- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

In Karnataka, a model for social media smear

It’s 2.30 in the afternoon on April 4. A political rally by Karnataka Chief Minister’s son Nikhil Kumaraswamy is about to take place in Mandya’s Thimmakoppalu, a village about 120 km from the state capital. Sitting outside the house with his grandmother and a dog in tow, 22-year-old Abhishek TD, a farmer’s son, browses videos on his smartphone. He’s politically active on social...

It’s 2.30 in the afternoon on April 4. A political rally by Karnataka Chief Minister’s son Nikhil Kumaraswamy is about to take place in Mandya’s Thimmakoppalu, a village about 120 km from the state capital.

Sitting outside the house with his grandmother and a dog in tow, 22-year-old Abhishek TD, a farmer’s son, browses videos on his smartphone. He’s politically active on social media platforms, but shows no interest in Nikhil’s rally. Even as Nikhil’s election caravan passes his street, his eyes remain hooked to his smartphone where troll videos of the young politician stream.

While the entire state watches the Mandya Lok Sabha constituency in anticipation, where the Janata Dal (Secular) candidate Nikhil contests against independent candidate Sumalatha Ambareesh, it’s a done deal for Abhishek. He has made up his mind on who to vote for. In fact, his support to actor Sumalatha is so strong that his WhatsApp profile picture is one that seeks votes for her.

Ask him why and he says it’s simple, showing a couple of memes that mock Nikhil. “Everybody makes fun of him (Nikhil) and trolls him. Why would I vote for a…joker?” he asks with a laugh. Abhishek consumes mobile data to watch videos on YouTube, TikTok and WhatsApp in his free time.

Nikhil became the subject of ridicule during the audio launch of his movie Jaguar in 2016. At the launch, now Chief Minister Kumaraswamy’s effort to popularise his son went viral among YouTubers and meme creators. Kumaraswamy calls for his son, “Nikhil yellidiyappa? (Nikhil, where are you?)”, and Nikhil emerges from the crowd to say he’s among the people.

People viewed, recreated and shared the clip among their closed circles to mock Nikhil’s absence in politics until now. Ever since he was announced as the JD(S) candidate for Mandya, about 362 such videos have popped up to gain 11.8 million views (on YouTube alone) — about seven times the voter population in Mandya, according to The Federal analysis.

Anyone on the move in Mandya — be it the working class, college students, tech-enabled farmers, or women labourers who take a break to watch television at home — are quick to talk about ‘Nikhil Yellidiyappa’ videos and memes. Even regional news channels populated news and programmes with this. Students trolled him in college cultural events.

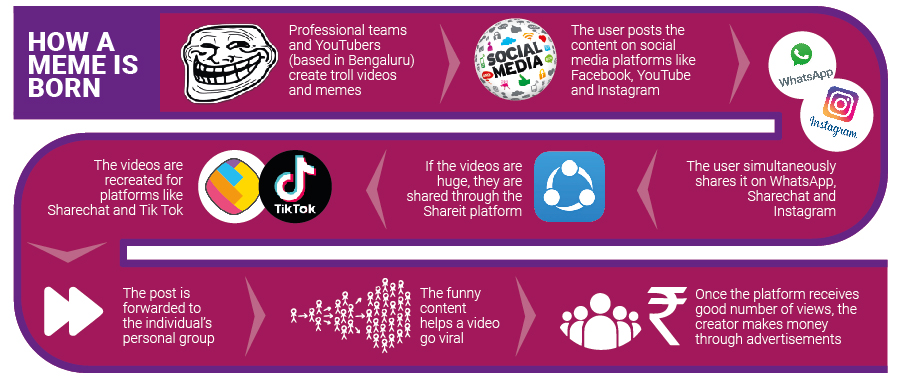

In Abhishek’s case, the videos constantly played for the past month, shaping his views on the candidate. He further influenced others in his friends circle by debating on the subject. Professional teams, some sitting in Bengaluru, create these videos and memes, to gain more viewers on their platform. They first post on social sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, and then spread them on WhatsApp. Viewers recreate these on new-age platforms like ShareChat and TikTok and share it to entertain or further influence fellow voters. Though political intent can be ruled out in this case, smear campaigns by certain individuals certainly play a large role in the voting preference of people.

