- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Living with rare diseases: Five families, one shared hope

Both the Centre and states do not have a policy to support the treatment for rare diseases and India has no budget for rare diseases.

Sini Mujeeb was like any other college student—young, gregarious and full of dreams. It wasn’t until her early days in college that she realised something was wrong with her leg muscles. She would often lose balance and trip, leaving her with unexplained bruises. It took two years for doctors to finally diagnose her condition—muscular dystrophy. Twenty four years on, Sini, now a...

Sini Mujeeb was like any other college student—young, gregarious and full of dreams. It wasn’t until her early days in college that she realised something was wrong with her leg muscles. She would often lose balance and trip, leaving her with unexplained bruises. It took two years for doctors to finally diagnose her condition—muscular dystrophy. Twenty four years on, Sini, now a school teacher in Kerala’s Alappuzha, has been living in a wheelchair.

“I was like any other child till the age of 18. Initially, I had difficulty walking. The muscles in my body would stiffen. Gradually, I started feeling acute pain all over my body. Soon, there was no strength left in my body muscles and I had to depend on others even for simple things,” she says.

Sini’s condition—muscular dystrophy is a rare disorder—that causes progressive weakness and muscle degeneration. In most cases, it runs in the family. It usually develops after inheriting a faulty gene from one or both parents.

Experts say while there are many kinds of muscular dystrophy, signs of the most common variety begin to show in childhood, mostly in boys. Other types, like in Sini’s case, don’t surface until adulthood.

Even though there is no definite cure for muscular dystrophy, medications and therapy do help manage the symptoms and also slow the course of the disease.

The battle ahead wasn’t easy by any means for Sini. “Initially I was given ‘wrong medicines’ for the symptoms which worsened my condition. But I had decided, I wasn’t going to give up without a fight.” Despite having acute body pain and movement difficulties, Sini completed her graduation and teacher’s training course.

Today, Sini is not just a dedicated teacher but also a motivational speaker. She often divides her time to work with people suffering from similar conditions.

Supporting each other

Like Sini, 34-year-old Krishna Kumar of Thiruvananthapuram, has also made it his life’s mission to make people aware of rare diseases and how to cope with them. Krishna was just nine months old when he was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy (type 2). His condition worsened following a road accident in 2011 in which he lost his sister. “She was younger than me and had the same disease,” he recollects.

But unlike Sini, Krishna never had the opportunity to get formal education. “I was homeschooled but was fortunate to have access to a lot of books. My father’s a voracious reader. When I look back, I don’t feel disappointed for not getting the opportunity to go to school like other children. Rather, I think I gained from it,” says Krishna, who is a frequent visitor to schools and colleges to talk to children and run awareness programmes.

He also happens to be the President of MIND (Movement in Dystrophy), an organisation for people suffering from SMA and Muscular Dystrophy.

“We have around 600 members now. As a collective, we have been successful in helping our members get benefits from the government.” His organisation has a list of demands for the government, ranging from financial support to the rehabilitation for the victims of rare diseases.

“We need to have a comprehensive approach. Each person living with SMA or muscular dystrophy or any other rare disease has specific needs. Governments should have a policy to address the same,” he says.

Krishna was reminded of his own struggles as a child when he read about one-and-a-half-year-old Muhammed, who also suffers from SMA. The toddler from Kannur in Kerala was recently in news when his parents, Rafeeq and Mariyumma, successfully raised Rs 18 crore through crowdfunding in a week’s time.

The money will be used to procure a single-dose drug, Zolgensma (the world’s most expensive drug), that has to be imported from the US. One dose of the drug costs Rs 18 crore, something far beyond the reach of Rafeeq and Mariyumma.

But their prayers were answered and the doctors at Baby Memorial Hospital in Kozhikode have started the procedure to procure the medicine.

There are, however, many such children and their parents who are expecting a similar miracle to happen. Muhammed is not the only baby in his family suffering from this disease. His sister Afra is one of them. Sadly, doctors say, the 15-year-old girl doesn’t have as good a chance as Muhammed. But Afra is very happy for her little brother. A video in which little Afra is seen requesting people to come to her brother’s support is one of the many such clips that has gone viral and helped raise the money.

Looking at the love and solidarity extended to Muhammed, Ishal Mariyam’s parents too have made a public appeal on social media seeking support for their 90-day-old baby. Ishal, the only child of Lakshadweep-based couple Nasar and Jaseera, has been diagnosed with the same rare disease, SMA. PP Muhammad Faizal, a member of Parliament from Lakshadweep, too has lent his support and released a video requesting support for Ishal.

