- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Mission Hayabusa: What a Japanese hunt for asteroids reveals about Earth's origin

On December 6, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA, added another feather to its cap by achieving a magnificent space feat. JAXA’s robotic spacecraft Hayabusa 2 travelled to a near-earth asteroid called Ryugu, dug into its soil, retrieved the sample and returned with it to earth. A specially designed 16-kilo capsule on Hayabusa 2 encapsulated the soil samples and later dropped...

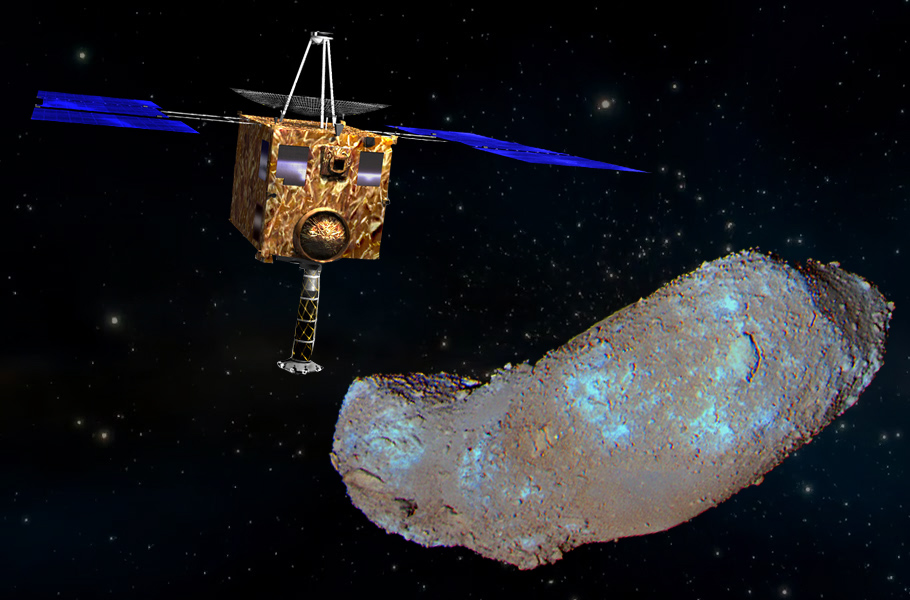

On December 6, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA, added another feather to its cap by achieving a magnificent space feat. JAXA’s robotic spacecraft Hayabusa 2 travelled to a near-earth asteroid called Ryugu, dug into its soil, retrieved the sample and returned with it to earth.

A specially designed 16-kilo capsule on Hayabusa 2 encapsulated the soil samples and later dropped it down in the Australian outback of Woomera. It was quickly retrieved by experts who carefully transported it to the Japanese agency.

JAXA is a pioneer in such ‘sample return missions,’ holding the world record for being the first to send robotic probes to asteroids and bring back samples successfully.

Hayabusa 2 is JAXA’s second such mission and a successor of its first mission the Hayabusa sent to another asteroid about a decade and a half ago.

Why explore asteroids?

For about 140 million kilometres between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, chunks of irregularly shaped rocks roam around in space. These space rocks or asteroids vary from pebble size to several hundred kilometres across, and there are millions of them, giving the region the name of the asteroid belt.

In the early days, when the solar system was being born, the nebula that created it was a raging, roiling mass, spewing hot gases and rocky debris into space.

The asteroids are leftover bits of rocky masses from this period. Some of the space rocks coalesced to form planets. Some smaller objects were pulled into the gravitational tug of the planets and became their moons.

However, when Jupiter was formed, its massive gravitational grip prevented further rocky masses from coalescing. Asteroids are the remnants of these space rocks which circle the sun.

Asteroids garnered attention when astronomers found that their composition had not undergone much change after more than 4 billion years. So, their soil contains elements and minerals in their pristine form from the formative days.

Asteroids are mostly rock and dust without an atmosphere. However, they have rich metallic deposits such as iron, titanium or platinum. Some asteroids also contain ice water.

Scientists believe that when the earth was forming, asteroids crashed into it, carrying with them rich mineral deposits, water, and carbon-based molecules.

Hence, it is believed that analysing asteroid soil samples will reveal the source of several terrestrial elements, and give clues of how life began on earth.

The Hayabusa missions set out on this quest to explore two near-earth asteroids and bring back soil samples for scrutiny.

The Hayabusa

Japan’s Hayabusa mission was one of the most iconic space ventures that demonstrated the technical capability to travel to an asteroid, scrape the surface soil, and return successfully with it. The Japanese space agency is the first in the world in achieving sample return missions, meeting all the technical challenges of the feat.

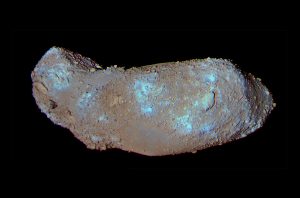

In 2003, Japan launched the 500- kilo Hayabusa spacecraft on a seven-year-long mission in search of a peanut-shaped asteroid (the S-type asteroid) called 25143 Itokawa. Hayabusa rendezvoused with its target in 2005 and then hovered around it, studying its surface details.