‘The Screwless Brain’, a professional meme creator who runs Troll Anthammas, a digital marketing and content marketing platform, is one of the largest troll video producers. The account runs memes and YouTube videos on Kannada movies, cricket and politics.

The administrator of the platform, a 25-year-old engineering graduate from Sirsi, says that there was no political intent behind creating videos titled ‘Nikhil Yellidiyappa.’ “We make videos that are fun to our viewers. Unfortunately, our viewers keep asking for more videos on that topic and that’s why we made so many such videos. We do not want to get into a political war,” said the person, not wanting to reveal their identity.

Other popular meme creators on this topic include — Always be Viral, Kannada Memer, Cmpunekar CMP (account blocked due to copyright infringement), and Kannada Cinema Star. Most of these accounts create videos and memes based on famous Kannada movie dialogues. Most of these account holders, when contacted through Facebook, declined to comment for the story.

In India, Rahul; in Mandya, Nikhil

In this day and age, it’s impossible to scroll through social media platforms and not see something political. Political parties actively engage these platforms to spread customised content — some to provide information, some to mock the opposition candidate, or spread snippets of speeches of party leaders.

Memes help political parties reach young adults and engage them politically so as to shift the political discourse in a party’s favour. For 18-year-old Maya Singh in Patna, Facebook is the central source of political information. With different kind of posts available on the platform, Singh believes he can make an informed decision as a first-time voter this Lok Sabha election.

Singh frequently receives positive memes on Bharatiya Janata Party and PM Modi on platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook, while he receives negative memes on Congress president Rahul Gandhi. He doesn’t mind seeing political ads while scrolling through his Facebook or Instagram pages. He is one among the many target audience for the social media campaigns run by mainstream political parties.

During the 2016 US Presidential election, Donald Trump’s controversial statements and his style of politics against his opponent Hillary Clinton were gold for meme makers. This site shows how memes spread ahead of the elections.

While no political intent was established in Nikhil’s instance, nationally, leading political parties, particularly the ruling BJP, resort to smear campaigns against the opposition. A recent report by The Huffington Post indicated how the BJP turned a women’s NGO into a secret propaganda machine. Earlier in 2016, Delhi-based journalist Swati Chaturvedi, in her book ‘I Am a Troll’, alleged that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s campaign in 2014 used hundreds of social media volunteers to push critical and abusive messages against people who opposed the BJP.

Driven by the smartphone revolution, and a digital population of 462 million users, India has 300 million Facebook users — the highest in the world. The user base tripled since the last general election, according to data platform Statista. With social media wielding some influence on voters, India’s 17th general election — to be held in seven phases in April and May — will see a close contest.

While the BJP, which supports Sumalatha’s candidature, categorically denied any involvement in spreading these memes and videos against Nikhil, it did say that pumping in information multiple times might change the voters’ perception. “Social content might not change a voter’s mind in a day. But if we feed the information multiple times, it helps us create a certain perception based on the set narrative,” S Bajaji, convenor of BJP’s social media cell in Karnataka told The Federal. Sumalatha’s husband and late actor-turned-politician MH Ambareesh was with the Congress and she expected to run for the party before it ceded the seat to its coalition partner JD(S). This forced Sumalatha to contest as an independent candidate and many, including Congress workers and the BJP, have backed her.

Psephologists beg to differ

Psephologist Sandeep Shastry argues that there was no empirical evidence (in India) to show that people’s voting preference changed because of social media content. “Social media may not alter the voters’ perception, but it strengthens their existing beliefs. People will like and share not because something is informative, but because it may appeal to their mindset and thinking,” Shastry explained.

A 2017 study by Amity School of Communications reveals that internet memes are used as a tool for communicating political satire but do not have an impact on the audience. So, do candidates who are mocked take such content seriously? Does Nikhil worry at all?

In an interview to a regional channel, he said, “We should take it in a sportive manner. Otherwise it would be difficult for us to play politics. It doesn’t take much time for us to create such memes and ask BJP Yellidiyappa (considering they are barely present in Mandya).”