But crowdfunding is not a permanent solution. “Even though it might work for one or two, there is a need for intervention and strategic planning from both Central and state governments. Unfortunately, there is nothing in place as of now. We do not even have enough laboratories in the country to diagnose the disease to begin with,” says Dr Mohandas Nair of Government Medical College, Kozhikode.

Govt support crucial

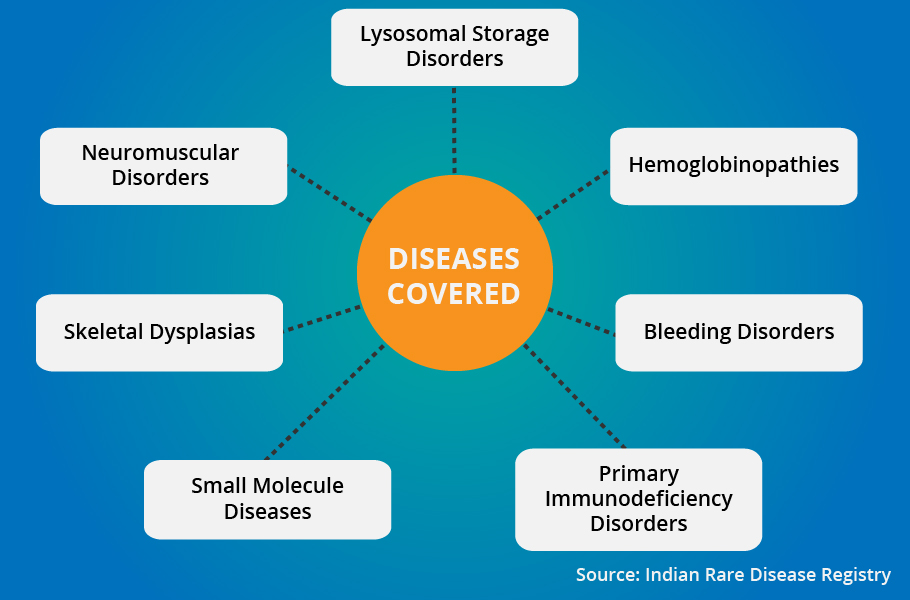

There are many others who share Dr Mohandas’s concerns. India is yet to have a national registry of rare diseases. In 2017, such a registry was launched but it is still in the works. In other words, the country does not know how many people have been suffering from rare diseases like spinal muscular atrophy.

According to the National Policy for Rare Diseases, 2021, issued by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, a consensus is yet to be reached on how to define a rare disease. There is no adequate research as well.

According to the policy document, “Apart from a few rare diseases, where significant progress has been made, it is still at a nascent stage. For a long time, doctors, researchers and policy makers were unaware of rare diseases and until very recently there was no real research or public health policy concerning issues related to the field. This poses formidable challenges in development of a comprehensive policy on rare diseases.”

