possible that the elephants [which died from diseases] may have died due to the lack of nutritious food,” he adds.

But despite serious concerns raised by conservationists and activists, district forest officer D Venkatesh feels comparing the mass elephant deaths in Botswana and those in Coimbatore is far-fetched.

‘No similarity with Botswana’

“In Botswana, the elephants died at the same time and in the same manner. But in Coimbatore, the deaths are spread over nine months and the reasons are varied. Only four elephants were suspected to have died from disease because they had liver cirrhosis. We need to find what caused that problem,” he says.

A seven-member expert committee was formed in July to study the deaths but the process has been stalled due to COVID-19.

Rejecting allegations that the forest department has not made the necropsy reports public, Venkatesh says that there are some protocols to be followed.

“We do post-mortem in the presence of three NGOs and two veterinarians. We report wildlife deaths to the media. With prior notice, anybody can visit the office and look for data. We try to ensure larger transparency,” he says.