Itokawa is a rubble pile of porous and low-density boulders and soil. In November 2005, the Hayabusa successfully touched down on the surface of the asteroid and released a small rover called MINERVA.

For the next two years, the rover took scientific measurements of Itokawa scouring along the 100 feet long space rock. During its tenure, Hayabusa collected 1,500 dust particles (less than one gram of the regolith dust) from a smooth region on the asteroid. The mineral-dense sample was encapsulated in a 40-centimetre container.

The Hayabusa wrapped up its mission in 2007 and embarked on the return journey, reaching earth by 2010. It successfully dropped the container on the ground, after which as per space protocol, the spacecraft burned away in the earth’s atmosphere.

JAXA shared five particles from the sample to cosmo-chemists Ziliang Jin and Maitreyee Bose at the Arizona State University, who conducted detailed assessments on them.

Itokawa is known to have had a history of multiple impacts, fragmentation, and exposure to intense radiations. What remains presently is the remnant of a much larger similar parent body that was at least ten times bigger. It is known to be a dry asteroid.

However, when the team applied advanced sensitive analysis of the samples, they were surprised to find that the soil samples were enriched with water.

The mineral assessment showed that Itokawa contained hydrogen isotopes similar to those found on earth. In two out of five particles, they identified a mineral called pyroxene. On earth, pyroxene traps water molecules, and the samples similarly held water in them.

The team published their findings in the journal Science Advances in 2019. In their report, they state that although the parent rock broke into bits, the samples retained the water in them without losing it in space.

They conjectured that such parent asteroids impacted the earth in its formative stages, delivering almost half of the water in our oceans.

Hayabusa 2

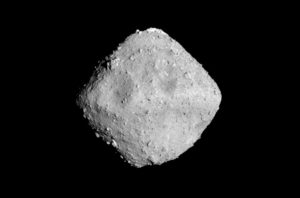

The success of the first mission prompted JAXA to invest in another mission. In 2014, the Hayabusa 2 targeted 162173 Ryugu, a diamond-shaped space rock (C-shaped asteroid). Highly advanced instruments and navigation systems accompanied the spacecraft, hurling it into space in the quest of the 900-metre, crater-filled asteroid.

The rubble of carbonaceous rocks on the asteroid is believed to be older than 4.6 billion years and considered to contain primordial life material.

The Hayabusa reached Ryugu in 2018, and hovered over the asteroid at a distance of 20 km for 16 months. In early 2019, it shot a small high impact cannonball on to the asteroid’s surface, creating a little artificial crater.

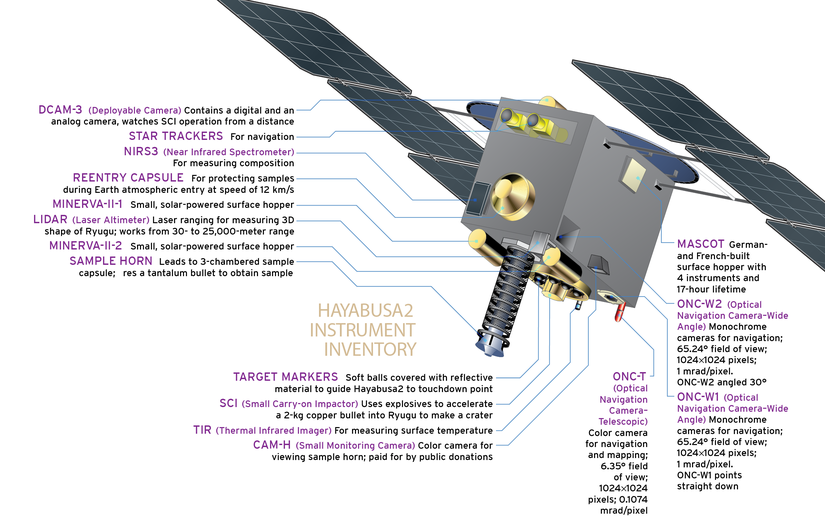

Then, the Hayabusa 2 dropped two hopping robots MINERVA II 1A and MINERVA II 2B, and another robot MASCOT from Germany.

While the robots conducted scientific studies, the Hayabusa dropped an impactor probe from a 9-m height at the impact region to collect the soil samples. These samples were successfully returned to earth on December 6.

JAXA will be sharing tiny amounts of the soil with NASA. A global team of astrobiologists will employ advanced assessment methods on the contents. The teams will screen the soil particles for traces of organic compounds, identify, and separate them.

Nasa scientists consider the assessment a huge challenge given the minute size of the samples. However, they opine the analysis could indicate if, like water, the life-signatures too were brought to earth from outer space by asteroids.

What these grains of sands reveal may rewrite the story of our origins.