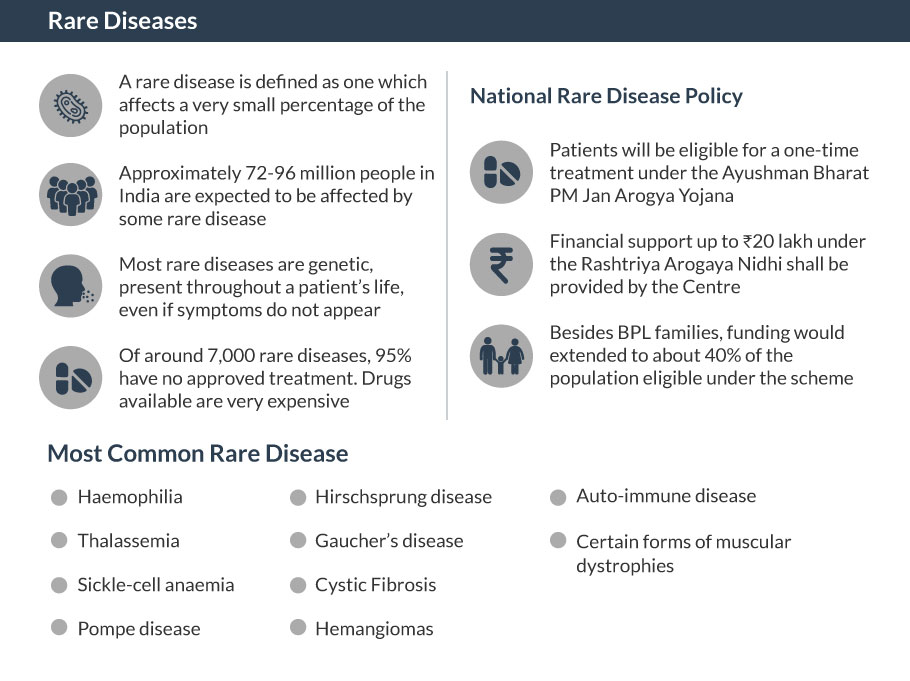

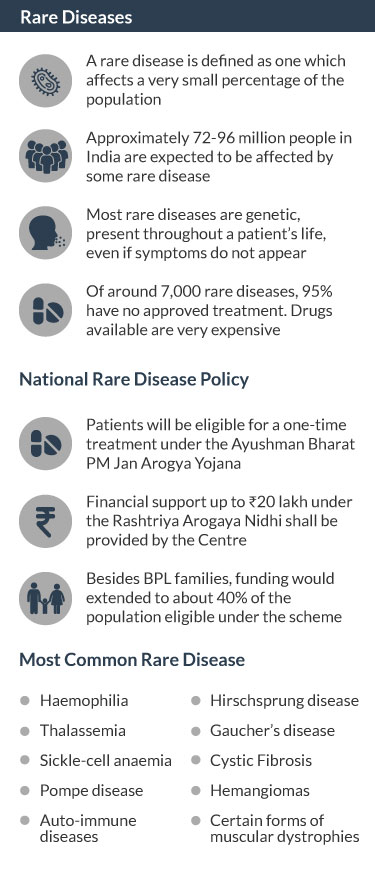

The definition of rarity, according to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, varies from country to country. The World Health Organization defines rare disease as often debilitating lifelong disease or disorder with a prevalence of 1 or less, per 1,000 population. Different countries have different parameters. In the US, rare diseases are defined as a disease or condition that affects fewer than 200,000 patients in the country (6.4 in 10,000 people). EU defines rare diseases as a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people. Japan identifies rare diseases as diseases with fewer than 50,000 prevalent cases (0.04%) in the country. According to the Indian Rare Disease Registry website, a disease or disorder is defined as rare in India when it affects fewer than 1 in 2,500 individuals.

However, according to the national policy for rare diseases, the government does not agree with the idea of measuring rarity only on the basis of prevalence. “Rare diseases are difficult to research upon as the patient pool is very small and it often results in inadequate clinical experience. Therefore, the clinical explanation of rare diseases may be skewed or partial. The challenge becomes even greater as rare diseases are chronic in nature, where long-term follow-up is particularly important. As a result, rare diseases lack published data on long-term treatment outcomes and are often incompletely characterised,” states the National Policy for Rare Diseases, 2021.

In absence of a clear definition, it is apparent there is no data on the people suffering from rare diseases. “Data on how many people suffer from different diseases that are considered rare globally, is lacking in India… In such a scenario, the economic burden of most rare diseases is unknown and cannot be adequately estimated from the existing data sets,” states another paragraph from the policy document.

However, approximately 72 to 96 million people in India can be expected to be affected by some form of rare disease.

Others working in the field have also managed to collect some data, though not comprehensive.

“There are 112 SMA patients in Kerala. As of now, we know 48 in Tamil Nadu, 28 in Karnataka and 50 in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana,” says Dr Razeena, President of cureSMA Foundation of India , the collective of the family members of patients suffering from Spinal Muscular Atrophy.

Razeena’s only son, 15-year-old Rahan also suffers from the same condition. Her organisation has managed to count a total 552 SMA patients in India. “This data is not comprehensive, this is the number of patients that we know. The actual number could be much bigger,” says Razeena.

It is believed while half of rare diseases appear in children, one-third die before they turn five. Only 5 percent of such diseases have a cure. But with proper medication, patients can have a better and longer life. And that’s where the problem begins since most of the medication for rare diseases are exorbitantly expensive. Also, not a single one is manufactured in India.

What’s more, both the Centre and states do not have a policy to support the treatment for rare diseases. Sadly, while India has no budget for rare diseases, health insurance companies do not cover them.

Why is the treatment so expensive?

As the number of persons suffering from individual rare diseases is small, they do not constitute a significant market for drug manufacturers to develop and bring to market drugs for them. It is for this reason that these diseases are also called ‘orphan diseases’ and the drugs ‘orphan drugs’.

“The pharmaceutical companies recoup the expense of the research and development of such drugs by imposing high prices. They cannot go for mass production of such orphan drugs. The only solution is to have an international policy formulated by organisations like WHO. The governments also need to shape up such policies to enhance research and development of drugs,” says Dr KP Aravindan, former professor at Government Medical College, Kozhikode.

According to him, India is a country that has the potential to create knowledge in the field of gene therapy. “We are capable of developing research and producing such drugs, it is a matter of priority.”

Experts say there is another reason why Indian pharmaceutical giants don’t feel motivated enough to make drugs for rare diseases available. To encourage the development of drugs for rare diseases, countries such as the US provide economic incentives to pharmaceutical companies under the Orphan Drug Act. There is no such provision in India.

So, patients and their families are left to fend for themselves, most often than not depending on preventive care and awareness. But this too rests with the state governments.

Preventive care and awareness

While prevention and awareness play a better role than cure, it requires enormous funds. “Majority of the people don’t know anything about rare genetic disorders. There is an urgent need to launch awareness campaigns,” says Dr Mohandas.

According to him, 50 per cent risk could be reduced by avoiding marriages within extended families or within the same descent, caste etc. This is something that raises vulnerability to genetic disorders.

“Studies in countries like the US indicate that there is a high prevalence among closed communities in which people marry within closed family circles. Hence, there is a need to carry out awareness campaigns to avoid such marriages as best as possible.”

There is a need to do targeted screening as well. “Most couples who have one child with a rare disease go for a second one without any medical surveillance. This increases the risk of having more babies with rare genetic diseases,” he adds.

This is indeed true in the case of Rafeek and Mariyumma. Even after Afra was diagnosed with SMA, neither Rafeeq nor Mariyumma had a clue about the need for prenatal tests while going for another child. “Nobody told us anything like that. When Afra was young, we did not even know anything about this,” says Rafeeq.

They have three kids and the second child, seven-year-old Anzila, is healthy so far. Muhammed is the third child of Rafeeq and Mariyumma. According to Dr Mohan Kumar, it’s difficult to expect ordinary people to go for prenatal tests even if they have a child with a rare disease. “The chances of having a baby with the disease is only 25 per cent for the carrier couple. The carrier parents may have one child with the disease and they may have the second child free from the disease. It is a matter of chance.” Even highly educated people, he adds, don’t know about such diseases.

To add to all, there is the cost factor. “Prenatal tests are pretty expensive. It normally costs around Rs 30,000 to 40,000 in the private sector,” says Dr Mohandas.

However, according to the policy for rare diseases issued by the Centre, “Public health and hospitals being a state subject, the central government shall encourage and support state governments in implementation of a targeted preventive strategy.”

It further states that “state governments may undertake treatment of disorders managed with special dietary formulae or food for special medical purposes and disorders that are amenable to other forms of therapy (hormone/ specific drugs)”.

But people like Dr Aravindan aren’t convinced. “No state government can handle the financial burden of supporting people with rare diseases all by itself. The central government has to play a proactive role, instead of putting the entire responsibility on the shoulders of the states.”

The centre though has proposed a scheme of providing financial aid up to 20 lakh under the Rashtriya Arogya Nidhi. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is also pinning hopes on the benevolence of individuals and corporations. “Keeping in view the resource constraints…the government will endeavour to create an alternative funding mechanism by setting up a digital platform for voluntary individual and corporate donors to contribute to the treatment cost of patients of rare diseases.”

But how far can patients and their families depend on the benevolence of individuals?

Dr Razeena is very clear that this is not a sustainable model. “What we want is intervention from the government. Research, drug manufacturing, financial packages and insurance coverage to the victims of rare diseases are some of the niche areas. To begin with, we need to have a national registry of rare diseases.”

But till the time that happens, Sini is determined to do her bit. “When I was first diagnosed, I decided I’ll give my best fight and not slip into depression.” Sini wants to give the same courage to others fighting rare diseases. It was this faith that perhaps has kept her going. Of course, her husband, too, has been a great strength to her. Mujeeb Rahman was her batchmate in college.

“We were friends for a long time. After my father passed away in 2001, he proposed to me. Initially, both the families were a little reluctant because of my disease. But he was quite determined.” Sini and Mujeeb now have a daughter, Athila Fathima, studying in class 6.

Sini feels her story could be the story of every other child fighting with a rare disease. “I am happy to share my story if it helps motivate someone else.”